Elizabeth said, “You and Belton should get your sleep tonight. Mrs Bingley and I should be able to manage.”

Returning to the hall, Darcy saw Lydia being half-carried up the stairs by Bingley and Jane, led by Mrs Reynolds. The whooping had sunk into quieter sobbing, but she wrenched herself free from Jane’s supporting arms and, turning, fixed a furious gaze on Darcy. “Why are you still here? Why don’t you go and find him? I heard the shots, I tell you. Oh my God – he could be injured or dead! Wickham could be dying and you just stand there. For God’s sake go!”

Darcy said calmly, “We are getting ready now. I shall bring you news when we have any. There is no need to expect the worst. Mr Wickham and Captain Denny may be already heading this way on foot. Now try to rest.”

Murmuring reassurance to Lydia, Jane and Bingley had at last gained the top step and, following Mrs Reynolds, moved out of sight down the corridor. Elizabeth said, “I am afraid Lydia will make herself ill. We need Dr McFee; he could give her something to calm her.”

“I have already ordered the chaise to collect him, and now we must go into the woodland to look for Wickham and Denny. Has Lydia been able to tell you what happened?”

“She managed to control her weeping long enough to blurt out the main facts and to demand that her trunk be brought in and unlocked. I could almost believe that she is still expecting to go to the ball.”

It seemed to Darcy that the great entrance hall of Pemberley, with its elegant furniture, the beautiful staircase curving up to the gallery, and the family portraits, had suddenly become as alien as if he were entering it for the first time. The natural order which from boyhood had sustained him had been overturned and for a moment he felt as powerless as if he were no longer master in his house, an absurdity which found relief in an irritation over details. It was not Stoughton’s job, nor was it Alveston’s, to carry luggage, and Wilkinson, by long tradition, was the only member of the household who, apart from Stoughton, took his orders directly from his master. But at least something was being done. Lydia’s luggage had been carried in and the Pemberley chaise would go now to fetch Dr McFee. Instinctively he moved to his wife and gently took her hand. It was as cold as death but he felt her reassuring, answering pressure and was comforted.

Bingley had now come down the stairs and was joined by Alveston and Stoughton. Darcy briefly recounted what he had learned from Pratt, but it was apparent that Lydia, despite her distress, had indeed managed to gasp out the essentials of her story.

Darcy said, “We need Pratt to point out where Denny and Wickham left the carriage, so we shall be taking Piggott’s chaise. You had better stay here, Charles, with the ladies, and Stoughton can guard the door. If you will be part of this, Alveston, we should be able to manage between us.”

Alveston said, “Please use me, sir, in any way in which I can be of help.”

Darcy turned to Stoughton. “We may need a stretcher. Is there not one in the room next to the gunroom?”

“Yes sir, the one we used when Lord Instone broke his leg in the hunt.”

“Then fetch it, will you. And we shall need blankets, some brandy and water and lanterns.”

Alveston said, “I can help with those,” and immediately the two of them were gone.

It seemed to Darcy that they had spent too long talking and making arrangements, but looking at his watch he saw that only fifteen minutes had passed since Lydia’s dramatic arrival. It was then that he heard the sound of hoofs and, turning, saw a horseman galloping on the greensward at the edge of the river. Colonel Fitzwilliam had returned. Before he had time to dismount, Stoughton came round the corner of the house carrying a stretcher over his shoulder followed by Alveston and a manservant, their arms laden with two folded blankets, the bottles of brandy and water and three lanterns. Darcy went up to the colonel and rapidly gave him a concise account of the night’s events and what they had in mind.

Fitzwilliam listened in silence, then said, “You are mounting quite an impressive expedition to satisfy one hysterical woman. I daresay the fools have lost themselves in the woodland, or one of them has tripped over a tree root and sprained an ankle. They are probably even now limping to Pemberley or the King’s Arms, but if the coachman also heard shots we had better go armed. I’ll get my pistol and join you in the chaise. If the stretcher is needed you could do with an extra man and a horse would be an encumbrance if we have to go into the depths of the woodland, which seems likely. I will bring my pocket compass. Two grown men getting themselves lost like children is stupid enough, five would be ludicrous.”

He mounted his horse and quickly trotted towards the stables. The colonel had offered no explanation of his absence and Darcy, in the trauma of the evening’s events, had given no thought to him. He reflected that wherever Fitzwilliam had been, his return was inopportune if he were to hold up the enterprise or demand information and explanations which no one could yet supply, but it was true that they could do with an extra man. Bingley would stay to look after the women, and he could, as always, rely on Stoughton and Mrs Reynolds to ensure that all doors and windows were secure and to cope with any inquisitive servants. But there was no undue delay. His cousin was back within a few minutes and he and Alveston lashed the stretcher to the chaise, the three men got in and Pratt mounted the leading horse.

It was then that Elizabeth appeared and ran up to the chaise. “We’re forgetting Bidwell. If there’s any trouble in the woodland, he should be with his family. Perhaps he is already. Has he left to go home yet do you know, Stoughton?”

“No madam. He is still polishing the silver. He was not expecting to go home until Sunday. Some of the indoor staff are still working, madam.”

Before Elizabeth could reply, the colonel got quickly out of the chaise saying, “I’ll fetch him. I know where he will be – in the butler’s pantry,” and he was gone.

Glancing at her husband’s face, Elizabeth saw his frown and knew that he was sharing her surprise. Now that the colonel had arrived it was apparent that he was determined to take control of the enterprise in all its aspects, but she told herself that this was not perhaps surprising; he was, after all, accustomed to assuming command in moments of crisis.

He returned quickly, but without Bidwell, saying, “He was so distressed at leaving his work half-finished that I did not press the matter. As usual on the night before the ball Stoughton has already arranged for him to stay overnight. He will be working all day tomorrow, and his wife will not expect to see him until Sunday. I told him that we would check that all is well at the cottage. I hope I have not exceeded my authority.”

Since the colonel had no authority over the Pemberley servants to be exceeded, there was nothing Elizabeth could say.

At last they moved off, watched from the door by a small group consisting of Elizabeth, Jane, Bingley and the two servants. No one spoke and when, minutes later, Darcy looked back, the great door of Pemberley had been closed and the house stood as if deserted, serene and beautiful in the moonlight.

2

No part of the Pemberley estate was neglected but, unlike the arboretum, the woodland to the north-west neither received nor required much attention. Occasionally a tree would be felled to provide winter fuel or timber for structural repairs to the cottages, and bushes inconveniently close to the path would be cut back or a dead tree chopped down and the trunk hauled away. A narrow lane rutted by the carts delivering provisions to the servants’ entrance led from the gatehouse to the wide courtyard at the rear of Pemberley, beyond which were the stables. From the courtyard, a door to the back of the house led to a passage and the gunroom and steward’s office.

The chaise, burdened with the three passengers, the stretcher and two bags belonging to Wickham and Captain Denny, was slow-moving and all three passengers sat in silence which, in Darcy, was close to an unaccountable lethargy. Suddenly the chaise shook to a stop. Rousing himself, Darcy looked out and felt the first sharp rain stinging his face. It seemed to him that a great fissured cliff face hung over them, bleak and impenetrable which, even as he looked, trembled as if about to fall. Then his mind took hold of reality, the fissures in the rock widened to become a gap between closely planted trees, and he heard Pratt urging the unwilling horses onto the woodland path.

Slowly they moved into loam-smelling darkness. They had been travelling under the eerie light of the full moon which seemed to be sailing before them like some ghostly companion, at one moment lost and then reappearing. After some yards, Fitzwilliam said to Darcy, “We would be better on foot from now on. Pratt may not be precise in memory and we need to keep a close watch for the place where Wickham and Denny entered the woodland and where they may have come out. We can see and hear better outside the chaise.”

They got out of the chaise carrying their lanterns and, as Darcy had expected, the colonel took his place at the front. The ground was softened with fallen leaves so that their footfalls were muted and Darcy could hear little but the creak of the chaise, the harsh breathing of the horses and the rattle of the reins. In places the boughs overhead met to form a dense arched tunnel from which only occasionally he could glimpse the moon, and in this cloistered darkness all he could hear of the wind was a faint rustling of the thin upper twigs, as if they were still the habitation of the chirping birds of spring.

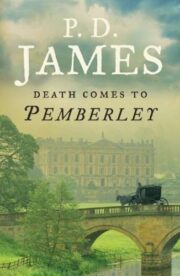

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.