And dealing with her, with his grieving brother, with his nasty excuse for a father, and his forlorn and vulnerable sister, was beginning to drive something inside Darius past reason as well. This mix of woes and worries had been his primary motivation for accepting Lord Longstreet’s scheme—there was coin involved, a great deal of it. Enough to free Darius from the Lucys and Blanches of his life, to provide a small dowry for Leah, to look after Darius’s responsibilities in Kent.

Relief of that magnitude was worth thirty days of dropping his breeches for Vivian Longstreet. Darius had dickered and bargained and feinted and sparred with the lady’s husband at such length because he’d been convinced Lord Longstreet’s plan was his last shot at righting the things off balance in his life.

Before he did something he wouldn’t live to regret.

Tomorrow, Vivian would travel to Kent, there to bide with Darius Lindsey until after the New Year. If anybody asked, William would say she was at Longchamps, and at the end of her month in Kent, to Longchamps she would go.

But as her town coach took her home from a visit to Angela’s busy, noisy townhouse, those thirty days loomed like a prison sentence. In retrospect, she could see she hadn’t used her dinner with Mr. Lindsey very well. She should have been setting out terms—hers—not the dry, legal details William had no doubt focused on, but the pragmatic realities.

She didn’t want Lindsey intruding willy-nilly at any point in her day. She wanted him confined to certain hours or certain parts of the house. In truth, she didn’t want to take meals with him, but to refuse would be insulting.

She didn’t want him entertaining her as if she were a guest, expecting her to ride out with him, risk meeting his neighbors, or God forbid, attend services.

She didn’t want him in her bed, in fact. They’d have to limit themselves to his chambers or maybe a guest room.

And she most assuredly didn’t want him kissing her again. Kissing was by no means necessary to the mechanics of conception.

And she didn’t expect to have to… entice him…

“Blast.” The coach came to a halt in the Longstreet mews, and Vivian’s heart sank further when she saw a groom walking a handsome bay gelding with four white socks. The day needed only a visit from Thurgood Ainsworthy, perpetual stepfather at large.

“Speak of the devil,” Vivian muttered as her butler took her wrap. “Has he been served tea?”

“He virtually ordered it, my lady.” Dilquin’s tone was disapproving. “The knocker has been down since his lordship left yesterday, but that one… Shall we bring a tray?”

“No. Ainsworthy will linger as long as he can over a mere pot of tea. If you could interrupt in about fifteen minutes, I’d appreciate it.”

Dilquin’s lined face suffused with relief, and his gaze went to the eight-day clock in the hall. “Of course, my lady. Fifteen minutes, precisely.”

Vivian spared him a smile then squared her shoulders and prepared to meet her stepfather. It was easy to see—still—why her mother had fallen for the man. Even now, Thurgood was handsome—tallish, though not so tall as Darius Lindsey, say—with soulful brown eyes and blond hair going to wheat gold. He had a superficial charm he put to good advantage when consoling a new widow, and he was clever.

Too clever to underestimate.

“Daughter.” He took Vivian’s hands and drew her close enough that he could kiss her forehead. By sheer force of will, Vivian endured it without flinching. “You look tired, my dear. Should I be concerned?”

Vivian had to discipline herself not to bristle visibly at his avuncular tone.

“I got William off to Longchamps yesterday, and I’ll finish up closing the house today, then follow him myself tomorrow. Moving households is always tiring. Shall we sit?”

He took the chair William usually favored, closest to the fire, and watched while Vivian poured.

“You shouldn’t have to fuss over him like this,” Thurgood said. “He’s a grown man, and since when does the wife close up the house and follow? The ladies are supposed to travel at leisure while the head of the household tends to the more demanding matters.”

“William and I are content with our arrangements.” And if Thurgood were the model, the head of the household never tended to the more demanding matters. “How is Ariadne?”

“Your stepmama sends her love, though I couldn’t encourage her to be out in this miserable cold. I had to see for myself you were doing well since William has left your side.”

“I’ll see him the day after tomorrow.” Vivian told the lie easily. “How is young Ellsworth?”

“Your stepbrother would send his love as well, did he know I was calling upon you.” Such a look of regret. “But he’s a lad, and what passes for cogitation at his age doesn’t bear mention. There is something I wanted to discuss with you, something I’ve been meaning to bring up for quite a while. William is always hovering, though, and a man can hardly find a moment of privacy with his daughter.”

The words I’m not your daughter remained firmly clamped behind Vivian’s teeth. Ariadne wasn’t her stepmother, she was merely Thurgood’s fourth or fifth wife, and Ellsworth the Waddling, Whining Wonder Child was no relation to her at all. But better to let Thurgood have his say and be done with it—for now.

Vivian sipped her tea and presented a placid exterior. “I’m all ears, Steppapa.”

“William is a good man,” Thurgood began, the soul of earnest concern, “but he’s going to shuffle off this mortal coil, Vivian, and you must think of what awaits you then. His parliamentary cronies and titled confreres aren’t your friends, and they’ll do nothing to look after you when William’s gone. You need to assure me now you’ll not try to manage on your own through those unhappy days. Your mother would turn over in her grave were you to live anywhere but with Ariadne and me, letting us protect and guide you in the time to come.”

I must not toss my tea into the face of my guest. “That’s kind of you, and generous, but I couldn’t possibly make that sort of decision without consulting William, and then too, Angela and Jared might be able to use my help with the children.”

Thurgood’s face lit with a credible rendition of indignation. “You must not consider it! That Jared Ventnor would have you as some kind of unpaid nanny for Angela’s pack of brats, and you an earl’s daughter.”

“That pack of brats has an earl’s daughter for a mother.”

“But you could do so much better,” Thurgood insisted. “Angela hadn’t your looks or your poise or your grasp of political affairs. For you, we could aim much higher.”

Just as Vivian’s patience was threatening to snap, Dilquin’s discreet rap sounded on the door.

“Beg pardon, your ladyship, but Mrs. Weir is insistent that you come to the kitchen to supervise the sorting of the linens and spices. Cook claims Longchamps’s inventory is lacking, but the matter requires your attention if she and Mrs. Weir aren’t to come to blows.”

“I’ll be right there.” Vivian rose, while her stepfather tried to hold his ground by staying seated—a subtle betrayal of his upbringing and his true agenda.

“Give me your word, Vivian, that you’ll let me be your haven when grief comes calling. You and I have grieved together before, and you know I’ll have only your best interests at heart.”

His thespian talents should have made him a fortune. “As I said, Thurgood, I can’t make such a decision without consulting my very much alive and well husband. It’s good of you to call, but I must leave you for my domestic responsibilities.”

He affected his Wounded Look, which meant his You’ll-Regret-This speech was not far behind, and his frustrated rage not far behind that. Vivian ducked out, directing that Thurgood’s hat and coat be brought to him.

There was no squabble in the kitchen, of course, just as Thurgood hadn’t grieved the loss of Vivian’s mother for more than a few weeks before he’d been busy courting Ariadne’s predecessor up in Cumbria and trying to pawn Vivian off on some wealthy, desperate old lecher with no sons and fewer wits. Thank God, Muriel had offered employment, and thank God, William had a protective streak.

Which he seemed to have misplaced, or at least allowed to take an eccentric twist. Vivian reflected on that conundrum all the way down to Kent the next morning, wondering if William hadn’t concocted this scheme not for the continued glory of the House of Longstreet, but for her, to prevent her from becoming that poor relation at the mercy of Angie’s nursery or Thurgood’s next moneymaking project.

All too soon, she was being handed out of the coach by the object of her musings. Mr. Lindsey seemed larger than ever, but perhaps not quite as serious.

“My lady.” He bowed over her hand. “Welcome to Averett Hill. I hope your journey was uneventful?”

“Considering the roads are frozen and we could have snapped an axle at least a half dozen times, yes, it was uneventful.”

“Let’s get you out of this cold.” Mr. Lindsey drew her toward a tidy Tudor manor. “I have food and drink waiting, unless you’d like to see your rooms first?”

Vivian opted for the truth—several truths. “Something hot to drink sounds good. I sent William to Longchamps in the traveling coach, which means he got the hot bricks while I got the lap robes.”

“We can send you back to him in the relative comfort of my traveling coach,” her host replied.

She halted in her tracks. “Not if it’s recognizable, we won’t.”

His expression remained… genial. “There’s no coat of arms. I wouldn’t have made the offer of it if there were.”

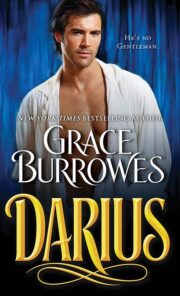

"Darius: Lord of Pleasures" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Darius: Lord of Pleasures". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Darius: Lord of Pleasures" друзьям в соцсетях.