She knew that their brother would have tactfully discouraged them from visiting Pemberley during the present crisis and she had no doubt that they would stay away. A murder in the family can provide a frisson of excitement at fashionable dinner parties, but little social credit can be expected from the brutal despatch of an undistinguished captain of the infantry, without money or breeding to render him interesting. Since even the most fastidious among us can rarely escape hearing salacious local gossip, it is as well to enjoy what cannot be avoided, and it was generally known both in London and Derbyshire that Miss Bingley was particularly anxious at this time not to leave the capital. Her pursuit of a widowed peer of great wealth was entering a most hopeful phase. Admittedly without his peerage and his money he would have been regarded as the most boring man in London, but one cannot expect to be called “your grace” without some inconvenience, and the competition for his wealth, title and anything else he cared to bestow was understandably keen. There were a couple of avaricious mamas, long-experienced in the matrimonial stakes, each working assiduously on her daughter’s behalf, and Miss Bingley had no intention of leaving London at such a delicate stage of the competition.

Elizabeth had just finished letters to her family at Longbourn and to her Aunt Gardiner when Darcy arrived with a letter delivered the previous evening by express, which he had only recently opened.

Handing it to her, he said, “Lady Catherine, as expected, has passed on the news to Mr Collins and Charlotte and has enclosed their letters with her own. I cannot suppose that they will give you either pleasure or surprise. I shall be in the business room with John Wooller but hope to see you at luncheon before I set out for Lambton.”

Lady Catherine had written:

My dear Nephew

Your express, as you will have realised, came as a considerable shock but, happily, I can assure you and Elizabeth that I have not succumbed. Even so, I had to call in Dr Everidge who congratulated me on my fortitude. You can be assured that I am as well as can be expected. The death of this unfortunate young man – of whom, of course, I know nothing – will inevitably cause a national sensation which, given the importance of Pemberley, can hardly be avoided. Mr Wickham, whom the police have very properly arrested, seems to have a talent for causing trouble and embarrassment to respectable people and I cannot help feeling that your parents’ indulgence to him in childhood, about which I frequently expressed myself strongly to Lady Anne, has been responsible for many of his later delinquencies. However, I prefer to believe that of this enormity at least he is innocent and, as his disgraceful marriage to your wife’s sister has made him your brother, you will no doubt wish to make yourself responsible for the expense of his defence. Let us hope it does not ruin both you and your sons. You will need a good lawyer. On no account employ someone local; you will get a nonentity who will combine inefficiency with unreasonable expectations in regard to remuneration. I would offer my own Mr Pegworthy, but I require him here. The long-standing boundary dispute with my neighbour, of which I have spoken, is now reaching a critical stage and there has been a lamentable rise in poaching in the last months. I would come myself to give advice – Mr Pegworthy said that were I a man and had taken to the law, I would have been an ornament to the English bar – but I am needed here. If I went to all the people who would benefit from my advice I would never be at home. I suggest you employ a lawyer from the Inner Temple. They are said to be a gentlemanly lot in that Inn. Mention my name and you will be well attended.

I shall convey your news to Mr Collins since it cannot long be concealed. As a clergyman, he will wish to send his usual depressing words of comfort, and I shall enclose his letter with mine but will place an embargo on its length.

I send my sympathy to you and to Mrs Darcy. Do not hesitate to send for me if events should turn ill with this affair and I will brave the autumn mists to be with you.

Elizabeth expected to get nothing of interest from Mr Collins’s letter except the reprehensible pleasure of relishing his unique mixture of pomposity and folly. It was longer than she expected. Despite her proclamation, Lady Catherine de Bourgh had been indulgent about length. He began by stating that he could find no words to express his shock and abhorrence, and then proceeded to find a great number, few of them appropriate and none of them helpful. As with Lydia’s engagement, he ascribed the whole of this dreadful affair to the lack of control over their daughter by Mr and Mrs Bennet, and went on to congratulate himself on having withdrawn an offer of marriage which would have resulted in his being inescapably linked to their disgrace. He went on to prophesy a catalogue of disasters for the afflicted family ranging from the worst – Lady Catherine’s displeasure and their permanent banishment from Rosings – descending to public ignominy, bankruptcy and death. It closed by mentioning that, within a matter of months, his dear Charlotte would be presenting him with their fourth child. The Hunsford parsonage was becoming a little small for his increasing family, but he trusted that Providence, in due time, would provide him with a valuable living and a larger house. Elizabeth reflected that this was a clear appeal, and not the first, to Mr Darcy’s interest and would receive the same response. Providence had so far shown no inclination to help and Darcy certainly would not.

Charlotte’s letter, unsealed, was what Elizabeth had expected, no more than brief and conventional sentences of distress and condolence and the reassurance that the thoughts of both herself and her husband were with the afflicted family. Undoubtedly Mr Collins would have read the letter and nothing warmer or more intimate could be expected. Charlotte Lucas had been Elizabeth’s friend through the years of childhood and young womanhood, the only female except Jane with whom rational conversation had been possible, and Elizabeth still regretted that much of the confidence between them had subsided into general benevolence and a regular but not revealing correspondence. On Darcy’s and her two visits to Lady Catherine since their marriage, a formal visit to the parsonage had been necessary and Elizabeth, unwilling to expose her husband to Mr Collins’s presumptive civilities, had gone alone. She had tried to understand Charlotte’s acceptance of Mr Collins’s offer, made within a day of his proposal to her and her rejection, but it was unlikely that Charlotte had either forgotten or forgiven her friend’s first amazed response to the news.

Elizabeth suspected that on one occasion Charlotte had taken her revenge. Elizabeth had often wondered how Lady Catherine had learned that she and Mr Darcy were likely to become engaged. She had never spoken of his first disastrous proposal to anyone but Jane and had come to the conclusion that it must have been Charlotte who had betrayed her. She recollected that evening when Darcy, with the Bingleys, had first made an appearance in the Meryton Assembly Rooms when Charlotte had somehow suspected that he might be interested in her friend and had warned Elizabeth, in her preference for Wickham, not to slight a man of Darcy’s much greater importance. And then there had been Elizabeth’s visit to the parsonage with Sir William Lucas and his daughter. Charlotte herself had commented on the frequency of the visits of Mr Darcy and Colonel Fitzwilliam during the visitors’ stay and had said that it could only be a compliment to Elizabeth. And then there was the proposal itself. After Darcy had left, Elizabeth had walked alone to try to quieten her confusion and anger but Charlotte, on her return, must have seen that something untoward had happened during her absence.

No, it was impossible for anyone other than Charlotte to have guessed the cause of her distress, and Charlotte, in a moment of conjugal mischief, had passed on her suspicions to Mr Collins. He, of course, would have lost no time in warning Lady Catherine and had probably exaggerated the danger, making suspicion into certainty. His motives were curiously mixed. If the marriage took place he might have hoped to benefit from such a close relationship with the wealthy Mr Darcy; what livings might not be within his power to bestow? But prudence and revenge had probably been more powerful and sweeter motives. He had never forgiven Elizabeth for refusing him. Her punishment should have been a lonely indigent spinsterhood, not a glittering marriage which even an earl’s daughter would not have scorned. Had not Lady Anne married Darcy’s father? Charlotte, too, might have had cause for a more justified resentment. She was convinced, as was the whole of Meryton, that Elizabeth hated Darcy; she, her only friend, who had been critical of Charlotte’s own marriage based on prudence and the need for a home, had herself accepted a man she was known to detest because she could not resist the prize of Pemberley. It is never so difficult to congratulate a friend on her good fortune than when that fortune appears undeserved.

Charlotte’s marriage could be regarded as a success, as perhaps all marriages are when each of the couple gets exactly what the union promised. Mr Collins had a competent wife and housekeeper, a mother for his children and the approval of his patroness, while Charlotte took the only course by which a single woman of no beauty and small fortune could hope to gain independence. Elizabeth remembered how Jane, kind and tolerant as always, had cautioned her not to blame Charlotte for her engagement without remembering what it was she was leaving. Elizabeth had never liked the Lucas boys. Even in youth they had been boisterous, unkind and unprepossessing and she had no doubt that, as adults, they would have despised and resented a spinster sister, seeing her as an embarrassment and an expense, and would have made their feelings known. From the start Charlotte had managed her husband with the same skill as she did her servants and her chicken houses, and Elizabeth, on her first visit to Hunsford with Sir William and his daughter, had seen evidence of Charlotte’s arrangements to minimise the disadvantage of her situation. Mr Collins had been assigned a room at the front of the rectory where the prospect of viewing passers-by, including the possibility of Lady Catherine in her carriage, kept him happily seated at the window while most of his free daytime hours, with her encouragement, were spent gardening, an activity for which he displayed enthusiasm and talent. To tend the soil is generally regarded as a virtuous activity and to see a gardener diligently at work invariably provokes a surge of sympathetic approval, if only at the prospect of freshly dug potatoes and early peas. Elizabeth suspected that Mr Collins had never been so acceptable a husband as when Charlotte saw him, at a distance, bent over his vegetable patch.

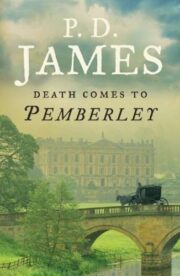

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.