He looked quite thunderstruck. “Are you telling me, Kitty, that this is why you are here, and sent me so urgent a message that I found myself constrained to respond to it, in spite of the fact that my leaving Biddenden in such haste put my brother and his wife to considerable inconvenience? I went to Biddenden upon family affairs of some moment, and all must be at a stand until I return there.”

“Well, I am sure I am very sorry, Hugh, but you may return as soon as you have performed your part here, you know!” said Kitty reasonably.

“That,” he said, “I am by no means inclined to do! I do not know under what circumstances Dolphinton has contracted his engagement, but it is plain to me that it is not one of which my aunt would approve. You would not else be here! I cannot lend myself to anything that savours of the clandestine.”

“Hugh!” gasped Kitty. “I had thought you poor Dolph’s friend!”

“I am his friend, as I hope he knows.”

“You cannot be, for you would not stand there talking in that heartless way if you were! Dolph and Miss Plymstock love one another!”

Miss Plymstock, who had been stolidly staring at the Rector, interposed, to say bluntly: “Seems to me it ain’t in your power to refuse to marry us, sir, for all this fine talking. Foster’s of age, and so am I. You’re thinking, I daresay, that I ain’t good enough for your cousin. Well, I don’t pretend to be any better born than what I am, but what I do say is that I shall make Foster a better wife than many a one that has a title.”

“Yes, you are good enough for me!” said Dolphinton. “I won’t let you say you ain’t. Won’t let anyone say it!”

“That’s right, Dolph!” said Kitty approvingly.

Emboldened by this encouragement, his lordship went further. “I won’t let Freddy say it, and I like Freddy. Like him better than Hugh. If Hugh says it, I’ll draw his cork. Do you think I should do that, Kitty?”

“Well, I don’t precisely understand what it means, Dolph, but I daresay it would be an excellent thing to do.”

“Lord, my dear, it don’t matter to me what anyone says of me!” said Miss Plymstock. “Let ’em say what they choose, for it won’t vex us. Don’t you start picking a quarrel with the Reverend! He’s bound to think you’re marrying beneath you, for I can see he’s a proud kind of a man; but maybe, if he likes to come and visit us in Ireland, he’ll own he was mistaken.”

Dolphinton’s face brightened. “I should like Hugh to visit us. Like Kitty to visit us. Like Freddy to visit us too. I shall show them my horses.”

Kitty took advantage of this interlude to pull the Rector over to the window, and to say to him in an urgent under’ voice: “Hugh, upon my word I promise you that you cannot do Dolph a greater service than to marry him to Hannah! She is the kindest, most practical creature! She means to take him to Ireland, and let him breed horses, so that he may be perfectly happy and busy. You must own it would be the very thing for him!”

“Certainly, I have always been an advocate for his living quietly in the country. It is noticeable that whenever he has been staying here with me he is perfectly rational. I do not say that his intellect is strong, but he is by no means an imbecile.”

“Indeed, he is not! But are you aware, Hugh, that his Mama threatens to have him locked up?”

He cast a quick glance over his shoulder, but Dolphinton was engaged in enumerating to Miss Plymstock the various attractions of his Irish house. “You must be mistaken! She could not do such a thing. It is quite unnecessary.”

“I don’t know what she is wicked enough to do, but I do know that that is what terrifies poor Dolph so. As for that doctor of hers, Dolph is thrown into a quake whenever he thinks about him. Why, she even sets his servants to spy on him! He told me so himself, and how they tell her all he does, and where he goes!”

“You shock me very much!” he said. “I had not believed it to have been possible. But to be eloping in this fashion, and to expect me to abet him in conduct which is quite improper—”

“I see what it is!” she interrupted, a sparkle in her eye. “You are afraid to do it! You are afraid of your aunt, and of what people may say! I think it very poor-spirited of you, Hugh, but I am very sure it is not in your power to refuse to marry two persons, when there is no—no impediment!”

He said, flushing a little: “There is no occasion for you to speak with such unbecoming heat. I am certainly not afraid to do what I conceive to be my duty. But in this instance there are considerations of family involved, which—”

“If Freddy does not regard such considerations, I am sure you need not!” she interrupted.

He looked rather taken aback. “Does Freddy, then, know of this affair?”

“Yes, indeed he does!”

“I can only say that I am surprised. However, I cannot allow Freddy to be a guide to my conduct.”

She was stung by his tone of superiority into retorting: “I do not know why you should not, for he is a Standen, after all!”

At this moment, Miss Plymstock touched Kitty’s arm. “Beg pardon, but I’ll be glad to know what you have decided,” she said. Sinking her voice, she added: “It won’t do to be keeping Foster in suspense, for he’s had a very exciting day, which ain’t good for him.” She glanced from Hugh’s rigid countenance to Kitty’s angry one. “I collect you don’t mean to oblige us, sir,” she said. “Well, if you won’t you won’t, but I’ll tell you to your head I’ll not let Foster go back to be driven crazy by his mother. If I’m driven to it—though I own it ain’t what I like, partly because I was reared to be respectable, and partly because it don’t put me in a strong position when it comes to dealing with her ladyship—I’ll take Foster away, and live with him as his mistress until I can find a parson that will marry us.”

The Rector looked down from his impressive height into her homely but resolute countenance, and said stiffly, and after a moment’s pause: “In that event, ma’am, I am left with no alternative. I cannot perform the ceremony at this hour, but if you will have the goodness to show me the licence, I will marry you to my cousin tomorrow morning.”

A stricken silence greeted these words. Both ladies stood staring up at him. “L-licence?” Kitty faltered at last.

“The special licence to enable persons to be joined in wedlock without the calling of banns,” explained the Rector. “Surely, my dear Kitty, you were aware that this is necessary for what you propose I should do?”

“I have heard of special licences,” she said. “I didn’t know—I thought—Oh, what have I done? Hannah, I am so very sorry! I ought to have asked Freddy! He would have known! I have ruined everything!”

“It’s my blame,” said Miss Plymstock gruffly. “The thing is we’ve never had anything but banns in my family, and it slipped my mind.”

Kitty turned, laying a hand on the Rector’s arm. “Hugh, it can’t signify! You would not stick at such a trifle as that!”

“If you have not obtained the necessary licence, it is quite out of my power to perform the ceremony,” he said.

Lord Dolphinton, who had been trying to follow this, now joined the group by the window, plucking at Miss Plymstock’s sleeve, and demanding: “What’s this? Does he say I cannot be married? Is that what he says?”

“I am sorry, Foster, but unless you have with you a special licence it is impossible for me to marry you.”

His lordship uttered a moan of despair. Miss Plymstock drew his hand through her arm. “Don’t you fly into a pucker, my dear!” she said calmly. “We shall find a way to brush through it, don’t fear! We—”

She broke off, for the door had opened, and a beam of lamplight shone into the darkening room. Mrs. Armathwaite came in, carrying a lamp, which she set down upon the table, saying: “I’ve brought the lamp, sir, and there’s no need for you to worrit yourself about dinner, for it happens that we have a nice shoulder of mutton, which I’ve had popped into the oven, and a couple of spring chickens, which will be on the spit in another ten minutes. Good gracious, what ails his lordship?”

Dolphinton, in the act of disappearing into the cupboard beside the fireplace, paused to say in anguished tones: “Not here! Not seen me!”

Kitty, who had also heard the sound of a vehicle drawing up, peered out into the dusk. “Dolph, don’t be afraid! It is not your Mama! It is only some gentleman—why—why, I do believe—It is Jack! Good God, what can have brought him here? Oh, I am persuaded he will be able to help us! What a fortunate circumstance! Come out, Dolph! it is only Jack!”

Chapter XX

In a very few moments, Mr. Westruther, admitted to the house by Mrs. Armathwaite, strode into the Rector’s parlour, and stood for a minute on the threshold while his keen, yet oddly lazy eyes took in the assembled company. They encountered first Miss Charing, who had started forward into the middle of the room. An eyebrow went up. They swept past the Rector, and alighted on Miss Plymstock. Both eyebrows went up. Lastly, they discovered Lord Dolphinton, emerging from the cupboard. “Oh, my God!” said Mr. Westruther, shutting the door with a careless, backward thrust of one hand.

The Rector’s parlour was of comfortable but not handsome proportions, and with the entrance of Mr. Westruther it seemed to shrink. The Rector was himself a large man, but he neither caused his room to dwindle in size, nor seemed out of place in it. But he did not wear a driving coat with sixteen capes, which preposterous garment added considerably to Mr. Westruther’s overpowering presence; he did not flaunt a spotted Belcher neckcloth, or a striped waistcoat; and if the fancy took him to wear a buttonhole, this took the form of a single flower, and not a nosegay large enough for a lady to have carried to a ball. He had a shapely leg, and took care to sheathe it, when he rode to hounds, in a well-fitting boot; but he despised the white tops of fashion, and his servant was not required to polish the leather until he could see his own reflection in it.

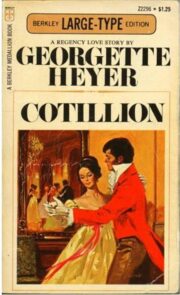

"Cotillion" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Cotillion". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Cotillion" друзьям в соцсетях.