Have you told Charlotte yet? Do you think you ever will? And what about Jane? She will want to know, even if it hurts her to begin with, I am sure of it. And anyway, there is no need to tell her that Mr Darcy interfered in her own life, only that he proposed to you. When will you be seeing her again? It is so exciting. And that is always the way of things; either there is nothing to tell, but one has perfect liberty to tell it, or something so momentous it would rock everyone, but one is unable to breathe a word!

Write to me soon, dearest, you know you can tell me anything, and I promise faithfully to keep your confidence, whatever it costs me!

Your loving friend,

Susan

Miss Elizabeth Bennet to Miss Susan Sotherton

Hunsford, near Westerham, Kent,

April 23

My dearest Susan,

I must unburden myself again, and again I must swear you to secrecy, for I have had such a letter…When I think of it, I…But let me collect myself. Charlotte is busy about her household affairs and Maria is helping her, Mr Collins is out in the garden and I am alone in the house. Only now am I able to drag myself out of my thoughts, and needing someone to turn to, someone to tell…

By now you will have had my previous letter, about Mr Darcy’s proposal. I was angry with him, disgusted with his behaviour, but now…

I do not know what to think. He has written me a letter, and such a letter…I expected nothing from him, I thought he would avoid me, since I knew that he intended to return to London very soon, but instead, this morning as I walked, I found him waiting for me. I tried to avoid him but he detained me by stepping forward and calling my name. He held out a letter, which I instinctively took, and said haughtily that he had been walking in the grove for some time in the hope of meeting me, and then asked me to have the goodness to read the letter.

With no expectation of pleasure, but with the strongest curiosity, I opened it, and to my increasing sense of wonder I saw an envelope containing two sheets of paper, written quite through in a very close hand. The envelope itself was likewise full. I did not know what he could have to say to me, let alone what he could have to say which would take so much saying, but I could not contain my curiosity.

I cannot begin to tell you my feelings as I read everything contained therein; indeed, it is only now, several hours later, that I can begin to sort them out. Everything was presented to me with such a different slant that I find myself, against my will, beginning to see things differently; or, at least, to acknowledge that there might be a different interpretation to be put upon things.

The letter started arrogantly enough, all pride and insolence, saying that I had accused him of two offences in my rejection of him. He claimed that, although he knew his friend was becoming increasingly attached to Jane, he convinced himself by watching her that her feelings were not similarly touched. I was at first outraged by this, until I remembered Charlotte saying that Jane ought to show what she felt if she wanted to attach Mr Bingley. Susan, reluctant though I am to do it, I find I have to admit that Jane’s feelings, though fervent, were little displayed, and that there was a constant complacency in her manner not often associated with great sensibility.

His comments on my family, though mortifying, I could not help admitting had some justice. You left Meryton before the militia arrived and so you do not know how my sisters have been throwing themselves at the officers’ heads, whilst Mama and Papa did nothing to stop them.

But it is in his details of his dealings with Mr Wickham that he chiefly sought to exonerate himself. At first I did not believe it, for his account of events differed so strongly from Mr Wickham’s account, but he referred me to his cousin if I doubted him, and this helped convince me that he was not misleading me. Then, too, when I was forced to think about Mr Wickham’s behaviour, I had, in the end, to think it was not as spotless as it first appeared.

I cannot tell you all, but I can say this: that Mr Darcy claims his father left the living to Mr Wickham provisionally only, and that, as Mr Wickham did not want it, Mr Darcy gave him the sum of three thousand pounds instead.

At first I doubted, but as I thought back over my acquaintance with Mr Wickham it struck me as odd that he had confided so much at our first meeting, which was surely wrong of him, and that he had not noised his grievances in public until Mr Darcy had left the neighbourhood and was therefore no longer in a position to defend himself.

And now I am left feeling perplexed and wounded, scarcely knowing what to think, who to believe. To begin with, I believed resolutely in Mr Wickham, but Mr Darcy’s story had the ring of truth and, together with the fact that he referred me to his cousin—who is an honest and upright man—I find myself believing Mr Darcy.

He was sent to plague me, I am sure of it, first of all with his haughtiness, then with his unwanted attentions, and now with his unsettling news about my favourite. He has brought me nothing but torment. And yet I cannot help thinking that he is a better man than I had supposed and, although undoubtedly proud, much maligned.

How much easier would it have been if Mr Darcy had continued to be a villain, and Mr Wickham a saint. But as Mr Wickham transferred his affections from me as soon as Miss King inherited a sizeable dowry, I am faced with the fact that he was never quite the saint I believed him.

My one consolation is that Mr Darcy is leaving the neighbourhood tomorrow, and that I will not be here much longer, either. How I long to see Jane and the familiar walls of home; how I long to talk with Papa and have everything back to normal.

Your dear friend,

Lizzy

Miss Susan Sotherton to Miss Elizabeth Bennet

Bath, April 24

Lizzy, you are trying me hard! First I must mention nothing of your proposal, and now I can mention nothing about Mr Wickham’s relations with Mr Darcy. I wish I were coming to Meryton again, but there is no chance of it, and after all I am glad, for I do not think I could keep so many secrets if I were to find myself at home again.

You say I know nothing of your sisters’ goings-on, but do not forget that Ellie writes to Lydia and Kitty—indeed a letter from Kitty arrived this morning—and I have seen enough of their correspondence to know how silly they are, but this does not excuse Mr Darcy for saying so. It is up to him, as your lover, to make light of your family’s failings, not to make much of them. Your father and mother are not the most sensible parents, it is true, but at least your father has not gambled away your inheritance and forced you to leave your home. I am not surprised you miss him. My own papa, alas, is no better: every time we think he is improving he relapses, and goes from bad to worse.

I eagerly await your next letter. I fully expect to find that the Archbishop of Canterbury has proposed to you when next you write!

Your loving friend,

Susan

Miss Lydia Bennet to Miss Eleanor Sotherton

Longbourn, Hertfordshire,

April 24

La! Ellie, what do you think? The officers are leaving Meryton, they are to be gone in a month, and what shall we do without them? They are going to be encamped near Brighton. How I wish I could go with them, for it will be deadly dull here without them. I have said so time and time again, and Mama agrees with me and says we should all go to Brighton. It would be a delicious scheme, and I dare say would hardly cost anything at all. Mama would like to go too of all things, but Papa says he will not stir from Longbourn, and we may not go without him. He says Kitty and I are the silliest girls in the country, but I do not think we are as silly as Mary, who has made so many books of extracts her bedroom is full and now she wants a shelf in the library for them. Papa says she may not have one and Mama tells her to wear her hair differently and Mary preaches in return, so that I am sick of the sound of her. If only we could go to Brighton! Papa says he cannot wait for Jane and Lizzy to return, so that he can have some sensible conversation, but what can they have to talk of? Jane has been in London and Lizzy has been in Kent and there are not any officers in either place.

Your greatest friend in all the world,

Lydia

Miss Elizabeth Bennet to Miss Susan Sotherton

Hunsford, near Westerham, Kent,

April 25

Dear Susan,

I know I try you hard, but I shall endeavour not to do so in future. The Archbishop has not proposed and so that is one less secret for you to keep! The gentlemen—Mr Darcy and his cousin—have now left Rosings, and I have only Lady Catherine to contend with.

We dined with her yesterday evening and I could not help thinking that, if I had answered Mr Darcy differently, I might by this time have been presented to her as her future niece. What would she have said? How would she have behaved? I amused myself with these questions as an antidote to an otherwise dull evening.

Lady Catherine mourned the absence of the gentlemen, and Mr Collins alleviated her suffering with some clumsy compliments.

Then she turned her attention to me and thinking, quite wrongly, that I was quiet because I did not like to leave, she said that I must write to my mother to beg that I may stay a little longer. Nothing could be further from my wishes, for I long to be at home. She would not accept it, however, but went on saying that my mother could certainly spare me for a fortnight or so. She dismissed the idea that my father was missing me and added, in her goodness, that she could take either Maria or myself as far as London in early June, though what the other one was supposed to do, I do not know—run behind, I suspect! Though she did say, condescendingly, that as we were neither of us large, if the weather should happen to be cool, she did not mind taking us both.

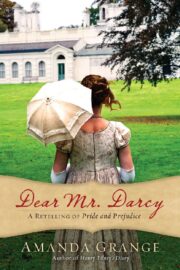

"Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice" друзьям в соцсетях.