“Lord, Meg, I should have thought you might have prevented her!” exclaimed Freddy, quite disgusted. “Easy enough to have hatched up an engagement, and said you depended upon her to be at home that evening! I’ll tell you what it is: you’ve a deal more hair than wit!”

“Oh, well!” Meg said, looking a little conscious, “I could not do that, as it chances, for I am going out myself that evening. One of Buckhaven’s old aunts: I would not subject Kitty to her odious, quizzing ways for the world!”

Freddy looked suspiciously at her, but she was rearranging her scarf, and did not meet his eyes. “Sounds to me like a hum,” he said.

“Good gracious, why should it be?”

“Don’t know. Thing is, know you! Well, stands to reason! Bound to! However, Kit ain’t likely to get into a scrape, dining in Hans Crescent. Come to think of it, might serve pretty well. You ever seen those Scortons, Meg? Well, I have! Nothing but a parcel of vulgar dowds! Very likely to give Kit a distaste for the whole business. Don’t you go kicking up a dust!”

So, on the appointed day, the Buckhaven town-coach conveyed Miss Charing to Hans Crescent; and when the coachman asked her at what hour she would wish him to call tor her again, Mr. Thomas Scorton, the son of the house, informed him that he would charge himself with the agreeable duty of conveying Miss Charing to Berkeley Square. She demurred a little, but was overborne, Mr. Scorton telling her, with a wink, that they had a famous scheme arranged for the evening. She was obliged to acquiesce therefore, and to allow herself to be ushered into the house. Here she was met by Olivia, who led her upstairs to take off her cloak, chattering all the way. Kitty knew already that Mrs. Broughty was spending a night at her own home, but she was scarcely prepared for the rest of Olivia’s news. Olivia, whose eyes were shining like stars, told her that her cousin Tom had been so obliging as to hire a box at the Opera House, for the masquerade, and that her dear, dear Aunt Matty had said that if they were all determined to enjoy a frolic she would escort them, for she knew what it was to be young, and in her day she had hugely loved a frisk of this nature.

“And, oh, dear Miss Charing, was it dreadfully fast of me?—I wrote to your cousin the Chevalier, telling him that we hoped for the honour of your company, and asking him if he would go with us. And he is even now talking to my aunt in the drawing-room! Oh, have I done amiss?”

“No, no, but—a masquerade! I am not dressed for a ball. And if it is a masquerade, should one not be dressed in character? I wish you had told me earlier, Olivia!”

“Oh, it doesn’t signify! None of us mean to wear historical costumes, but only dominoes and masks, and I have procured a domino for you, my aunt warning me that very likely you would not be permitted to go with us, if Lady Buckhaven knew of it. She says that members of the high ton despise these masquerades amazingly. I knew you would not care for that! We shall be masked, of course, and no one will know us.”

Kitty recollected that a mask and a domino had been her only disguise at the Pantheon masquerade, and was satisfied. She would have preferred not to have gone to a large ball under Mrs. Scorton’s chaperonage; but she felt that she was perhaps refining too much upon trifles. A refusal on her part to go to the Opera House must necessarily break up the party, and spoil Olivia’s pleasure. She schooled her countenance to an expression of gratification, and secretly hoped that she would not be obliged to dance very frequently with Tom Scorton.

As the two ladies descended the stairs to the drawingroom on the first floor, Olivia said, shyly, but as though sudden happiness made it impossible for her to resist a little gush of confidence: “Do you know, Miss Charing, it is the most absurd thing, but I fancied—that is, I had an apprehension —that something had occurred to vex the Chevalier? He had not visited us for such an age! At least, it was only ten days, of course, but I supposed—I was in the expectation—

But it was all nonsense, for he was very glad to come tonight. You will say I am a goose!”

Kitty, who was preceding her down the stairs, looked back, saw her blushing, and said laughingly: “No, but do, pray, tell me! Have you fallen in love with Camille? I could see, upon his first setting eyes on you, that he was very much struck, I assure you! When must I v/ish you happy?”

Discomposed, Olivia turned away her face, faltering: “Do not—! It would be so very unbecoming in rne—! He has not spoken, and if I thought that he might do so, lately I have been afraid, when there seemed to be no continued observance, that I had imagined the whole, or—or perhaps that he felt I was not grand enough!”

“If he is such a coxcomb as that, you would be very well rid of him!” Kitty replied.

“No, no, how can you say such a thing? So perfectly the gentleman! Indeed, I am fully conscious of the difference in our stations—scarcely dared to entertain the hope that his affection was animated towards me, as mine, dear Miss Charing, was animated towards him!”

They had by this time reached the landing, and there was no opportunity for further discussion. Kitty, with the uncomfortable recollection in her mind of having on a number of occasions observed her cousin dancing attendance on Lady Maria Yalding, could not but be glad of it. Olivia opened the door into the drawing-room, a babel of voices smote their ears, and Kitty entered to find the rest of the party already assembled. It so happened that the Chevalier was seated in a chair that faced the door, and as Kitty paused for an instant, looking for her hostess in what seemed to be a crowd of persons, he glanced up, his eyes alighting upon Olivia. There was no mistaking the ardent expression that sprang to them, or the tenderness of the smile which touched his lips. The next moment he was on his feet, and was bowing to his cousin. She smiled, and nodded to him, and moved forward to greet Mrs. Scorton, who had surged up from the sofa, her bulk formidably arrayed in purple satin, and upon her crimped locks a turban embellished with roses and feathers.

No one could have doubted Mrs. Scorton’s good-nature; and very few would have denied her vulgarity. She shook Kitty warmly by the hand, embarrassed her by thanking her for her condescension in coming to Ham Crescent, and said, with a jolly laugh: “Olivia would have it I should not invite you, but ‘Nonsense, my dear,’ I said, ‘I warrant Miss Charing is not so high in the instep she won’t enjoy a frolic as well as anyone!’ I daresay Almack’s may be very well, though I don’t know, for I was never there in my life, but what I say is it sounds mighty stiff and dull to me, and I was always one for a little fun out of the ordinary, as I’ll be bound you are too! Now I must introduce everyone to you, and we can be comfortable. Not that I need to introduce my girls, and I hope I’m not such a simpleton as to present your own cousin to you! But this is Mr. Malham, my dear, that’s promised to Sukey here, as you may have heard. A fine thing to have Sukey going off before her sister, ain’t it? Not that I want to lose my Lizzie, as well she knows, but we all roast her about it—just funning, of course! And this is Mr. Bottlesford. We call him Bottles.”

Kitty knew that she was not going to enjoy the party. As she curtsied slightly to both gentlemen, Mrs. Scorton outlined for her benefit the plan for the evening. After dinner, she said, they would play at lottery—tickets, or some other jolly, noisy game, for an hour, and then drive to the Opera House. “And Tom shall escort you home in good time, I promise you, for I don’t mean to let any of you girls stay much after midnight, and so I warn you, for although I’m as fond as you are of a masquerade it don’t do to be lingering on when things get a trifle too free, as very likely they will.”

After this she begged Kitty to take a chair near the fire, and Miss Scorton, who had been much impressed by as much of Lady Buckhaven’s house as she had been privileged to see upon her one and only visit to it, began to ply her astonished guest with questions which were as artless as they were impertinent. She wanted to know how many saloons there were in the house, how many beds her ladyship could make up, how many covers could be laid in her dining-room, how many footmen she employed, and whether she gave grand parties every night, and had a French maid to wait upon her. There seemed to be no end to her interrogation, but after about twenty minutes she was interrupted by the dinner— bell, and the company trooped downstairs to the dining— room.

Here they were joined by the master of the house, of whose existence Kitty had previously been unaware. He was quite as stout as his wife, but by no means as good-natured. When he shook hands with Kitty, he grunted something which she might, if she chose, understand to be a welcome; and his wife explained, as though it were a very good joke, that he disliked parties, and never joined them except to eat his dinner. With these encouraging words, she directed Kitty to the chair at his right hand, disposed her own ample form at the foot of the table, beckoned the Chevalier to sit beside her, and said that she hoped all her guests had brought good appetites with them.

They were certainly needed. Mrs. Scorton was a lavish housewife, and prided herself upon the table she kept. When the soup was removed, the manservant, assisted by a page and two female servants, set a boiled leg of lamb with spinach before his master, a roast sirloin of beef before his mistress, and filled up all the remaining space on the board with dishes of baked fish, white collops, fricassee of chicken, two different vegetables, and several sauce-boats. Everyone but Mr. Scorton, who applied his energies to the tasks of carving and of eating, talked a great deal; and Tom Scorton, who was seated beside Kitty, entertained her with a long and boring story of a horse he had bought, and subsequently sold at a very good price, and without a warranty, upon the discovery that the animal was for ever throwing out a splint.

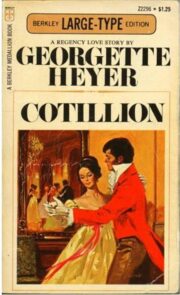

"Cotillion" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Cotillion". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Cotillion" друзьям в соцсетях.