“I believe,” said Elizabeth, “that your cousin's wounds, and his courage, have had a great effect on her. There is a sort of chivalry in Georgiana. I think that she fell in love with Wickham, you know, because he represented himself as ill-used, neglected, and lonely. I talked with Colonel Fitzwilliam a little today—no! of course I did not mention my suspicions—but I am pretty sure that there is nothing on his side beyond the natural affection of a man for a younger cousin. He is a man of honour, and would never try to gain a young girl's affection for the sake of money. But it might make Georgiana unhappy.”

“Good heavens! What can I do? This place is his home, until he is fit to rejoin his regiment. I cannot send him away.”

“No, you cannot. The best we can do is to make sure that she has other choices, other interests. We have lived here, you know, very happily since we married, and, my love, I would wish for nothing more—but our comfortable, elegant family circle is very restricted. I believe that, for Georgiana, there should be a more varied society. In the ordinary way, she would have had a season in London, but as things are, we cannot give her that. Let us see how many things we can do to provide her with other people who she might admire or love. It could not be other than good for Anne, too.”

“We must go to the assemblies,” her husband said, “in Lambton and Burley. We have neighbours whom we can invite for dinner parties, and musical evenings. We can do much more than we have done. Summer is coming, there are race meetings, there are even cricket matches. I would see Anne more occupied, too—stay!—suppose we engage Georgiana, as an affectionate cousin, to help us with Anne? Would not that chivalry of hers be well engaged—to give Anne new interests and occupations—to look after her health— even to look for a husband for her?”

“Yes, indeed it would; it is the very thing. I will talk to her tomorrow.”

The morrow, for Anne, brought surprises indeed. She and her cousin Georgiana had a delightful drive around the park in Mrs Darcy's pony carriage. In the course of it, it transpired that Georgiana had an inordinate number of dresses, outgrown or outmoded, that only needed a little cutting down, and a few stitches, for Anne to be able to wear them. “And Anne dear, the Caldwells are coming soon, maybe next week. You must have something fashionable to wear!”

Anne was a little doubtful. What would her mother think of her wearing such thin, fashionable muslin gowns—she would call them flimsy and unseemly—as Georgiana was wearing?

“Oh, but everyone wears them,” said Georgiana firmly. “Do but try, let us go back to the house and try. It would oblige me so much, for I made several foolish purchases in London, and I have a green sprig muslin that does not suit me at all, and a dark blue silk, and I know that they would look pretty on you, and I would not feel so badly about having spent my brother's money; not that he cares, for he would buy me anything that I wanted. And you know, Anne, your mother need never know!” They did indeed look very pretty, even with the hems trailing past her ankles, and onto the floor, and the sewing maid promised to alter them as rapidly as might be.

Then Mrs Darcy's maid, who, it seemed, had very little to do, got at her hair, and created a new, very becoming style for her. Mrs Annesley offered to teach her to play the piano. Her cousin Darcy gave her the freedom of his library. And Colonel Fitzwilliam, quite unprompted, pointed out that Mrs Darcy could not, in her present circumstances, exercise her mare—such a gentle creature!—and offered to teach Anne to ride, thus raising Mrs Darcy's hopes quite considerably.

Chapter 9

The making over of Georgiana's clothes, for such a small lady as Anne, proved quite difficult, for Georgiana was sturdy as well as tall. However, Mrs Reynolds, the Pemberley housekeeper, got to hear of the matter. She had loved lady Anne Darcy, who had always been very well dressed, and thought it a great pity that her niece should be wearing unfashionable clothes that did not become her at all; the Pemberley ladies should be elegant! she produced several lengths of silk and muslin, bought at one time or another but never used. If Miss did not object to quite a simple style, she said, a couple of day dresses and an evening gown could be very quickly made up. And as for the style—yes! maybe in France, where they did nasty things, the ladies wore them with so little underneath that the unseemly creatures must surely catch their death, but Miss would see how comfortable such dresses were, and quite proper, with a nice thick English petticoat underneath!

The dresses were ready before the Caldwells arrived. Anne was delighted with them; they suited her well, and with her newly styled hair, she was able to play her part in the initial dinner party with a confidence she had seldom felt before. Visitors Came to Pemberley almost every day, and many had been very agreeable, but to see them again was so comfortable! She could talk with parents and son alike, with as much ease as if they were old acquaintances. Mr and Mrs Caldwell treated her like a daughter, and it was amazing how many of the same books she and Edmund liked!

The first evening, as they were all sitting together after dinner, Georgiana suddenly said, “Do you know, brother, that Anne says she cannot dance?”

“Not dance? Why, how is this?”

Anne admitted that she had, of course, been taught to dance, but being out of practice, unwell, and shy, she had not been able to the last time she was at a ball.

“That will not do at all,” said Mrs Darcy. “We are going to the Lambton assembly quite soon. What can be done?”

“If you would like, Madam,” said Mrs Annesley, “I would be very happy to play the piano, and we could walk Miss de Bourgh through a few figures, at any time.”

“Oh!” cried Georgiana, “let us dance now! We could make up, let me see… we are one… three… five women, and four men. We can make up three couples, if Mrs Annesley will play for us, and Anne can watch.”

“I have a better idea,” said Elizabeth. “I will play, you can make up four couples, and Anne can join in,” and she sat down at the pianoforte, and began a country dance.

It was strange, but after one walk through, Anne had no trouble at all in picking up the figures! Among friends, in whom she had confidence, her shyness vanished. She turned, and cast, and set, and curtseyed, and yet had leisure to notice that Colonel Fitzwilliam was by far the best dancer, and Edmund Caldwell the worst.

After this, they danced every evening. There were walks every day in the park, but soon everyone became ambitious, and a walk to the celebrated fossil face was proposed.

“How far is it?” Anne asked.

“I think it cannot be more than two miles,” her cousin Darcy said.

“A little more, I believe,” said Mr Caldwell. “Edmund, the fossil rock face—is it not about two miles distant from here?”

“I think so,” his son said. “It is a while since I walked it, and then it was from my own home; but I think it cannot be much more.”

“Two miles! Oh, that is nothing,” said Georgiana.

“Yes, but wait a moment,” her brother said. “It is not a ride, remember, you were talking of a walk.”

“Yes, but two miles, we walk almost that far when we go into the village.”

“But that is there and back.”

“Oh! I had forgot, we must come back.”

“Yes, but you will be coming downhill,” said Mr Caldwell.

“There is quite a steep uphill slope to get to the face.”

“It is all very well for most of you,” Mrs Darcy said, “but I confess that I have not, at this moment, such a burning interest in rock faces, as would lead me to walk four miles, in total, for the reward of seeing one. I think that I will be quite happy to stay at home.”

“And I will stay, and keep an eye on you,” Darcy said, “for I have some business matters that cannot well be put off. My steward has been looking at me reproachfully for several days now.”

Mr and Mrs Caldwell, however, were not to be held back, and constituted themselves the party's guides and principal mentors. “Indeed, my mother knows far more than I do,” Edmund Caldwell said. “And my husband knows more,” Mrs Caldwell said, “than both of us together.”

“I know very little of such matters,” said Colonel Fitzwilliam, “and my lack of knowledge embarrasses me; but if you will have me along, I will promise to be an attentive, if not an apt, pupil.”

Since arriving at Pemberley, Anne had gained a good deal of strength, but walking still fatigued her, and she much preferred to ride. Colonel Fitzwilliam was very pleased with her progress, and she delighted in her morning rides, which allowed her to see a great deal of the beauty of the park. She did not like to say that she was not up to a walk of four miles, but clearly, Colonel Fitzwilliam did not intend to go on horseback: suppose she started out, and could not complete the distance? Would she not be better advised to stay at home? Or would she be able to ride? Perhaps Georgiana or a groom would come with her? These thoughts had scarcely begun to occupy her mind, when Mrs Annesley proposed a plan. “that is too much of a distance for me,” she said, “but is the road fit for the pony carriage?”

“Perfectly,” Darcy said, “as long as the weather is fine. It is a pleasant country lane, except for the last few hundred yards, when you must leave the path, which is but a track by that time, and walk—or rather scramble—up to the face. We did it easily when we were boys, and even now it would not be too difficult for anyone wearing good stout shoes.”

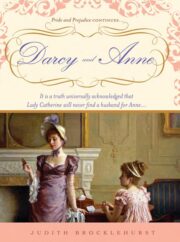

"Darcy and Anne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Darcy and Anne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Darcy and Anne" друзьям в соцсетях.