She seemed mollified. / was not going to be famous, so perhaps I would settle down, return to La Maison Grise and continue teaching her English.

I received another letter from Lisa.

I had written in answer to hers and told her that I was feeling better. Robert and his family were so kind to me, and he was the sort of man from whom it was easy to accept hospitality, as she had found. I was feeling cut off from the old life. Here everything seemed so different. I had done the right thing in coming, of course, but I could not stay here indefinitely, though everyone seemed not to want me to go … so here I was.

Dear Noelle [she had written],

Dolly’s Cherry Ripe got off to a wonderful start. Everyone said Lottie was splendid. It was just her piece … less song and dance than usual, and you know she was always shaky on her top notes.

There’s a trapdoor in some of the scenes. The hero comes climbing through it in the first act. He’s pretending to be a workman, but of course he is a millionaire in disguise.

Dolly had made me understudy, which I thought was good for me. I was longing for a chance to show them what I can do. I was really every bit as good as Lottie.

Well, my chance came. My chance! There was an accident! The trapdoor gave way and I fell. It was quite a long way down and I’ve done something to my back. Dancing is out of the question for the time being. I’ve got to rest. I have been to two doctors, and they can’t make up their minds what I’ve done. Dolly is furious. It’>> such a bore. I know I could have had a real chance with Cherry.

/ expect I shall be resting for a few weeks. Well, it has given me a chance to catch up with my correspondence.

I think of you so much, and wonder how you are getting on. It is quite a long time since you went away.

I saw Robert when he came to London. What a dear he is! He insists on my staying in the house, and the Crimps would hate me to go. He said he thought France was doing you a lot of good, and he was going to do his utmost to keep you there. He said his great-niece had taken a fancy to you! It sounds cosy.

By the way, I went to Leverson again. There is such a lot of activity about that Neptune temple. Do write and tell me your news.

My love,

Lisa

Time was speeding by. There was all the activity concerning the exhibition. I went to Paris again with Angele and was at the studio frequently. I enjoyed preparing a meal and then we would eat together, very often joined by one of Gerard’s friends, when conversation would be mainly about art.

Lars Petersen was at that time using a model called Clothilde. It occurred to me that they might be lovers. When I asked Gerard, he laughed and said that Lars often indulged in romantic adventures. It was a way of life with him.

I was becoming more and more drawn into the circle, and I very much missed these occasions when we went back to the country. All the same, I could never escape from my longing for Roderick. I even toyed with the idea of writing to him. But I knew that would be folly. There was nothing either of us could do to alter the situation. It was safer for us to be separated. To see him again would only intensify the pain. I had to cut him right out of my life. There could never be a brother-and-sister relationship between us. If we could not be together as lovers, we must remain apart.

I was glad to find that, in spite of everything, I could still be interested in other people. I was always telling myself that perhaps in time I should feel differently.

It was strange to see my face encased in a rather magnificent brass frame looking down on me from a wall. It certainly was an arresting picture. It was because of the subtle hint of tragedy which Gerard had brought into an otherwise young and innocent face. He had done it with remarkable skill. Had I really looked like that? I wondered.

I walked along the line. Some of the views of Paris were enchanting, but it was the portraits which would attract attention. Madame Garnier looked down at me. I could see her calculating how much she was going to make on her purchases, and I was reminded of her sly smile when I confronted her with her misdeeds and her calmness in brushing them aside. There she was, with all her failings and her virtues. I was beginning to think that Gerard was a very clever artist.

They were exciting days. I was often at the exhibition. I found it difficult to keep away. Gerard was delighted by my enthusiasm.

My picture was talked of, and in the notices which were given of the exhibition, I was mentioned at length.

“Noelle is the pick of the bunch.” “Noelle takes the palm.” “Study of a young girl who has a secret to hide. Deserted by her lover?” “What is Noelle trying to tell us? It is an arresting portrait.”

Madame Garnier was commented on, too. “A fine study.” “Full of character.” “Gerard du Carron has come far in the last years and should go farther.”

I was pleased when someone wanted to buy my portrait and Gerard refused to sell it.

“It’s mine,” he said. “I shall always keep it.”

After the exhibition, we went back to La Maison Grise. I had written to Lisa telling her about my stay in Paris. I did not hear from her for some time, so I presumed she was back at work and busy.

When I first returned, Marie-Christine was inclined to be aloof, but I soon realized that was because she had been hurt by my long absence.

One day, when we were riding together and walking our horses side by side through a narrow lane, she said: “I believe you liked being in Paris better than you do here.”

“I did enjoy being in Paris,” I said, “but I enjoy it here, too.”

“You won’t stay here always, though, will you? You’ll go away.”

“I know you have all made me very welcome, but I am really only a guest. This isn’t my home.”

“It feels like it to me.”

“What do you mean?”

“It feels as though you are part of my home … more than anyone else.”

“Oh … Marie-Christine!”

“I’ve never had anyone like you before. You’re like my sister. I always wanted a sister.”

I was deeply touched. “That’s a lovely thing you have said.”

“It’s true. Grand-mere is kind, but she is old, and she never really liked my mother, and when she looks at me, she thinks of her. My mother noticed me sometimes, and then she seemed to forget. My father didn’t notice me much either. My mother always wanted to be in Paris. My father was always there as well. Uncle Robert is kind … but he’s old, too. I’m just ‘the child’ to him. They’ve got to look after me. It’s not really that they want to. It’s a duty. What I want is a family … people to laugh with and quarrel with. People you can say anything to … and you feel they’re there, however horrid you are to them … they can’t get away because they are family.”

“I did not realize you felt like that, Marie-Christine.”

“You, too. You’ll go away, I know you will. Look how you went to Paris. We used to have fun doing English and French. Your French was very funny.”

“So was your English.”

“Your French was a lot funnier than my English.”

“Impossible!”

She was laughing. “You see? That’s what I mean. We can be rude to each other and we still like each other. That’s what I want, and then you go off to Paris. I reckon you’ll be going there again soon.”

“Well, if I do, I don’t see why you shouldn’t come, too. There’s room in the house there.”

“And what about Mademoiselle Dupont?”

“She could come, too. You could do your lessons there and learn something about the history of the city … right on the spot.”

“My father wouldn’t want to see me, though.”

“Of course he would.”

She shook her head. “I remind him of my mother, and he doesn’t want to be reminded.”

For a few seconds we rode in silence. We came to the end of the lane and she broke into a canter. I followed her. I was a little shaken by our conversation, during which she had revealed the intensity of her feelings for me.

She called over her shoulder: “I want to show you something.”

She pulled up sharply. We had come to a lych-gate. She leaped from her saddle and tethered her horse to a post at the side of the gate. I dismounted. There was a similar post on the other side of the gate, so I tied my horse to this.

She opened the gate and we went through.

We were in a graveyard, and she led the way along a path. All around us were the graves with their elaborate statues and an abundance of flowers.

She paused before one which was presided over by an elaborate carving of the Virgin and Child.

I read the inscription on the stone: “Marianne du Carron. Aged 27 years. Departed this life, January 3, 1866.”

“That,” said Marie-Christine, “is where my mother is buried.”

“It’s beautifully tended.”

“We never come here.”

“Who looks after it?”

“Nounou mostly. Tante Candice perhaps. But Nounou is here every week. She comes on Sundays. I’ve seen her often. She kneels down and prays to God to care for her child. She calls my mother her child. I’ve been close to her and heard. I never let her see me, though.”

I felt a great tenderness towards her. I wanted to protect her, to help to make her happy.

I took her hand and pressed it, and we stood in silence for a few seconds.

Then she said: “Come on, let’s go. I just wanted to show you, that’s all.”

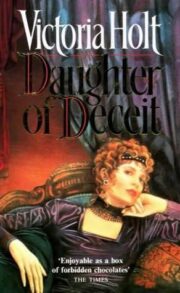

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.