I still want her. I cannot disguise it from myself. No one else will ever do. Only Elizabeth.

I knew it as I stood there, unable to leave, whilst the gardener looked at me curiously and her aunt and uncle watched me from a distance and I knew I must depart, but could not.

At last I tore myself away and went indoors, making sure that the house was ready to receive my guests, as had been my original plan. But I could not remain long indoors. I wanted to be near her, and to show her that her reprovals had been attended to; that I was no longer insufferable or disdainful of the feelings of others; that I had changed.

And so I left the house. I found her at last as she walked by the river. She was at that part of the grounds where the path is open and I saw her long before I reached her. I could tell she saw me, too. The walk seemed endless. A turning in the path hid her from view and then I was suddenly in front of her. Mindful of her previous words about my incivility, I set out to please and to charm her. She seemed to sense it and to want to imitate my politeness. She remarked on the beauty of the place, then blushed and fell silent, as if remembering that, had she accepted my proposal, it could have been hers. Any other woman would have made it hers, even if she despised me. But not Elizabeth. Only love will do for her. And I have known, deep down, for many years, that only love will do for me.

Our conversation faltered and I asked if she would do me the honour of introducing me to her friends. Something of her mischievousness returned, for she smiled with a gleam in her eye as she introduced them as her aunt and uncle. I was surprised; I knew they lived in Cheapside and had therefore not expected them to be so fashionable. To please her, and to show her I was not the rude, arrogant and unfeeling man she thought me, I walked with them, all the time wondering how I could make sure I saw her again. Her party were on a travelling holiday and I did not want them to leave Derbyshire, and so I hit upon the happy notion of inviting her uncle to fish at Pemberley.

And so we continued, the two ladies in front and the two gentlemen behind. I was just wondering how I could alter things when luck played into my hands. Her aunt became tired and leant on her husband’s arm, leaving me free to walk with Elizabeth. There was a silence, but I was not anxious. I was content to catch her scent and to watch the play of colour on her cheek. But she was not easy and soon made it clear that she had been told the family were away from home, and that she would not have taken the liberty of visiting Pemberley otherwise.

I blessed my good fortune. A day later and I would have been in residence, in which case she would not have come; a day earlier and I would have been in London and missed her. I acknowledged that I had arrived earlier than expected and told her that Bingley and his sisters would be joining me.

It was not a happy thought. She became withdrawn and I could tell that her thoughts had returned to her sister and my interference in the matter of Bingley’s attentions. I sought to divert her and found a happy topic in my own sister, asking if I might introduce Georgiana to her during her stay at Lambton. She was surprised, but agreed, and I was content. I would very much like the two of them to come to know each other.

We walked on in silence, each deep in thought. My mind was wondering how I could have stayed away from her so long and wondering how soon I could offer her my hand again. Her mind I did not know, but I hoped it was not entirely set against me.

We reached the carriage and I invited her to walk into the house as her relations were some quarter of a mile behind. She declined, saying she was not tired, and we talked of nothing in particular but each one of us, I am sure, was thinking a great deal. At last her aunt and uncle joined us and the three of them departed.

My thoughts were turbulent, as you might imagine, but the following morning I took Georgiana to meet her and the two of them liked each other. Bingley was with us, and talked of the Netherfield ball. It showed me once and for all that he has not forgotten Miss Bennet, and I am now resolved to do everything in my power to encourage him to see her again.

The meeting was not without its embarrassments, but they were less than formerly and I courted the good opinion of not only Elizabeth but her relations. She saw it, and from time to time a gleam of astonishment lit her eye. I had not realised until then how rude my behaviour had been at Netherfield, for my present civility surprised her.

We stayed only half an hour. I wanted to stay longer. I would have been happy to remain there for the rest of my life. But courtesy compelled me to take my leave—not, however, until I had secured her promise to dine with us the following day.

The evening passed slowly but not unpleasantly, and when my guests had gone to bed I walked the halls of Pemberley, imagining Elizabeth’s step on the stairs, her laughter in the garden, her singing in the drawing room, her brightness and vivacity filling the house and bringing it back to life; for ever since my parents died, a part of Pemberley has been dead.

Her visit to take tea with Georgiana the following day only intensified my feelings and all was going well until this morning, when I paid a visit to the inn at Lambton and found Elizabeth in a state of great distress. I was immediately alarmed and thought she must be ill, but she broke down and revealed that she had just received a letter from home, and that her sister Lydia had run away with George Wickham!

I longed to comfort her, to go to her and put my arms around her, to let her cry against my shoulder, but I could do nothing without outraging propriety and occasioning gossip, so I did what little I could, sending for her aunt and uncle. But I am determined not to rest until I have rescued her sister and relieved her from the agony of this despicable affair.

And so now you see why it is imperative I find Wickham.

I hope you can decipher this letter. I am writing it in the carriage and the potholes are playing havoc with my penmanship. I never thought it would be so long but my feelings have run away with me. A glance out of the window shows me that we are approaching London and I must finish my letter quickly. I must right this wrong, for my own sake as well as Lydia Bennet’s. If I had explained his character, given some hint of it when I was at Netherfield last autumn, this could not have happened. The girl would have been on her guard against him; or, at least, if she was too foolish to heed the warning, then Forster would have been alerted to the danger and kept a better eye on her.

I pray you are still in London and that I will find you there, but if not, I will leave this letter for you at Fitzwilliam House. Come to me at once, and of course say nothing of this to anyone. All may yet be well and the girl’s reputation saved. Though she is not a blameless innocent, as Georgiana was, still she does not deserve this, and neither does Elizabeth.

Darcy

Miss Susan Sotherton to Mrs Charlotte Collins

Bath, August 9

How very glad I was to hear your exciting news. If it is a girl, I hope she grows up to be just like you, if a boy, I hope he grows up like…well, I cannot think of any suitable man for him to emulate. It would certainly be better if he did not grow up like any of the men in my family. I hope he grows up to be someone very good and brave and intelligent. In fact, if he is a boy, I think it would be simpler if he should just grow up to be like you as well! Pray let me be a godmother.

My news is less exciting, but glorious nonetheless. I have chosen my wedding dress. Madame Chloe is to make it for me, after one of the fashions in La Belle Assemblée. It is in the latest Grecian style, with a high waist, a round neck, short sleeves and a sash. I am enclosing a sketch so that you can see how delicious it is. Mama and I are going to London tomorrow to buy the silk at Grafton House. We intend to stay there for a few days so that we can buy everything else I will need as well; all except my shoes, which I am having made here in Bath. They will be made of white silk to match the dress.

I never thought my wedding outfit would be half so fine. Indeed, there were times in the last few years when I thought I would have to dress in rags, but now that I am to marry a rich husband I can buy whatever I please. I am very vain, I dare say, but I am enjoying every minute of it.

We are going to have the ceremony in Bath. I did hope, when Elizabeth said Mr Bingley had left Netherfield, that he would give notice, then we could return there for a few months and I could be married from home. But although Mr Bingley stays away, it seems he does not want to relinquish his tenancy. I am disappointed for my own sake but I am pleased for Jane. I have quiet hopes that he keeps Netherfield Park because he wants to see her again, and wishes to continue his pursuit of her. Let us hope so, for never a dearer creature lived than Jane Bennet.

By the bye, do you have Elizabeth’s address? I know she is in Derbyshire with her aunt and uncle, and her last letter told me where she expected to be for the next week, but I have somehow misplaced it. Or, to tell the truth, my father burnt it with a pile of other papers in a fit of rage. I believe he thought it was a bill. You will tell from this that he is no better and that we all despair of him ever retrenching and conserving what little is left of his fortune. Luckily, I will soon be married and I will not have to worry about his temper any longer, nor his drinking nor his gambling nor anything else. I am very glad my dear Mr Wainwright has none of these vices; he is the most amiable man that ever lived and I am very much looking forward to being his wife.

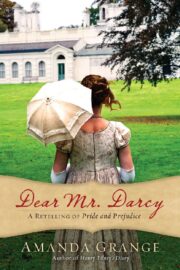

"Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice" друзьям в соцсетях.