Then, to Anne's surprise, he spoke of “Miss Lucas.” It was a few moments before Anne realised that he was speaking of Mrs Collins. “I do not know her well,” she said, timidly, for she had always avoided entering the Parsonage, whenever the carriage stopped there, disliking Mr Collins' servile and ingratiating ways.

“She is a very brave and sensible woman,” Mr Bennet said, abruptly. “Did you know that my Lizzie was supposed to marry that fool, Collins?” Anne did indeed know; she had heard her mother speak on the subject, many times, and ask, why had not the presumptuous Miss Bennet become the parson's wife, and stayed within her station in life, where she belonged?

“But she turned him down, thank God,” said her father, “and then poor Miss Lucas turned round, in the twinkling of an eye, and snapped him up. She had not a hope of marriage, but was all set to die an old maid; she may be said to have got him, as they vulgarly say, on the rebound, but she got him. And she has made something of it, that is the remarkable thing. My daughter tells me that she writes with pleasure and enthusiasm of her home, her garden, her occupations, and now her child; and then, too, she has made Collins a happy man, or as happy as such a stupid fellow can be. That, Miss de Bourgh, is what I call courage. We most of us have to make some sort of adjustment to our lot in life; we mostly have to cut our coat to suit the cloth. But for my Lizzie it has not been so; they have found each other, and it is truly a marriage of like minds. He understands her worth. But oh, can you not see, what a ruin, what a desolation it would be, if Elizabeth were lost to us?”

Anne was horrified. She took a deep breath: “Come, sir, there is no need at all to be thinking of such a contingency. Your daughter is a strong, healthy, young woman, this is her first child, and she is receiving the best attention that it is possible to have. Daughters often resemble their mothers in these matters. You have just told me that her mother had five children, and, if I understand you aright, is still in very good health. There is no reason at all for imagining such a thing. There may be some anxiety about the child, but many eight-month, and even seven-month babies live, and do well. Truly, my dear Mr Bennet, I cannot allow you to think of such a thing. Your concern is due to your affection for her, and does you credit, but forgive me, are you not allowing your imagination to run away with you?”

“Well, you may be right. I hope you are right.”

“Of course I am right! Come, Minette is trying to chase the squirrels again; come and watch her, foolish little thing.”

Back at the house, Mrs Annesley had gone to see Mrs Reynolds, who had somehow convinced herself that both mother and child would die, and was sitting weeping in her room. Mrs Annesley told her firmly to stop crying, for she was needed, and asked her whether anybody had considered that a wet nurse might be wanted.

“Oh no, madam, Mrs Darcy would not think of such a thing, she said she wanted to nurse the child herself—they do nowadays. Lady Anne Darcy always had one, and Lady Catherine too; but times have changed, madam, have they not?”

“Yes, indeed, but I think that it should be thought of, for Mrs Darcy may not be well, things are not just as they ought to be; she may be very exhausted after the child's birth. Tell me, Mrs Reynolds, you know most of the people in Lambton, do you not?”

“Oh, yes, madam, I have lived here all my life.”

“Well, I want you to consider, and to ask the other servants as well, whether there is any young woman who could come, for I think someone may be needed.”

Mrs Annesley's conviction that mother and child were expected to live, and the thought that she herself was wanted and could be useful, worked powerfully on Mrs Reynolds. She dried her eyes, and set to thinking: She knew of the very person! A young woman living only three miles away, very clean, healthy, “…and she is a Methody, all the family are, and go to the chapel, which I cannot like, but it is all for the best, for they never touch liquor, or even beer.” She would at once send to Torgates Farm, and set about making the necessary arrangements; oh yes! the young woman would come if she were needed, anybody would come, to help Pemberley.

Mrs Reynolds' restoration to her usual self quickly restored the spirits of the other servants. “Servants always go to pieces,” Mrs Annesley said, “if the person in command is suddenly removed. I told them that Mrs Darcy, when she is up and about again— when, not if—will expect to find that everybody has done their duty, just as if she were there. They are all very fond of her, which helps, and everything was right, once the cook knew what was wanted for dinner, which he could perfectly well have thought of for himself.”

Shortly before midday, the gentlemen returned with Dr Lawson. Darcy looked better for his ride, and everyone felt convinced that now things would soon be right. But there was no news, and the afternoon seemed very long. The Rector of the parish came to visit, and was admitted. He was an intelligent, gentlemanly, serious-minded man, to whom Darcy had recently presented the living, saying that he did not want a man who would flatter and obey him, but one who would take care of the people. He sat with them quietly for some time, and then left. Anne did not think that his presence had helped anyone very much, for he was not a man of optimistic mind, and could not hide the fact that he did not know if he would next be called upon to baptize, or to bury.

A little later, Anne proposed that they might attend the evening service, at the church. Mrs Annesley said she would go; Colonel Fitzwilliam wanted to go with them, but did not know whether he should leave Darcy; however, Mr Bennet quietly offered to take Darcy on at a game of chess, or walk with him, whichever he might prefer.

When they got to the church, it was surprisingly full. It seemed that many of the people of Lambton had had the same thought, and as they entered, there was a murmur of quiet sympathy. As they made their way forward to the Darcy pew, Anne saw Georgiana, and with her, Mr Rackham, his mother, and Mary.

The ancient words of the Prayer Book were comforting. Anne felt sorry that it was not the day or time for the Litany, for one phrase was certainly in everyone's mind: the words “for all women labouring of child.” As they left, people crowded round in silence; some pressed Mrs Annesley's hand. Anne felt glad of their kindness, but understood why Darcy had not wanted to come.

Georgiana returned with them. Dinner was a miserable affair; the cook might as well not have troubled himself, for very little was eaten. When it ended, the gentlemen did not stay behind, but went straight to the drawing room with the ladies. Darcy made for an armchair and sat, his head in his hands.

“I will ring for tea,” Mrs Annesley said. “It will do us good. Oh, Forrest, there you are, I was just going to ring…”

But it was not the butler. Dr Lawson stood in the doorway.

“Mr Darcy,” he said. Darcy looked up at him. Anne thought, This is how my cousin will look, when he is old.

“Mr Darcy, sir, you have a son.”

Chapter 20

“He is a fine young fellow,” Dr Lawson said. “A little small, but that was only to be expected; however, there is nothing to worry about, he has every intention of living, and so has his mother. She is sleeping; you may go to her, sir, but you must not speak to her, do not be trying to wake her up. You will have all the time in the world to talk to her, later.”

Elizabeth was safe, and she had a son! Anne thought that she had never before experienced such felicity. She and Georgiana threw their arms around each other. She saw tears running down Mr Bennet's face; she thought she saw Colonel Fitzwilliam kiss Mrs Annesley; then she burst into tears herself. Darcy disappeared upstairs. They had recovered their composure somewhat by the time he came down, accompanied by the nurse. She was carrying a swaddled bundle, which contained Lewis Bennet Fitzwilliam Darcy. Her father's name! they had given him her father's name!

Mr Bennet, now quite himself again, looked cautiously at the infant, and observed that he looked very small for such a colossal collection of names. Then Georgiana said, “Oh, my goodness, I am an aunt!” With the child's birth, she had become that happiest and most useful of human beings, an aunt! After the tears, there was laughter; the butler brought wine, and the cook sent up sandwiches and soup, for everybody was suddenly very hungry. Then someone—she thought it was Mrs Annesley— said “Oh, listen!” They all went to the French windows of the drawing room, which were open, for it was a fine, warm night. The church bells were ringing.

The next few days passed in a happy blur of visitors, letters, messages and congratulations. However, they also brought two things to Anne herself that were very welcome. First of all, three new dresses were delivered—three dresses that she had decided on, and ordered, and paid for herself. Hardly had she recovered from the pleasure of trying them on, and finding that she looked delightfully in them, than her cousin came to find her; there was a letter for her.

“It must be from my mother,” she thought. But it was not; it was from Mrs Endicott. Mrs Caldwell, it appeared, had read Anne's manuscript to her and her husband, and they were much impressed with it. They both believed that the story, entertaining and lively, would appeal strongly to the public. They hoped very much that Anne would finish the story, and if she were to think of publication, would she do them the favour of discussing the matter with them, before approaching anyone else?

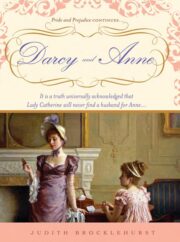

"Darcy and Anne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Darcy and Anne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Darcy and Anne" друзьям в соцсетях.