Papa has taken out a subscription to the library in Meryton and we are all now frequent visitors. Lydia goes there in the hope of meeting her friends, and with the desire of showing off her latest bonnet; Kitty is very much Lydia’s shadow; Jane and I like to peruse the new books; and Mary is enthralled. She has borrowed a selection of improving books for young women and she reads to us over the breakfast table, then she copies her favourite extracts into a little book.

Did you know, aunt, that ‘One of the chief beauties in a female character is that modest reserve, that retiring delicacy, which avoids the public eye’? Mary has taken this piece of advice so much to heart that yesterday she refused to take tea with my aunt Philips, since she would have to be seen by the public eye when she walked into Meryton, and would therefore lose one of her chief beauties.

Papa asked her whether the public eye were the left one or the right one, and he expressed his deep regret when she could not answer him. He recommended her to discover it, so that she could walk on either the right side or the left side of the road and therefore visit her aunt in safety.

‘Or is it, perhaps, a Cyclopean eye, set in the middle of the forehead?’ he asked. ‘If so, it is something singularly lacking in all of our acquaintance and you might therefore go about as you please.’

It was very wrong of him to tease her, but we are all becoming tired of her moralising.

You ask if there is anything I would like from London. Apart from news of the latest fashions and yourselves, then no, there is nothing. I am eager to see you again.

Your affectionate niece,

Lizzy

1799

JANUARY

Mr Darcy to Mr Philip Darcy

Fitzwater Park, Cumbria,

January 15

Philip, the weather here is dreadful; I hope it is better with you. I have never liked being cooped up indoors for any length of time and I confess myself bored, though I would not say so to my aunt. She has made me very welcome here and she has been kindness itself to Georgiana since we arrived. Georgiana will return to school by and by, but I want her to have some fun with people of her own age before returning to her studies.

We had a full house at Pemberley over Christmas but there were only a few young people and none at all under fifteen, which meant Georgiana was deprived of many of the games she would otherwise have enjoyed. I played chess and backgammon with her, but here she plays at charades and indulges in other childish pursuits; for although she is turning into a young lady there are still days when she wants nothing better than to dress Ullswater in a stole and bonnet and push the gaily attired animal along the corridors in an old perambulator. Ullswater takes it all in good part and wags her tail in enjoyment, and I confess I like nothing better than to see my sister happy.

We were expecting to find Henry here in Cumbria but his leave was cancelled and we do not know when he will next see England. We thought, after Admiral Nelson destroyed the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile last year, that the tide was turning in our favour and that we would see more of him than hitherto. With the French navy decimated and the expeditionary force unable to return to their homeland, it seemed there was some chance of the French suing for peace, but it is becoming increasingly obvious the French are bent on conquering Europe and they will not rest until they have achieved their goal or been thoroughly crushed. Needless to say, we can never consent to the former and so it must be the latter, though it means another five years of war. However, it is good for Henry’s chances of promotion and so we will not complain.

My aunt has arranged another ball for this evening. She has been tireless in her efforts to find me a wife but I am growing increasingly irritated with the whole affair. I have always hated talking to strangers and yet I must do it day after day and it puts me out of temper. It is even worse for the women. They have to try and win my favour and yet as soon as they try to catch my attention, I lose interest in them, for I cannot bear to be courted for my position or my wealth. And yet what alternative is there? Women must have husbands and men must have wives, and so I keep making myself attend all the balls and soirées to which I am invited; and of course I am invited to a great many of them. If not for the fact that I need an heir for Pemberley, I would be content to remain a bachelor. But I do need an heir and so I must do my duty and attempt to find a wife.

I have met any number of accomplished, beautiful and intelligent women from good families, with handsome dowries, but none of them tempt me. I am beginning to wonder if I am too hard to please. And yet I am convinced that the future Mrs Darcy must have something more: some indefinable quality which will make her not only a suitable mistress for Pemberley and a desirable sister for Georgiana, but a captivating and irresistible wife for me.

I remember my father’s words very well. He told me that my wife will need to command the respect of the servants and the love of my family; she must reflect the greatness of the Darcys; she must be a gracious hostess and a model of feminine virtue; she must be a modest lady and she must be possessed of a refined taste and true decorum. And she must be a woman I can admire, respect and esteem, as well as love.

It is a great deal to ask. I fear he was spoilt by his own marriage, and I have been spoilt by it, too. I can still see the expression in my mother’s eyes whenever she looked at him. There was a warm glow there, an unmistakable look of love and affection, and a certain lift to her mouth that I will never forget. If I must marry—and I must—I would like the same. But where am I to find it?

For advice on matters of this nature he referred me to you. We both bear the name of Darcy and we both have the responsibility of upholding the Darcy traditions and continuing the Darcy name. And so I ask you, Philip, have you ever met a woman who was necessary to you? A woman you would be glad to marry? Do you mean to marry when you are thirty, as you have always said, and if so, are you willing to marry without love? And how do you intend to choose your wife from the many caps that are set at you?

Yours,

Darcy

Mr Philip Darcy to Mr Darcy

Wiltshire, January 17

Of course you are hard to please, and so you should be: you are a Darcy. There are very few women who are good enough for you. My mother drew up a list of suitable wives for me before she died, and the same ladies are naturally suitable for you, but of the eleven names on the list, four are already married, one has lost her fortune and two are personally unappealing to me. Of the remaining four, one is your cousin, Anne de Bourgh, and she is sickly and not likely to provide a living heir. The three remaining ladies are all acceptable and I mean to propose to one of them in due course, though I have not yet decided which one. I am sending you a copy of the list in case it is of use to you, and I would be glad of the names of the women deemed suitable by your aunt, as they might perhaps be of use to me.

I am holding a house party next month and you are welcome. I will invite all the young women; it might help us to decide which ones we should favour with our hands if we see them all together.

I do not pretend to be looking for love, for although you say your parents found it—and I bow to your superior knowledge of them—I confess it seems to me that happiness in marriage consists of a large house, so that a husband and wife might speak to each other occasionally if they have a mind to do so, but otherwise go their own separate ways. As Pemberley is one of the largest houses in the country, I do not despair of you finding happiness, even if it is of my sort and not yours.

I am sorry Henry could not get any leave, though I know he would not feel sorry for himself. Ever since we were children he has longed to be a soldier, and now that he is a colonel his happiness is complete—or, perhaps no, he has still something to hope for, as I am sure he would like to become a general. If the war goes on much longer, he might have his wish. For myself, I would like to see an end to the war. I want to go over to Paris but at the moment it is impossible. God knows when it will end.

Have you heard anything of George Wickham lately? I met a friend of his, a Matthew Parker, in town last week. I know nothing of Parker, other than that he comes from a good family, but he says that Wickham is quite changed. He let slip it was a letter from you that brought about the change. I gather you wrote some harsh truths, which have done him more good than all the help he has been given and made him see the error of his ways. I hope it may be so. His father was a good man and I have not forgotten him.

Yours,

PD

Mr Wickham to Mr Darcy

London, January 20

My dear Darcy,

I cannot let the New Year go by without writing to wish you well for the future and without thanking you for everything you have done for me in the past. But above all, I want to thank you for the letter you sent me last summer. I was very angry with you when I received it, for I thought it the most unjust thing I had ever read. But I could not forget it and your words gradually pierced my haze of resentment until at last I was forced to acknowledge the truth of them. I had squandered my chances as well as my resources and I was unfit for the church, as I was unfit for everything else. Your letter made me look at myself and I did not like what I saw. I began to mend my ways and I mean to continue in the same way. I want to make you glad to call me your friend, as you were once before.

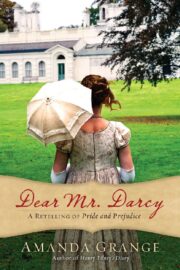

"Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice" друзьям в соцсетях.