It suddenly struck me as odd that, close friends as we were with Charlie, I did not know his London address. When he was in London he was constantly visiting us. In fact, sometimes it seemed. as though he lived with us. My mother might have visited him, but I never had. The same applied to Robert Bouchere … though, of course, his home was really in France.

All the same, there was a vague mystery about these two men.

They came and went. I often wondered what they were doing when they were not with us.

However, this was an opportunity to see where Charlie had his London residence, and I seized upon it.

I found the house. It was close to Hyde Park. It was small but typically eighteenth century in origin, with an Adam doorway and spiderweb fanlight.

I rang the bell and a neatly dressed parlourmaid opened the door. I asked if I might see Mr. Claverham.

“Would that be Mr. Charles Claverham, miss, or Mr. Roderick?”

“Oh, Mr. Charles, please.”

She took me into a drawing room where the furnishings matched the house. The heavy velvet curtains at the window toned with the delicate green of the carpet and I could not help comparing the simple elegance with our more solid contemporary style.

The parlourmaid did not return. Instead, a young man entered the room. He was tall and slim with dark hair and friendly brown eyes.

He said: “You wanted to see my father. I’m afraid he’s not here just now. He won’t be in until the afternoon. I wonder if I can help?”

“I have a letter for him. Perhaps I could leave it with you?”

“But of course.”

“It’s from my mother. Desiree, you know.”

“Desiree. Isn’t that the actress?”

I thought how strange it was that Charlie, who was one of my mother’s greatest friends, should not have mentioned her to his son.

“Yes,” I said, and gave him the letter.

“I’ll see that he gets it as soon as he comes in. Won’t you sit down?”

I have always been of an enquiring nature and, because there seemed to be something mysterious in my own background, I suspected there might be in others’. I had always wanted to discover as much as I could about the people I met and I was especially interested now. So I accepted with alacrity.

I said: “I wonder we have not met before. My mother and your father are such great friends. I remember your father from the days when I was very small.”

“Well, I don’t come to London much, you know. I have just finished at university and now I expect I shall be a great deal in the country.”

“I have heard of the country house—in Kent, isn’t it?”

“Yes, that’s right. Do you know Kent?”

“I just know it is down in the corner of the map … right on the edge.”

He laughed. “That’s not really knowing Kent. It’s more than a brown blob on a map.”

“Well then, I don’t know Kent.”

“You should. It’s a most interesting county. But then I suppose all places are when you start investigating them.”

“Like people.”

He smiled at me. I could see he wanted to detain me as much as I wanted to stay, and he was trying to think of some subject which would interest me.

I said: “We’re in London all the time. My mother’s profession keeps her there. She’s either getting ready for a play or acting in one. She has to do a lot of rehearsals and that sort of thing. And then she has those times when she’s resting. That’s what they call it when they are waiting for something to turn up.”

“It must be very interesting.”

“It’s fascinating. The house is always full of people. She has so many friends.”

“I suppose she would have.”

“There’s to be a first night soon. At the moment we are at that stage when she is getting anxious as to how it is going to turn out.”

“It must be quite alarming.”

“Oh, it is. She has something to do this afternoon and doesn’t know when she’ll be finished. That is why she has to cancel …”

He nodded.

“Well, I’m having the pleasure of meeting you.”

“Your father must have told you a lot about her. He’s always so interested in the plays. He’s always at first nights.”

He looked a little vague, and I went on: “So you are staying in the country when you leave here?”

“Oh yes. I shall help with the estate.”

“Estate? What does that mean?”

“It’s quite a lot of land … with farms and that sort of thing. We have to manage it. The family has been doing it for centuries. Family tradition and all that.”

“Oh, I see.”

“My grandfather did it … my father did it … and I shall do it.”

“Have you any brothers and sisters?”

“No. I’m the only one. So, you see, it falls on me.”

“I suppose it is what you want.”

“Of course. I love the estate. It’s my home, and now this new discovery … that makes it very exciting.”

“New discovery?”

“Hasn’t my father mentioned it?”

“I don’t remember his ever mentioning anything about the estate. Perhaps he does to my mother.”

“I am sure he must have told her about what has been found there.”

“I haven’t heard. Is it a secret? If it is, I won’t ask about it.”

“It’s no secret. It was in the press. It’s most exciting. They were ploughing up one of the fields near the river. The sea used to come right up to our land a thousand years ago. It has receded over the centuries and we’re now about a mile and a half away. It happens gradually, you know. But what makes it so exciting is that the Romans used the place as a sort of port where they landed supplies, and of course all around was like a settlement. We’ve unearthed one of their villas. It’s a fantastic discovery.”

“Roman remains,” I said.

“Yes, indeed. We’re in Roman country. Naturally we would be. They landed first in Kent, didn’t they? I know the spot in Deal … only a few miles from us. There’s a plaque there which says: ‘Julius Caesar landed here 55 B.C.’ “

“How interesting!”

“You can stand there and imagine all those Romans coming ashore to the astonishment of the Ancient Britons in their woad. Poor things! But it was good in the end. They did so much for Britain. Just imagine how excited we were to find evidence of their being on our land!”

“You are very excited about it, aren’t you?”

“Of course. Particularly as I had studied a little archaeology. Just as a hobby, really. I did feel at one time that I should have liked to make a profession of it, but I knew what I had to do. Noblesse oblige and all that.”

“But you would rather have made archaeology your career?”

“I used to think so. Then I reminded myself that it is fraught with disappointments. One dreams of making miraculous discoveries … but most of it is digging and hoping. For one triumph there are a thousand disappointments. I have been on digs with students. We did not find anything but a few pieces of earthenware which we hoped had come from some Roman or Saxon home of centuries ago, but they turned out to have been thrown out by some housewife a few months before!”

I laughed. “Well, that is typical of life.”

“You are right. And I have been talking about myself all this time, which is an appalling lack of social grace, I believe.”

“Not if the other member of the party is interested, and I have been very much so. Tell me about your own house.”

“It’s ancient.”

“I gathered that … with all those centuries of Claverhams doing their duty to the estate.”

“I sometimes think that houses can dominate families.”

“Presenting a duty to its members who are not sure whether they wouldn’t rather be digging up the past?”

“I see I shall have to be careful what I say to you. You have too good a memory.”

I was rather pleased. There was a suggestion here that he believed this first meeting of ours would not be the only one.

“But it must be wonderful to trace your family back all that time,” I said, remembering that I could not go back farther than my mother.

“Some of the parts of the house are really very old—Saxon in parts, but of course that has been lost in the necessary restorations which have been going on over the years.”

“Is it haunted?”

“Well, there are always legends attached to houses which have been in existence for so long. So naturally we have gathered a few spectres on the way.”

“I’d love to see it.”

“You must. I should like to show you the Roman finds.”

“We never have visited …”I began.

“No? How odd. We have people quite frequently. My mother likes to entertain.”

I was surprised. I had not imagined there was a Mrs. Claverham.

I said: “Mrs. Claverham doesn’t come to London much, I suppose?”

“Actually, she’s known as Lady Constance. Her father was an earl and she keeps the title.”

“Lady Constance Claverham,” I murmured.

“That’s right. Actually, she’s not very fond of London. She might make the occasional trip … buying clothes and things like that.”

“I don’t think she has ever been to see us. I should have known if she had. I’m always there.”

I could see that he thought there was something rather odd— even mysterious—about the situation.

“There are so many people coming in and out of the house,” I went on. “Particularly at times like this when a new show is about to be put on.”

“How exciting it must be to have a famous mother.”

“Yes, it is. And she is the most wonderful person I have ever known. Everybody loves her.”

I told him what it was like when a play was being put on. I told him of the sounds of singing and rehearsals, because there were always some scenes which my mother wanted to go over with certain people, and she would be inclined to summon them to the house for that.

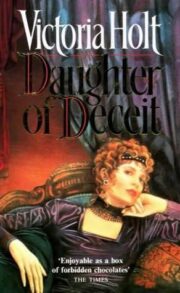

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.