“Colonel Fitzwilliam will have had experience of army courts martial and you may feel that any advice I could offer would be redundant, particularly as the colonel has local knowledge, which I lack.”

Darcy turned to Colonel Fitzwilliam. “I think you will agree, Fitzwilliam, that we should take any legal help available.”

The colonel said evenly, “I am not and have never been a magistrate, and I can hardly claim that my occasional experience of courts martial qualifies me to claim expertise in civil criminal law. As I am not related to George Wickham, as is Darcy, I can have no locus standi in this matter except as a witness. It is for Darcy to decide what advice would be useful. As he himself admits, it is difficult to see how Mr Alveston could be of use in the present matter.”

Darcy turned to Alveston. “It would seem an unnecessary waste of time to be riding daily between Highmarten and Pemberley. Mrs Darcy has spoken to her sister and we all hope that you will accept our invitation to remain here at Pemberley. Sir Selwyn Hardcastle may require you to defer your departure until the police investigation is finished although I hardly feel he would be justified after you have given evidence to the coroner. But will not your own practice suffer? You are reputed to be exceptionally busy. We should not accept help to your detriment.”

Alveston said, “I have no cases requiring my personal attendance for another eight days, and my experienced partner could keep routine matters running smoothly until then.”

“Then I would be grateful for your advice when you feel it is appropriate to give it. The lawyers who act for the Pemberley estate deal mostly with family matters, chiefly wills, the purchase and sale of property, local disputes, and have as far as I know little if any experience of murder, certainly not at Pemberley. I have already written to tell them what has happened and will now send another express to let them know of your involvement. I must warn you that Sir Selwyn Hardcastle is unlikely to be cooperative. He is an experienced and just magistrate, minutely interested in the detective processes normally left to the village constables and watchful always for any intrusion on his powers.”

The colonel made no further comment.

Alveston said, “It would be helpful – at least I would find it so – if we could first discuss our initial response to the crime, particularly having regard to the defendant’s apparent confession. Do we believe Wickham’s assertion that he meant by his words that if he hadn’t quarrelled with his friend, Denny would never have stepped out of the chaise to his death? Or did he follow Denny with murderous intent? It is largely a question of character. I have never known Mr Wickham but I understand that he is the son of your late father’s steward and that you knew him well as a boy. Do you, sir, and the colonel believe him capable of such an act?”

He looked at Darcy who, after a moment’s hesitation, replied, “Before his marriage to my wife’s younger sister we rarely met for many years and never afterwards. In the past I have found him ungrateful, envious, dishonest and deceitful. He has a handsome face and an agreeable manner in society, especially with ladies, which procure him general favour; whether this lasts on longer acquaintance is a different matter but I have never seen him violent or heard that he has been guilty of violence. His offences are of the meaner kind and I prefer not to discuss them; we all have the capacity to change. I can only say that I cannot believe that the Wickham I once knew, despite his faults, would be capable of the brutal murder of a former comrade and a friend. I would say that he was a man averse to violence and would avoid it when possible.”

Colonel Fitzwilliam said, “He confronted rebels in Ireland to some effect and his bravery has been recognised. We have to grant his physical courage.”

Alveston said, “No doubt if there is a choice between killing or being killed he would show ruthlessness. I do not mean to disparage his bravery, but surely war and a first-hand experience of the realities of battle could corrupt the sensitivities of even a normally peaceable man so that violence becomes less abhorrent? Should we not consider that possibility?”

Darcy saw that the colonel was having difficulty in controlling his temper. He said, “No man is corrupted by doing his duty to his King and country. If you had ever had experience of war, young man, I suggest you would be less disparaging in your reaction to acts of exceptional bravery.”

Darcy thought it wise to intervene. He said, “I read some of the accounts of the 1798 Irish rebellion in the paper, but they were only brief. I probably missed most of the reports. Wasn’t that when Wickham was wounded and earned a medal? What part exactly did he play?”

“He was involved, as was I, in the battle on 21st June at Enniscorthy when we stormed the hill and drove the rebels into retreat. Then, on 8th August, General Jean Humbert landed with a thousand French troops and marched south towards Castlebar. The French general encouraged his rebel allies to set up the so-called Republic of Connaught and on 27th August he routed General Lake at Castlebar, a humiliating defeat for the British Army. It was then that Lord Cornwallis requested reinforcements. Cornwallis kept his forces between the French invaders and Dublin, trapping Humbert between General Lake and himself. That was the end for the French. The British dragoons charged the Irish flank and the French lines, at which point Humbert surrendered. Wickham took part in that charge and was then engaged in rounding up the rebels and breaking up the Republic of Connaught. This was bloody work as rebels were hunted down and punished.”

It was obvious to Darcy that the colonel had given this detailed account many times before and took some pleasure doing so.

Alveston said, “And George Wickham was part of that? We know what was involved in putting down a rebellion. Would not that be enough to give a man, if not a taste for violence, at least a familiarity with it? After all, what we are trying to do here is to arrive at some conclusion about the kind of man George Wickham had become.”

Colonel Fitzwilliam said, “He had become a good and brave soldier. I agree with Darcy, I can’t see him as a murderer. Do we know how he and his wife have lived since he left the army in 1800?”

Darcy said, “He has never been admitted to Pemberley and we have never communicated, but Mrs Wickham is received at Highmarten. They have not prospered. Wickham became something of a national hero after the Irish campaign and that ensured that he was usually successful in obtaining employment, but not in keeping it. Apparently the couple went to Longbourn when Mr Wickham was unemployed and money was scarce, and no doubt Mrs Wickham enjoyed visiting old friends and boasting about her husband’s achievements, but the visits seldom lasted beyond three weeks. Someone must have been helping them financially, and on a regular basis, but Mrs Wickham never explained further, and nor, of course, did Mrs Bingley ask. I am afraid that is all I know, or indeed wish to know.”

Alveston said, “As I have never met Mr Wickham before Friday night, my opinion of his guilt or innocence is based not on his personality or record, but solely on my assessment of the evidence as it is so far available. I think he has an excellent defence. The so-called confession could mean nothing more than his guilt at provoking his friend to leave the chaise. He was in liquor, and that kind of maudlin sentimentality after a shock is not uncommon when a man is drunk. But let us look at the physical evidence. The central mystery of this case is why Captain Denny plunged into the woodland. What had he to fear from Wickham? Denny was the larger and stronger man and he was armed. If it was his intention to walk back to the inn, why not take the road? Admittedly the chaise could have overtaken him, but as I said, he was hardly in danger. Wickham would not have attacked him with Mrs Wickham in the chaise. It will probably be argued that Denny felt constrained to leave Wickham’s company, and immediately, because of disgust for his companion’s plan to leave Mrs Wickham at Pemberley without her having been invited to the ball, and without giving Mrs Darcy notice. The plan was certainly ill mannered and inconsiderate, but hardly warranted Denny’s escape from the chaise in such a dramatic manner. The woodland was dark and he had no light; I find his action incomprehensible.

“And there is stronger evidence. Where are the weapons? Surely there must be two. The first blow to the forehead produced little more than an effusion of blood which prevented Denny from seeing where he was and left him staggering. The wound on the back of the head was made with a different weapon, something heavy and smooth-edged, perhaps a stone. And from the account of those who have seen the wound, including you Mr Darcy, it is so deep and long that a superstitious man might well say that it was made by no human hand, certainly not by Wickham’s. I doubt whether he could easily have lifted a stone of that weight high enough to drop it precisely where aimed. And are we to suppose that by coincidence it lay conveniently close to hand? And there are those scratches on Wickham’s forehead and hands. They certainly suggest that he could have lost himself in the woodland after first coming across Captain Denny’s body.”

Colonel Fitzwilliam said, “So you think if it goes to the assize he will be acquitted?”

“I believe on the evidence so far that he should be, but there is always a risk in cases where no other suspect is in question that the jury will ask themselves, if he did not do it, who did? It is difficult for a judge or defence counsel to warn a jury against this view without at the same time putting it into their minds. Wickham will need a good lawyer.”

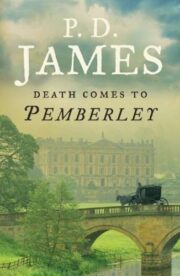

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.