I took the letter to my room so that I might read it without interruptions.

My dear Noelle,

I have been wondering a great deal about you. In fact, I have never ceased to think of you since you left. How are you? I am sure you are feeling better. Robert is the kindest man I know, and you did right to go with him.

The show finished and it will be some weeks before we open with the new one. There is a place for me in it, Dolly has promised. Only in the chorus, though. I think Lottie Langdon is going to take the lead. I’m hoping to get the understudy. But at the moment I am resting.

What do you think? I went down to Leverson. I wanted you to know that I had been.

You see, there was a good deal in the papers about that discovery of the Neptune temple. Apparently it’s a great find and all that about how the landslide had revealed it made good news. I was quite fascinated, and I wrote to Roderick, saying how I should like to see it.

He came up to London. I was still working then and he came to the show. We had dinner afterwards. He seemed very sad. He wouldn’t talk about you, so we discussed this temple and he asked me down for a weekend, so that I could see it. I went. It was fascinating. I loved it all. I met that nice Fiona Vance, and she showed me some of the work she was doing. I had a most interesting weekend. Lady Constance was very cool towards me. Clearly she didn’t approve. I understand how you must have felt.

Apart from that, I enjoyed it very much. I became so interested in what Fiona was doing. She showed me how to brush off the earth and stuff from some of the drinking vessels, and I was ever so sorry when I had to go.

Fiona said it was a pity I didn’t live nearer. Charlie was there. He is very unhappy, too. I am sure you are never far from their thoughts.

Both Charlie and Roderick said I must come again. Lady Constance did not add her invitation to theirs!

Well, perhaps I shall go again. I do find all those Roman relics quite fascinating.

I am still at the house. Please tell Robert I feel ashamed about keeping on there, but I am so comfortable and the Crimps don’t really want me to go. They don’t like caretaking, as they say. They’ve been used to a household where things are going on. I know I don’t make much difference, but I’m there, and they are always interested in what’s happening at the theatre. So I just linger on.

Try to find out from Robert whether he really thinks I ought to go. But really, it does seem rather unnecessary and it means a lot to me to be able to stay here.

I expect I shall soon be working again. I hope so. I shan’t see any more weekends at Leverson in that case.

Well, I thought I ought to let you know that I had been there and seen them. Perhaps I’ll see you sometime. Are you making plans?

Oh, dear Noelle, I do hope that things will go right for you …

The letter fell from my hands.

So, she had been there. She had seen Roderick and Charlie and Lady Constance. They had been sad, she said.

Dear Roderick. What was he thinking of now? Would he forget me in time? I knew I should never forget him.

I found peace and a certain amount of contentment sitting in that studio, gazing across the city while Gerard du Carron worked on my portrait.

I seemed farther away from the past than I had been since tragedy had first struck me. It seemed as though once again a way of escape was opening out before me.

I was seated on a chair with the light falling full on my face while Gerard stood at his easel. Sometimes he talked while he worked; at others he lapsed into silence.

He told me about his childhood at La Maison Grise, how he had always loved to be in the north tower. He had sketched from an early age; he had been deeply interested in pictures.

“I used to study those in the picture gallery. I would be up there for hours at a time. They always knew where to find me. They thought I was a strange child. And then suddenly I knew I wanted to paint.

“Life was smooth and comfortable. My father was a quiet man… a fine man. I wonder what would have happened if he had lived. If … one is always saying if. Do you say it, Noelle?”

“Constantly.”

“Why are you so sad?”

“How do you know I am sad?”

“You try to hide it, but it is there.”

“You know about my mother?”

“Yes. I know of her sudden death. Robert was very fond of her, and that is why you are here. He promised her he would look after you. It is for that … and of course because he is very fond of you. Does it hurt to speak of her?”

“I am not sure.”

“Try it, then.”

So I talked of her. I told him about our life, of the productions, the dramas and Dolly. I kept recalling incidents and found that I could laugh at some, as I had at the time.

He laughed with me.

He said: “It was a tragedy … a great tragedy.”

Madame Gamier would come, and the kitchen was full of noise. I fancied she thought the noise was necessary to show how hard she was working. She was a little resentful of me at first, but after a few days she was more amicable. We had both had our pictures painted, and that made a bond between us.

She told me that hers was going into some exhibition. People would come and look at it and perhaps buy it.

“Who would want me hanging in their salons, mademoiselle?”

“Who would want me?”

She had a habit of nudging me and bursting into laughter. She brought in bread, milk and such things, for which I discovered she overcharged outrageously. I had suspected this because of the cupidity I had seen in her eyes in the portrait. I had put it to the test and found it to be true. I was impressed by Gerard’s perspicacity.

I said to him one day: “Do you know Madame Gamier cheats you over the food?”

“But of course,” he said.

“And you don’t tell her so?”

“No, it’s a small matter. I need her to bring the food. So let her have her little triumphs. It brings her satisfaction. She thinks how clever she is. If she thought I knew, she would lose that satisfaction. Is there not a saying in English, ‘Let sleeping dogs lie’?”

I laughed at him.

I used to go into the kitchen when the morning sitting was over and prepare a meal, which we would share. Angele sometimes called and we would go back together. She was staying in Paris with me. Robert had had to go back to La Maison Grise to deal with some business on the estate. I knew Marie-Christine was put out because we had gone away without her. She would have liked to accompany us, but Mademoiselle Dupont had said lessons must not be further interrupted.

I sometimes stayed at the studio for the afternoons. Often when we were lunching together, people would call. I was beginning to know some of Gerard’s friends. There was Gaston du Pre, a young man from the Dordogne country. He was very poor and was fed mainly by the others. He often appeared at mealtimes and shared what was being eaten. Then there was Richard Hart, son of a country squire from Staffordshire, whose lifelong ambition had been to paint. There were several others, chief among them Lars Petersen, the most successful of them all, since he had achieved some fame through his portrait of Marianne.

He dominated the company on all occasions, partly because he was more successful than the others and partly because of his ebullient personality.

It was a lighthearted life and, after a few days, I felt myself caught up in it. I awoke every morning with a feeling of pleasure. I was enjoying the experience as I had not expected to enjoy anything again.

I looked forward to my little skirmishes with Madame Garnier. I had refused to allow her to continue to overcharge on her purchases, and pointed out the discrepancies to her. She would look at me, her little eyes screwed up to make them even smaller. But she respected me. I imagined her theory was that if people were stupid enough to allow themselves to be cheated, they deserved what they got. So there were no real hard feelings.

I liked to make the meal and often brought in the food. She did not object to this, for there was no profit to be made now, and it enabled her to do less work and to leave earlier. So even though I had spoilt her profitable enterprise, I had made life easier for her in other ways.

Gerard was very amused when I told him of this, and I found I was laughing a good deal.

Most of all, I enjoyed the sitting periods when we talked.

Our friendship grew fast, as it does in such circumstances, and I began to think that life would be dull when the portrait was finished.

One day, when he was working, he said: “There is something else which makes you unhappy.”

I was silent for a few moments, and he stood watching me, his brush poised in his hand. “Is it … a lover?” he asked.

Still I hesitated. I could not bear to talk of Roderick. He was quick to interpret my feelings.

“Forgive me,” he said. “I am inquisitive. Forget I asked.”

He returned to the canvas, but after a short while, he said: “It is not good today. I can work no more. Let us go out and I will show you more of the Latin Quarter. I am sure there is still much you do not know.”

I understood. My mood had changed. It seemed that Roderick was close to me. I had lost my serenity.

As we came out into the street, the atmosphere enveloped me and raised my spirits a little. There was a smell of hot baking bread in the air, and from one of the houses came the sound of a concertina.

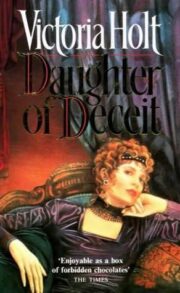

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.