“And I think,” said Elizabeth, privately, to her husband, “that very few young women have gained a husband, by losing a fortune, but that is exactly what Anne has done. Who ever heard of such a thing?”

“You are right,” her husband said. “But I only fear that she may have done it very thoroughly.”

“Why, what do you mean?”

“I scarcely know; but I am not certain how secure her inheritance is.”

Chapter 27

The well-informed reader, aware that “The course of true love never did run smooth,” will not be surprised to perceive, from the thickness of the pages remaining, that Anne and Edmund did experience some further difficulties.

However, the initial few days of their engagement gave no hint of troubles to come. Then, one morning, several carriages drew up to the front of Pemberley.

“Oh,” cried Anne. “It is my dear Mr Bennet!”

Indeed it was, and with him, a handsome, rather over-dressed lady, with a slightly peevish expression, whom he introduced as his wife. Two young women, one pretty, one quiet and rather plain, were: “My daughters, Mary and Kitty.” From the second chaise there emerged a very sweet-faced young woman, bearing a strong resemblance to Elizabeth, and a good-looking young man, whom Darcy shook enthusiastically by the hand: “My friend Bingley.” But there was another lady, and Anne thought that Mrs Darcy's face fell slightly when she saw her, for this lady, though younger by far than Mrs Bennet, appeared equally peevish, if not more so. Could this be another sister? the extraneous vehicles contained such a supply of nursemaids, valises, and trunks, as may well be imagined, and Mrs Bingley, hastening urgently to one of them, demanded and received a small baby into her arms. It transpired that the unknown lady was not Mrs Darcy's, but Mr Bingley's sister, who had been quite unable to travel in the same carriage as the infant, owing to her extreme dislike of hearing a child crying.

The new house was ready, Mr Bingley explained, and they were on their way to it. “But you must have received my letter? I wrote to you, I did indeed, a week ago, that we had heard from the builders—the roof and chimneys are repaired, the house is habitable, and as for the new greenhouse, and the pinery, all that, you know, can be seen to far better when we are in residence. I wrote to you, at least a week ago,” but no letter had been received at Pemberley.

Not knowing that her family were coming, Mrs Darcy had invited the Rackhams, mother and children, and Sir Matthew and his mother to dinner. “And to keep the numbers even,” she said, “I asked Mr Kirkman, too, for now that I am not matchmaking any more, I find that I quite like him.”

“Well,” said her husband, “maybe we can find a use for him, for we must persuade someone to like Miss Bingley. He is a little older than she, but they might deal very well together.”

“How comes it,” Elizabeth asked, “that she is here? For I know she does not like me, and I am sure she has not forgiven you, for having the bad taste to marry me.”

“It seems that Mr Hurst has a sister who must be invited, with her husband, once in a while, and they asked poor Miss Bingley to vacate the spare bedroom for a few weeks, so the Bingleys had to bring her; and unless we can persuade Mr Kirkman to take a fancy to her, I do not know what we shall do. But you need not be concerned, my dear, for I am quite certain that Mrs Reynolds already knows how many people are arrived, and is making arrangements accordingly, and Forrest, too.”

“I am quite sure that they have, but I must go, all the same, and assure them both that I am perfectly astonished with all that they have done, and do not know what we should have done without them,” and Elizabeth, excusing herself to her guests, hastened away.

By dinner time, a mystery had been unraveled. Mr Bingley, on examining his travelling-desk, had found the letter, addressed and folded, that should have been sent to announce their incipient departure from Longbourn, and the probable day of their arrival at Pemberley. He recalled having no sealing-wax, and laying it aside until he should ask his wife for some. “And then, oh yes, Bailey came about the horses, and I went out to the stable yard with him, and I must have forgot.” By this time, however, rooms had been found and prepared for everyone, and in spite of, or perhaps because of, Mrs Reynolds's perturbation, the dinner was all that a Pemberley dinner ought to be.

Afterward they danced. Owing to the shortage of gentlemen, each of the ladies was sometimes obliged to sit down, and after an energetic country dance, Anne was glad to do so. She overheard Mrs Bennet ask Mrs Darcy, “But why is Miss de Bourgh to marry that very odd man? He is not rich, he is not handsome, and you tell me she could have married a Lord.”

“Hush, madam, pray hush, she will hear you.”

“Oh! nonsense, no one can hear in such a crowd. Well, if such a man as that is to marry into your family, and to be invited here, I do not see why you, and your husband, had to be so very nice about inviting poor Lydia. After all, she is one of us; she is your sister still, and he is your brother, and his brother, too.”

“But, the circumstances…”

“Oh, pooh; nobody cares about that; dear Wickham should not have run off with her, but much may be excused to a man in love, and they are safe married now. Lydia is in poor health, for she is expecting an interesting event, as I told you, and their lodging is not commodious or comfortable. I do think it is hard that she is not to come, for a spell at Pemberley, with her sisters, would have raised her spirits, and improved her health. And dear Wickham talks a great deal about his childhood home, and I am sure he misses it very much. Why should you not all be reconciled, pray? If you and Mr Darcy are ashamed of her, you must be ashamed of us, too.”

This was perhaps the first time that Mrs Bennet and her daughter had had a serious conversation since Elizabeth's marriage. But Mrs Darcy was no longer the unmarried and not-much-loved daughter, who must treat a parent with respect and deference. She answered with the authority of a married woman, with a home, husband, and child of her own. “I am sorry, madam; but I cannot invite her. For one thing, I do not think she would do well at Pemberley, for you know how noisy and indiscreet she is. But even if I did wish to invite her, it cannot be. I could not ask her without asking her husband, and Mr Darcy will not permit it; he will not receive him.”

They moved away, leaving Anne puzzled and surprised. To refuse to invite a sister, who was not at all wealthy, and not well! It seemed so unlike the new, kind cousin whom she had begun to know! She turned and found Georgiana standing beside her. Mrs Bennet, who might, Anne thought, be becoming slightly deaf, had spoken pretty loudly, and she could see clearly, from Georgiana's expression, that she had heard, too.

“You think my brother unkind,” Georgiana said.

“I do not understand,” Anne said. “It is not like him, or Elizabeth. They are so generous, they have been so welcoming to me, though I am but a cousin and might be thought to have far less claim on their hospitality. It disturbs me that these people seem unwelcome here, because they are poor and of lower rank than I.”

Georgiana drew a deep breath. “I can explain,” she said, “and I will. I cannot bear it, that you should think my brother ungenerous. But I cannot tell you now. Come for a walk with me, come tomorrow morning; the men will all be out shooting—yes, Edmund too, for I heard him tell my brother that he should go—and we can be private.”

Chapter 28

THE NEXT MORNING, THEY WALKED OUT TOGETHER, AND WENT up the stream, whose deep, secluded valley was the chosen spot for every quiet conversation, every confidence. As soon as they were out of sight of the house, Georgiana began: “What I am going to tell you now, Anne, I have never spoken of to a soul,” she said. “My brother knows of it, and Elizabeth knows some of it, but no one else. I know I can rely on you to mention it to no one.”

“Of course,” Anne said. If secrecy meant so much to Georgiana, then clearly even Edmund could not be told.

“This happened a few years ago,” Georgiana began, “before my brother was married. Both my parents had been dead for some years, and I was at a school in London. My brother sometimes came to see me, but a young man has not often very much time for visiting a younger sister; and I missed my dear mother so very much.”

“My father and I were very close,” Anne said. “I know what it is, to mourn a beloved parent.”

“When I was fifteen,” Georgiana continued, “I was judged old enough, or accomplished enough, anyway. I was thought ready for life, for I could play the piano very well, and the harp a little, and paint, and could speak French and read Italian. No one gave any thought to the fact that I knew nothing of my own feelings, or of my own nature. Since my brother was not married, an establishment was set up for me, and a lady was hired to take care of me: that is, to see to it that I was fashionably dressed, and to take me into company. She was lively and gay, and if some of the sentiments she occasionally expressed seemed not very proper, she was amusing, and I thought it a part of fashionable life. She would tell small lies, and laugh, and recount improper stories—but again, very amusingly, so that the impropriety seemed not harmful, and it would seem prudish to object. Her taste in clothes was excellent; I liked her, though I did not love her; we saw something of my brother from time to time, and I did not think myself unhappy.

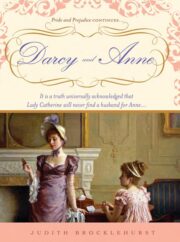

"Darcy and Anne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Darcy and Anne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Darcy and Anne" друзьям в соцсетях.