On the gate opening onto a path which led to the house were the words “Moulin Carrefour.”

“Is your aunt expecting us?” I asked.

“Oh no. We are just paying a call.”

“She might not wish to see me.”

“Oh, she will. And she likes to see me. So does Nounou.”

She dismounted and I did the same. We tied our horses to the gatepost and went up the overgrown path.

Marie-Christine took the knocker and let it fall with a resounding bang. There was silence. I felt a little uneasy. We were unexpected. What had suddenly put the idea of visiting her aunt into Marie-Christine’s head?

I was thinking with relief that no one could be at home when the door opened and a face was peering round the edge of it. It belonged to a grey-haired woman who must have been in her late sixties.

“Oh, Nounou,” said Marie-Christine. “I’ve come to see you. And this is Mademoiselle Tremaston, who has come from England.”

“England?” The old woman was peering at me suspiciously, and Marie-Christine went on: “Grand-oncle Robert was a friend of her mother and she was a very famous actress.”

The door was opened wide and Marie-Christine and I stepped into a darkish hall.

“Is Tante Candice home?” asked Marie-Christine.

“No, she is out.”

“When will she be back?”

“I’m sure I don’t know.”

“Then we’ll talk to you, Nounou. How are you?”

“My rheumatism is troubling me. I think you’d better come up to my room.”

“Yes, let’s do that. Perhaps Tante Candice will not be long.”

We went up some stairs and along a corridor until we came to a door which Nounou opened. We entered the room and Nounou signed to us to sit down.

“Well, Marie-Christine,” she said. “It is a long time since you have come to see us. You should come more often. You know Mademoiselle Candice does not care to go up to La Maison Grise.”

“She would come if she wanted to see me.”

“She knows you’ll come here if you want to see her. Are you comfortable, Mademoiselle … ?”

“Tremaston,” said Marie-Christine.

I said I was very comfortable, thanks.

“I am showing Mademoiselle Tremaston our countryside … interesting places and people and all that. And you and Tante Candice are part of that.”

“How do you like it here, mademoiselle?”

“I am finding it all very interesting.”

“It’s a long way to come … from England. I haven’t been away from this place since before Marianne and Candice were born. That’s going back a bit.”

“Nounou came here when they were born, didn’t you, Nounou?”

“Their mother died having them, you see, and someone had to look after them.”

“They were like your own, weren’t they, Nounou?”

“Yes, like my own.” She was sitting there, staring into space, seeing herself, I imagined, arriving at this house all those years ago, come to look after the motherless twins.

She saw my eyes on her and said almost apologetically: “You get caught up with the children you care for. I was nurse to their father. He was a bright one, he was. I looked on him as mine. His mother didn’t care all that much for him. He was a good lad. He had a magic way of making money. It wasn’t going to be the mill for him. He always looked after me. ‘You’ll never want while I live,’ he used to say. Then he got married to that gypsy girl. Him, who’d been such a clever boy all his life … to go and do that! Then he was left with two baby girls. She wasn’t meant to bear children. Some are, some are not. He said to me, ‘Nounou, you’ve got to come back.’ So there I was.”

I said: “I expect that was where you wanted to be.”

Marie-Christine was smiling blandly. I could see she was rather pleased by the turn the conversation was taking. She was looking at me with pride because, I imagine, Nounou was finding me a sympathetic listener.

“Everything was left to me,” she was saying. “They were my girls. Marianne … she was a beauty right from the start. Born that way, she was. I said to myself, ‘We’ve got a handful here.’ Everyone was after her when she grew up a bit. If you’d seen her, you would have understood why. Mademoiselle Candice … she had looks, too, but there was no way she could hold a candle to Marianne. And then … she died like that.”

She was silent for a few moments and I saw the tears on her cheeks.

“How did you get me talking like this?” she asked. “Would you like a glass of wine? Marie-Christine, you know where I keep it. Pour out a glass for Mademoiselle. I’m not sure about you. Perhaps watered down.”

“I don’t want it watered down, Nounou. I will take it as it is,” said Marie-Christine with dignity.

She poured the wine into glasses and handed it round, taking one herself.

Nounou lifted her glass to me. “Welcome to France, mademoiselle,” she said.

“Thank you.”

“I hope you will come again to see us.” She wiped her eyes, in which there were still tears. “You must forgive me,” she went on. “Sometimes I get carried away. It is sad to lose those who have meant so much to us.”

“I know,” I told her.

“One forgets it is only important to oneself. That girl was my life. She was so beautiful … and to think of her carried off. Sometimes it is more than I can bear.”

“I do understand,” I said.

“Now tell me about yourself.”

“I am staying here for a while.”

“Monsieur Bouchere was a great friend of your mother, Marie-Christine tells me.”

“Yes,” put in Marie-Christine. “When her mother died, Mademoiselle Tremaston came to us … to get away from the place where it happened. She is planning what she will do.”

“I hope all will go well with you, my dear. Do you like this wine? I make it myself. France is the country of the best wines.”

Nounou was clearly regretting her outburst and, having betrayed her emotions over the death of Marianne, was now trying to lead the conversation along more conventional lines. We chatted for a while about the neighbourhood and the difference between the French and English way of life—and in the midst of this, Candice arrived.

We heard her coming and Marie-Christine leaped to her feet.

“Tante Candice, Tante Candice … I am here with Nounou! I’ve brought Mademoiselle Tremaston to see you.”

Candice came into the room. She was tall, slim and good-looking, and she reminded me faintly of the picture I had seen of her twin sister, Marianne. Her colouring was similar to that of the girl in the picture, but more subdued; her eyes were more solemn and she completely lacked the expression of mischief which had made the other so arresting. She was a pale shadow of her sister.

She seemed very self-contained and quickly recovered from the surprise of seeing Marie-Christine with a visitor.

I was introduced to her.

“I heard you were at La Maison Grise,” she said. “It’s hard to keep secrets in a village. Marie-Christine is looking after you, I see.”

“We are great friends,” announced Marie-Christine. “I am teaching Mademoiselle Tremaston French and she is teaching me English.”

“That seems a very good arrangement. You knew Monsieur Bouchere in London, I believe.”

“Yes, he was a friend of my mother.”

“Her mother was a famous actress,” said Marie-Christine.

“I have heard that,” said Candice. “Tell me, how are you liking France? It is different, I suppose.”

“Yes, it is, and I am enjoying it.”

“And La Maison Grise is an interesting house, is it not?”

“Very.”

“Have you been to Paris yet?”

“No … not yet.”

“You will go, of course.”

“I hope to … soon. We have talked of it. We shall shop … and I hope to see Marie-Christine’s father’s studio.”

Her face hardened perceptibly. I thought immediately: She has strong feelings about him, and she cannot hide them at the mention of his name.

She said: “Paris is a very interesting city.”

“I very much look forward to a visit.”

“Do you intend to stay long in France?”

“She is going to stay for a long time,” said Marie-Christine. “Great-uncle Robert says she must regard La Maison as her home.”

I said: “My plans are undecided.”

“Because her mother … the famous actress … is dead,” put in Marie-Christine.

“I am sorry,” said Candice. “Death can be … devastating.”

I thought: The memory of Marianne haunts this place. Candice feels it no less than Nounou.

Candice said lightly: “This house was an old mill. I must show you round while you are here. It has just been an ordinary residence since my grandfather’s day, but it still retains some of the old characteristics.”

“I should love to see it,” I said.

“Then let us go now. We’ll come back to you later, Nounou.”

Nounou nodded and we left her.

“It has been my home always,” said Candice. “One gets attached to such places. Of course, I never knew it when the mill was working.”

She showed me the house. It seemed small after La Maison Grise, but then most houses would be. It was comfortable and cosy.

“The Grillons live on the top floor,” she told me. “They look after everything. Jean does the garden and looks after the horse and carriage. He is a very useful man to have about the house. Louise cooks and does the housework. There are just the two of us, and they are adequate. Nounou used to do quite a bit, but she is getting past it now. I’m afraid she meanders on about the past. I hope she wasn’t boring you.”

“She was telling Mademoiselle Tremaston about my mother,” said Marie-Christine.

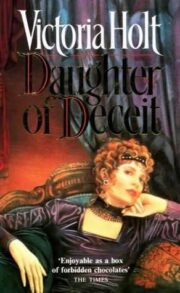

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.