When Godolphin presented himself to Anne and she expressed her wishes that John Hill should become a colonel he assured her of the impossibility of this.

“My lord Marlborough will explain to Your Majesty why this cannot be.”

“I see nothing but frustration,” cried Anne. “It seems that you, sir, work continually against me.”

Godolphin with tears in his eyes protested, but the fact that she could not grant Abigail one of the few requests she had made, hurt Anne. A colonelcy in the army! It seemed such a small thing to ask—and it was so natural that Abigail should want it for her brother. Yet she, the Queen, was not allowed to make it.

Godolphin left in despair.

Marlborough called on the Queen, who regarded him coolly.

“Your Majesty,” he said, “my enemies have distorted my action and I fear I have been greatly misrepresented in your eyes.”

Anne bowed her head and stared at her fan.

“I want to have a chance to clear myself of the calumnies of my enemies.”

“Pray proceed,” said the Queen.

“There is a charge against me that I made an attempt to become a military dictator of this country. That is false.”

The Queen did not answer. Had he not come to her himself and asked for the Captain-Generalcy for life? What else did that mean? Oh, she was weary of these Marlboroughs!

She put her fan to her mouth. It was a gesture implying that she wished to hear no more on that subject. In her opinion he had attempted what he denied and by great good fortune—and the services of good men like Mr. Harley—he had been prevented.

Marlborough turned the subject to the proposed colonelcy for John Hill.

How much he wished to please Her Majesty she herself knew. The fact was that there were old soldiers in his Army who had served through many battles—deserving men. It was a commander’s chief duty to keep his men happy. If favours were bestowed on men because of their charming relatives this was bad for the Army.

“Madam,” he said, “we have won many great victories but we are not yet at peace. I cannot endanger the future of this country by making discord in the ranks. This would most certainly happen if a high command were given to an inexperienced soldier when veterans were overlooked.”

“So you will not give this colonelcy to Hill?”

“Madam, I would resign my post rather than do so.”

He bowed himself from her presence.

She was not a fool. At least on this point he spoke good sense. She would not give up, of course; but it seemed as though Abigail’s brother might have to wait until he was a little more experienced before he received promotion.

Abigail was disconsolate because she had failed to give the colonelcy to her brother; but she believed that this was a small matter compared with the great victory which was just in reach.

She was certain that very soon the Godolphin–Churchill Ministry would be defeated and Robert Harley’s set up in its place.

The Duke of Marlborough was preparing to leave for Flanders for the spring campaign and came once more to the Queen before he left.

Anne was gracious to him, for she had always had a fondness for him, and even when she felt him to be most dangerously arrogant he was always charming.

“I have come to speak to Your Majesty on behalf of the Duchess?” said Marlborough, and immediately noticed the stubborn set of the Queen’s lips. “She wishes to remain in the country a great deal and asks that her posts may be bestowed on her daughters.”

Anne was relieved. “This should be so,” she said, and her relief was obvious. Anything, she was implying, to be rid of Sarah.

The Duke took his leave and Sarah arrived to thank the Queen for bestowing honours on her family.

Anne listened, in silence, and when Sarah asked if there had been some misunderstanding, she replied, “There has been none. But I wish never to be troubled more on this subject.”

Sarah opened her mouth in protest. But Anne repeated that she did not wish to be troubled more on the subject.

Sarah knew that she was defeated.

For once she had nothing to say.

Marl was going away once more; and now everything depended on the outcome of the trial of Dr. Sacheverel.

Abigail was alarmed. She realized now that she was in the forefront of the battle for power. At last her importance had been recognized. Not only was it known that she had ousted Sarah Churchill from her place in the Queen’s affections, but she had allied herself with Robert Harley, making it possible for him to have many an intimate interview with the Queen, so that now there was consternation in the Whig Ministry—for the Queen had the power to dismiss Parliament—and it was realized that the trouble could be traced to one who had seemed to be nothing more than a humble chambermaid.

First it was a whisper, then a slogan; and after that it was a battle cry: “Abigail Masham must go.”

The Earl of Sunderland, Marlborough’s son-in-law, always inclined to rashness, declared that nothing must be spared to banish Abigail Masham from the scene of politics. His plan was that Marlborough should give the Queen an ultimatum: either Abigail Masham left the Queen’s service or the Duke of Marlborough would.

There was a conference at Windsor Lodge, presided over by Sarah.

“It is too risky,” said Marlborough. “What if she should choose Masham.”

“And disrupt the Army!” cried Sarah.

Marlborough looked tenderly at his wife; and even as he did so he thought how different everything might have been if she had not lost the Queen’s favour by her own rash outspokenness, and her inability to see another point of view than her own. But how could he blame Sarah? He loved her as she was. Had she been sly like Abigail Masham she would not have been his dashing flamboyant Sarah.

“We have powerful enemies,” he reminded her.

“Harley. St. John—that cabal … and of course whey-faced Masham.”

“The Queen cannot afford to lose you,” Sunderland reminded his father-in-law. “She will have to give way.”

Godolphin, feeling tired and each day growing more and more weary of political strife, believed it was an odd state of affairs when a government must concern itself with the dismissal of a chambermaid. But he was too tired to allow himself to protest.

“At least,” said Sarah, “we did not allow Masham’s brother his colonelcy. It shows that we only have to take a firm stand.”

She laid her arm on her husband’s shoulders. “I will have Brandy Nan recognize your greatness however much she tries to shake her silly head while she gabbles her parrot phrases.”

Godolphin looked a little shocked to hear the Queen given such an epithet; but Sarah and Sunderland won the point and Marlborough was induced to write a letter to the Queen pointing out that she must either dismiss Mrs. Masham or himself.

Robert Harley was a man who liked to work in the shadows and had spies concealed in all places where he believed they could serve him best. Even as Marlborough was writing his letter to the Queen news was brought to him of what it would contain.

Abigail or Marlborough. It would be a difficult choice; for although Marlborough would not be accepted as a military dictator of the state he must undoubtedly remain Commander-in-Chief in Europe until a satisfactory peace had been made.

Harley called on Abigail and as a result Abigail went to the Queen.

Anne knew at once that something was worrying her favourite as soon as she saw her.

“The baby is well?” she began.

Abigail knelt before Anne and buried her face in the Queen’s voluminous skirts.

“They are trying to part me from Your Majesty,” she cried.

“What!” cried Anne, her mottled cheeks turning a shade less red, her dulaps trembling.

“Yes, Madam. Marlborough is going to offer you a choice. Either I go or he does.”

“He cannot do this.”

“He will, Madam. I have heard that he has already written the letter and that it is only because Lord Godolphin is a little uncertain that it has not yet reached you. The Duchess and Lord Sunderland are in favour of it and … it will not be long before they have persuaded Godolphin.”

“I shall not let you go.”

“Madam, they may make it impossible for you to keep me.”

“Oh dear,” sighed Anne. “What troublemakers they are! Why should they wish to part me from my friends!”

She was agitated. Lose Abigail! It was impossible. And yet these clever men with their devious ways were trying to drive her into a corner.

“There is no time to waste,” she said. “I will send for Lord Somers at once and tell him how kindly I feel towards the Duke of Marlborough and how I hope that I shall soon have an opportunity of demonstrating my affection for him. At the same time I will tell him that I will never allow any of my ministers to part me from my friends.”

Abigail looked up into the Queen’s face and seeing the obstinate set of the royal lips was reassured.

Godolphin paced up and down the chamber at Windsor Lodge.

“It’s no use,” he said, “she’ll never give up Masham. You can be sure that our enemies abroad are getting the utmost amusement out of this situation. The Government versus a chambermaid. It is making us ridiculous.”

Marlborough saw the point as Sarah would not. It was for this reason that Godolphin had chosen a moment to speak to the Duke when he was alone.

Ridicule could be a strong weapon in an enemy’s hand. In war an Army needed to have as many points in its favour as could be seized; and none was too small to be ignored.

Godolphin was right; Sarah and Sunderland were wrong. This battle between a Commander-in-Chief of an army and a chambermaid must not be allowed to become a major issue.

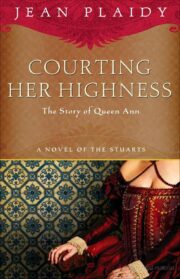

"Courting Her Highness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Courting Her Highness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Courting Her Highness" друзьям в соцсетях.