I am going to make sure that she has the best of everything. What could I say? I could not say the truth. That you are her father. But you couldn’t look after her, Ennis, not in the way I want her looked after. Charlie’s the one to do that … if ever it were necessary. She’d have servants … nannies … everything. So I say there will be no form filling … no records. This is my child and I will do it my way.

Perhaps I’m wrong, but I think it’s better to do what you can for people, to love them, and there’s no one I want the best for more than my baby. I think love is more important than a lot of moral laws. I am not going to try to make some plaster saint out of her. I want her to laugh her way through life … to enjoy it … above all, I want her to know that she is loved. I know the world would say I’m a right old sinner, but I think that love is the best thing in life … love for one another … and love of life, too. The preachers would say that is wrong. To be good you have to be miserable, but something tells me that if you are loving and kind that’ll be good enough for God when the Day of Judgement comes, and He’ll turn a blind eye to the rest of it.

My child is first with me, and I am going to see that above everything she is happy, and I don’t care what I have to do to make her so.

It was like hearing her voice. It brought her back so clearly to me. She had cared so much for me. It was an ironic twist of fate that, out of her love for me, she had ruined my life.

I felt the tears on my cheeks. These letters had brought her back so vividly that my loss seemed as fresh as it ever had. This they had done—and something else. They had told me without doubt what I had come here to find out.

Marie-Christine had returned. She found me sitting there with the letters in my hand.

She sat down quietly, watching me intently.

“Noelle,” she said at length. “They’ve upset you.”

“The letters …” I replied. “It was just like hearing her talk. It’s all here. There is no doubt that Ennis Masterman is my father.”

“So Roderick is not your brother.”

I shook my head.

She came to me and put her arms round me.

“It’s wonderful. It’s what we wanted to hear.”

I looked at her blankly. “Marie-Christine,” I said slowly. “It doesn’t matter now. It’s too late.”

The next day I called on Ennis Masterman.

I had said to Marie-Christine, “I shall go over to him alone. He is my father, you see. You have been so good. You will understand.”

“Yes,” she said. “I understand.”

He was waiting for me. We stood and looked at each other as though with embarrassment.

Then he said: “You can imagine what this means to me.”

“Yes, and to me.”

“Ever since you were born, I have been hoping to see you.”

“It is strange to be suddenly confronted with a father.”

“At least I knew of your existence.”

“And then I think I might never have known you. It is just by chance …”

“Come in,” he said. “I want to talk about her. I want to hear about your life together.”

So we talked and doing so, surprisingly, I felt some relief from the wounds which had been reopened when I had read her letters. I told him how she had helped Lisa Fennell, of her sudden death and the wretchedness which followed. I told him about the plays, her enthusiasms, her successes.

“She was right,” he said. “She had to do what she did … and I should have been no good for her. She was bent on success and she achieved it.”

At length I talked about myself. I told him of my visit to Leverson Manor, of my love for Roderick and what had come of it.

He was deeply shocked.

“My dear child, what a tragedy!” he said. “And it need never have been. You could have been happily married. And all because of what she had done. Her heart would be broken. What she wanted most of all was for you to be happy … to have everything she missed.”

“It is all too late now. He has married someone else … the Lisa Fennell I told you about.”

“Life is full of ironies. Why did I not follow her to London? Why did I not at least try to make something of myself? I might have been with her in London. I should have been happy there. But I could not do it. Somehow I couldn’t leave this place. I didn’t believe in myself. I always doubted. I was weak and she was strong. I was unsure and she was so certain. We loved each other but, as she said, we did not fit. I was daunted by all the difficulties while she confidently danced her way over them.”

I told him about my stay in France, about Robert, his sister … and Gerard, whom I might have married.

I said: “There were times when I thought I could make something of my life in France, and then memories of Roderick would come back to me. Well, it was decided for me.”

He was thoughtful. “Noelle, I shall give you those letters,” he said. “You will need them as proof. Perhaps you will come and see me sometimes.”

“I will,” I promised. “I will.”

“I wish fervently that you had come before, that I could have known you before it was too late.”

“Oh … so do I. But it was not to be.”

“It would have broken her heart if she knew what she had done.”

It was late in the afternoon when I rode back to the Dancing Maidens. I was still bemused.

I had found my father and confirmed my suspicions. I need never have lost the man I loved.

KENT

Return to Leverson

We went back to London, and I felt saddened rather than elated by the success of our venture. Marie-Christine was a great comfort. She seemed much older than her years and, understanding my feelings, tried to comfort me. She did to a great extent, and I kept telling myself how fortunate I was to have won her affections.

The future looked blank. I wondered what it held. During that time I often thought I might have made a good life in Parisian bohemian circles. It would have been a substitute; but knowing Gerard, and caring for him in a way, had brought home to me the truth that there would never be anyone for me but Roderick.

Oh, why had we not found those letters at the time of my mother’s death? Why had I not told her of my growing friendship with Roderick? How different my life might have been. Marie-Christine threw herself into the project of changing my mother’s room which had been abandoned when we left for Cornwall. But nothing could expunge her memory. It had all been brought back as vividly as ever by my encounter with my father. I was constantly recalling the words she had written. How her love for me came over in those letters! She had not so much defied conventions as ignored them. How often had Dolly cried in exasperation: “You are mad, mad, mad!” But she had blithely pursued some course which might seem wildly preposterous to some, but which was completely logical to her.

It had worked out as she had planned. Charlie had regarded me as his daughter. How could she have foreseen the consequences that would bring?

For several weeks life went on uneventfully, and then Charlie called.

I was delighted to see him. I had been pondering whether I should tell him what I had discovered. I thought it was only right that he, being so involved, should know. I had wondered what he knew about Robert’s death. That was another matter which I should tell him, but I had shrunk from writing to him. And now here he was.

He came into the drawing room and took my hands into his.

“I have just heard what happened,” he said. “Someone in the City told me. How dreadful to think of Robert … dead. I have been wondering for a long time how you were getting on. I did not know you were in London, and called to see If there was any news here. I was planning to go to Paris to see you, but travel is not easy, as things are still in turmoil in France. How glad I am that you are home and safe.”

“Robert was killed with his sister and her son. It was in the Paris house. I, with Robert’s great-niece, was in the country at the time.”

“Thank God for that! Poor Robert! Such a good fellow. All these years I have known him. But you, Noelle …”

I said: “Robert’s great-niece is with me. Marie-Christine … she lost her family, you see … all of them.”

“Poor child.”

“Charlie,” I said. “I have something of great importance to say to you. I have been asking myself whether I ought to write to you … but I wasn’t sure. It has only just happened. I’ve found my father … my real father. It is not you, Charlie.”

“My dear child, what are you saying? What can you know?”

I told him about the discovery of the letters and my visit to Cornwall.

“I have proof,” I told him. “Ennis Masterman has given me letters she wrote, and in them she sets out quite clearly that he is my father.”

“Then why … ?”

“She did it for me. She was afraid she might die and I should not have all she wanted for me. Ennis Masterman was poor. He lives almost like a hermit in a little cottage on the moors, not far from the village where she used to live, and where she had a miserable childhood. She did not want me to be poor … as she had been. It was an obsession with her. She did get obsessions, you know, Charlie. Her determination to succeed … her plans for me. She was very fond of you. She trusted you more than anyone. I think I should show you her letters. They are written to another man … and I daresay you will find reading them harrowing … but you should know the truth. She had so much love to give—to you, to Robert, to my father … and for me the greatest love of all. For me she would lie, cheat if need be … but it was all for me.”

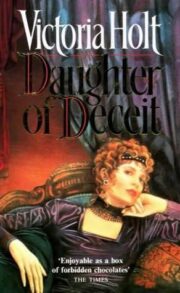

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.