“If I were to drive the little carriage,” said Mrs Annesley, “It could be useful to bring something to drink, and perhaps some sandwiches, for I think—am I not right?—that the countryside is quite remote, and there are no villages, no inns or taverns. And if any of the ladies are afraid of fatigue, one of them could take a seat with me, at any time, or ride with me for the whole of the way.” Anne immediately closed with the offer, and it was agreed that they should go together.

Chapter 10

The day dawned fine, with a gentle breeze. Anne's enjoyment was assured from the start by the knowledge that she was looking her best. It was Georgiana who had remarked that Anne never looked well in a bonnet. Neither close-brim, wide-brim, nor poke suited her small, delicate features; she merely looked “as prim as a governess,” said Georgiana. She had insisted on Anne trying on all her hats, and on giving her several. The one she was wearing today had been agreed by all to be the prettiest, with its wide, shady brim and green ribbons, and went very well with her new cambric gown.

So attired, she enjoyed the ride with Mrs Annesley, and a comfortable discussion of the evening gown she was to wear at the Lambton assembly. It was not too long before they came to the point where the carriage must be abandoned. Ahead of them they saw the rest of the party, who had begun to walk up a grassy path, to the actual face, and who kindly stopped to allow them to catch up. The ascent to begin with was not steep, and, everyone encouraging everyone else, was comfortably achieved. Soon their destination was before them, a steep, grayish line of rock, with the ground beneath it strewn with gray chippings and bits of stone. Here there was a short climb to a sort of rock shelf.

“I am afraid,” said Mr Caldwell, “that the best specimens have been taken out long ago. It is about twenty years since we were here, and many other enthusiasts have been here since then. But one never knows, there may be even better things still hidden.”

Georgiana was particularly interested, and getting up to quite a high point, soon called to Mr Caldwell, “Oh, sir! Do come! I am sure there is something very strange here! Do but look! These rounded shapes, these kind of stripes, are they not shells, or animals?”

“It may well be,” he replied, “but I cannot get up there to see; I am afraid I am not as young as I was. Here, Colonel Fitzwilliam, do you take my hammer, and get up there with her.” The Colonel obeyed, but the ledge where Georgiana stood was not large enough to hold them both, and she yielded up her place and started on the way down again.

“Dear me,” said Mr Caldwell. “I remember Darcy, scrambling up to that very ledge, and young Wickham, making his way up beside him, and saying 'Get out, Darcy, do, you have been up there long enough, get out, and let me try what I can do.' You must remember him well, Miss Darcy, for I know you always liked one another. I hear he is married. I hear he is to come back to the neighbourhood very soon—”

“No,” said Mrs Caldwell, “you are mistaken, my dear. It is young Mr Wicking, the churchwarden's son…” but as they were speaking, Georgiana, who had been carefully making her way down, suddenly seemed to twist herself away, and apparently misjudged her footing, for she slipped and fell.

There was a general outcry, and everyone ran to assist her. She had not fallen far, but she had fallen awkwardly, and appeared unable to rise. As Anne, who was nearest, got to her, she saw that Georgiana was crying, with heavy, gasping sobs.

“Oh, how bad is it?” Anne cried, and put her arms round her. Georgiana did not reply.

Mrs Annesley, coming up, said, “Come, Georgiana, come, my dear, let me see. Where does it hurt?” But Georgiana only cried out, and gasped. Mrs Annesley asked, “Does that hurt? Does that?” as she tried both her ankles.

“No, no, it is nothing, do not be concerned, I am well, it was only… I slipped. I am sure all is well,” Georgiana stammered, but as Mrs Annesley tried to help her to stand, she staggered, and would have fallen, but for her companion's arm.

Together, Colonel Fitzwilliam and Mrs Annesley got her seated on the grassy bank, while the others stood about, giving all sorts of suggestions, as people always do, and trying to think of anything useful they could do, when there was nothing. “I think she may have sprained her ankle slightly,” Mrs Annesley said. “I am sure that nothing is broken.”

“It seems unlikely,” said Colonel Fitzwilliam. “It was not a great fall, and she landed on the grass. I would be very surprised if any bones were broken. But what is best to be done now?” However, at that moment, Georgiana again tried to stand up, and this time she succeeded. She was a pitiful sight, with her face scarlet, and tears streaming down her cheeks; it was clear that the accident had distressed her very severely.

“We must take her home,” said Mrs Annesley.

“Yes, indeed,” said the Colonel. “Can she walk as far as the carriage, do you think? Or should we try to carry her?” Georgiana, hearing this, immediately—though not very clearly—intimated that she could walk. Holding tightly to Anne's arm, she proceeded to do so, and they arrived with little difficulty, though slowly, at the place where the pony carriage had been left.

Once she was safely placed in the carriage, Mrs Annesley turned to Anne. “I am afraid, my dear Miss de Bourgh, that we must abandon you,” she said. “If you would like, when we arrive I will send one of the grooms to drive you back to Pemberley. But for now, there is not room for a third person, and I must accompany Miss Darcy.” Anne, who had already come to this conclusion, lost no time in assuring Mrs Annesley that she would be quite comfortable walking back with the others, and the carriage drove off, amid the usual volley of good wishes and recommendations.

After this, nobody seemed to wish to spend more time at the face. Mrs Annesley, as a parting gesture, had handed out the basket with the food and drink, and having sat down in the shade of some rowan trees and refreshed themselves, it was generally agreed that they should start the walk back. The Colonel went ahead with Mr Caldwell, and Mrs Caldwell and her son accompanied Anne. After half a mile, Anne began to stumble.

“Do you find it very difficult to walk, Miss de Bourgh?” Mrs Caldwell asked.

“No… yes… a little,” Anne replied. “I am getting a good deal stronger, though I prefer to ride. The difficulty is that I have not been in the habit of walking very much, and have not the shoes for it. These shoes are not stout enough, and the soles do not keep the pebbles from my feet. “

“We can go as slowly as you wish,” Mrs Caldwell replied.

“Come, Miss de Bourgh,” said her son. “Do you take my arm. Is that better?” It was indeed: with the support of his arm, Anne could take some of the weight off her abused feet, and at once felt more comfortable.

“It is all downhill,” Mrs Caldwell said. “that makes it a good deal easier. See, we are almost at the park entrance already.”

“But there is another mile and a half to go,” Edmund Caldwell objected.

“Do not be concerned, I shall do very well,” Anne replied.

“It is a pity that you do not walk more,” he said. “It is always so: the more people walk, the more strength they have.”

“It is true, but at home, I was considered to be unwell. I only walked in the gardens, or went out in a carriage with my companion—the lady who looked after me. The walk to church, in good weather, was the farthest I ever got.”

“The way gets easier after the next turning,” Mrs Caldwell said. “Do you see that track to the right? The one that turns away just before the park gate, and winds up by the stream, among those rocks? That goes to Edmund's house. He does not live with us, you know; he has his own home.”

“It is three and a half miles from here,” he said, “up a very steep track, unsuited for carriages, and fit only for riding. I would not recommend you to walk up there, Miss de Bourgh. It is very hard. There is a carriage way up the other side, from Burley.”

“But perhaps we might make an expedition sometime; the house is worth seeing,” Mrs Caldwell said. “It is quite an historic place, though it is old and shabby, and he has never fitted it up properly, because he lives there as a bachelor.”

“It is true,” her son said. “I rough it in two rooms, and the rest of the house is pretty well empty.”

“And I think,” said his mother, “that he lives on bread and ham.”

“Oh, come, Mother, it is not so bad as that. Old Murray's wife is quite a good cook; they look after me very well.”

“It will be very pleasant when it is done up—and you will, sometime,” his mother said. “The rooms are all done up in the old paneled style, Miss de Bourgh, which they call linen-fold, and it is rather dark.”

“But I think you might like to see it, Miss de Bourgh,” her son said. “It was built by recusants—people who wanted to go on practising the old Catholic religion, in Queen Elizabeth's time. They wanted to live in a retired place, for their religion was forbidden. But they needed to see who was coming, and there is one room upstairs that has three windows, with views down several valleys. I have always thought it would be a wonderful room for a painter, or for an author to write in.”

“What happened to them?” Anne asked.

“Oh, they were ruined by the fines, for if people did not go to church, they were made to pay, so the queen got rich and they got poor. In the end, the house was sold and they went to live overseas, in France, and never came back.”

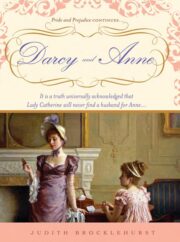

"Darcy and Anne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Darcy and Anne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Darcy and Anne" друзьям в соцсетях.