These reflections were disturbed by Lord Dolphinton, who raised his head again, and gave utterance to the thought which had been slowly germinating in his brain. “I’d as lief not be an Earl,” he said heavily. “Or a Viscount. Freddy’s going to be a Viscount. I wouldn’t wish to be. I wouldn’t wish to be a Baron, though that’s not much. George—”

“Yes, yes, we all know I am a Baron! You need not enumerate the degrees of nobility!” said Biddenden, in an exasperated tone. “You had as lief not be a peer of any degree! I am sure I don’t know what maggot has got into your head now, but that at least I have understood!”

“There is no occasion for you to speak so roughly,” said Hugh. “What would you like to be, Foster?”

Lord Dolphinton sighed. “That’s just it,” he said mournfully. “I wouldn’t like to be a military man. Or a parson. Or a doctor. Or—”

The Rector, realizing that the list of the occupations his cousin did not desire to engage in was likely to be a long one, intervened, saying in his grave way: “Why don’t you wish to be an Earl, Foster?”

“I just don’t,” said Dolphinton simply.

Fortunately, since his elder cousin showed signs of becoming apoplectic, any further remarks which he might have felt impelled to make were checked by the arrival on the scene of his great-uncle and host.

Mr. Penicuik, who had retired to his bedchamber after dinner for the purpose of having all the bandages which were bound round a gouty foot removed and replaced, made an impressive entrance. His butler preceded him, bearing upon a silver salver a box of pills, and a glass half-filled with an evil-looking mixture; Mr. Penicuik himself hobbled in supported on one side by a stalwart footman, and upon the other by his valet; and a maid-servant brought up the rear, carrying a heavy walking-stick, several cushions, and a shawl. Both Lord Biddenden and his brother started helpfully towards their infirm relative, and were cursed for their pains. The butler informed Lord Dolphinton in a reproachful whisper that he was occupying the Master’s chair. Much alarmed, Dolphinton removed himself to an uncomfortable seat at some distance from the fire. Mr. Penicuik, uttering sundry groans, adjurations, and objurgations, was lowered into his favourite chair, his gouty foot was laid tenderly upon a cushion, placed on the stool before him, another cushion was set at his back, and his nephew Hugh disposed the shawl about his shoulders, rather unwisely enquiring, as he did so, if he was comfortable.

“No, I’m not comfortable, and if you had my stomach, and my gout, you wouldn’t ask me a damned silly question like that!” retorted Mr. Penicuik. “Stobhill, where’s my cordial? Where are my pills? They don’t do me any good, but I’ve paid for them, and I won’t have waste! Where’s my stick? Put it where I can reach it, girl, and don’t stand there with your mouth at half-cock! Pack of fools! Don’t keep on hovering round me, Spiddle! I can’t abide hoverers! And don’t go out of hearing of the bell, for very likely I shall go to bed early, and I don’t want to be kept waiting while you’re searched for all over. Go away, all of you! No, wait! Where’s my snuff-box?”

“I fancy, sir, that you placed it in your pocket upon rising from the dinner-table,” said Stobhill apologetically.

“More fool you to have let me sit down before I took it out again!” said Mr. Penicuik, making heroic efforts to get a hand to his pocket, and uttering another anguished groan. An offer of Lord Biddenden’s Special Sort, put up in an elegant enamel box, was ungratefully rejected. Mr. Penicuik said that he had used Nut Brown for years, and wanted nobody’s new-fangled mixture. He succeeded, with assistance from two of his henchmen, in extricating his box from his pocket, said that the room was as cold as a tomb, and roundly denounced the footman for not having built up a better fire. The footman, who was new to his service, foolishly reminded Mr. Penicuik that he had himself given orders to make only a small fire in the Saloon. “ Man’s an idiot!” said Mr. Penicuik. “Small fire be damned! Not when I’m going to sit here myself, clodpole!” He waved the servants away, and nodded to his young relatives. “In general, I don’t sit here,” he informed them. “Never sit anywhere but in the library, but I didn’t want the pack of you crowding in there.” He then glanced round the room, observed that it needed refurbishing but that he was not going to squander his money on a room he might not enter again for a twelvemonth, and swallowed two pills and the cordial. After this, he took a generous pinch of snuff, which seemed to refresh him, and said: “Well, I told you all to come here for a purpose, and if some of you don’t choose to do what’s to their interest I wash my hands of them. I’ve given ’em a day’s grace, and there’s an end to it! I won’t keep you all here, eating me out of house and home, to suit the convenience of a couple of damned jackanapes. Mind, I don’t mean they shan’t have their chance! They don’t deserve it, but I said Kitty should have her pick, and I’m a man of my word.”

“I apprehend, sir,” said Biddenden, “that we have some inkling of your intentions. You will recall that one amongst us is absent through no fault of his own.”

“If you’re talking about your brother Claud, I’m glad he isn’t here,” replied Mr. Penicuik. “I’ve nothing against the boy, but I can’t abide military men. He can make Kitty an offer if he chooses, but I can tell you now she’ll have nothing to say to him. Why should she? Hasn’t clapped eyes on him for years! Now, you may all of you keep quiet, and listen to what I have to say. I’ve been thinking about it for a long time, and I’ve decided what’s the right thing for me to do, so now I’ll put it to you in plain terms. Dolphinton, do you understand me?”

Lord Dolphinton, who was sitting with his hands loosely clasped between his knees, and an expression on his face of the utmost dejection, started, and nodded.

“I don’t suppose he does,” Mr. Penicuik told Hugh, in a lowered voice. “His mother may say what she pleases, but I’ve always thought he was touched in his upper works! However, he’s as much my great-nevvy as any of you, and I settled it with myself that I’d make no distinctions between you.” He paused, and looked at the assembled company with all the satisfaction of one about to address an audience without fear of argument or interruption. “It’s about my Will,” he said. “I’m an old man now, and I daresay I shan’t live for very much longer. Not that I care for that, for I’ve had my day, and I don’t doubt you’ll all be glad to see me into my coffin.” Here he paused again, and with the shaking hand of advanced senility helped himself to another pinch of snuff. This performance, however, awoke little response in his great-nephews. Both Dolphinton and the Reverend Hugh certainly had their eyes fixed upon him, but Dolphinton’s gaze could not be described as anything but lack-lustre, and Hugh’s was frankly sceptical. Biddenden was engaged in polishing his eyeglass. Mr. Penicuik was not, in fact, so laden with years as his wizened appearance and his conversation might have led the uninitiated to suppose. He was, indeed, the last representative of his generation, as he was fond of informing his visitors; but as four sisters had preceded him into the world and out of it this was not such an impressive circumstance as he would have wished it to appear. “I’m the last of my name,” he said, sadly shaking his head. “Outlived my generation! Never married; never had a brother!”

These tragic accents had their effect upon Lord Dolphinton. He turned his apprehensive eyes towards Hugh. Hugh smiled at him, in a reassuring way, and said in a colourless voice: “Precisely so, sir!”

Mr. Penicuik, finding his audience to be unresponsive, abandoned his pathetic manner, and said with his customary tartness: “Not that I shed many tears when my sisters died, for I didn’t! I will say this for your grandmother, you two!—She didn’t trouble me much! But Dolphinton’s grandmother—she was my sister Cornelia, and the stupidest female—well, never mind that! Rosie was the best of ’em. Damme, I liked Rosie, and I like Jack! Spit and image of her! I don’t know why the rascal ain’t here tonight!” This recollection brought the querulous note back into his voice. He sat in silence for a moment or two, brooding over his favourite great-nephew’s defection. Biddenden directed a look of long-suffering at his brother, but Hugh sat with his eyes on Mr. Penicuik’s face, courteously waiting for him to resume his discourse. “Well, it don’t signify!” Mr. Penicuik said snappishly. “What I’m going to say is this: there’s no reason why I shouldn’t leave my money where I choose! You’ve none of you got a ha’porth of claim to it, so don’t think it! At the same time, I was never one to forget my own kith and kin. No one can say I haven’t done my duty by the family. Why, when I think of the times I’ve let you all come down here—nasty, destructive boys you were, too!—besides giving Dolphinton’s mother, who’s no niece of mine, a lot of advice she’d have done well to have listened to, when my nevvy Dolphinton died—well, there it is! I’ve got a feeling for my own blood there’s no explaining. George has it too: it’s the only thing I like about you, George. So it seemed to me that my money ought to go to one of you. At the same time, there’s Kitty, and I’m not going to deny that I’d like her to have it, and if I hadn’t a sense of what’s due to the family I’d leave it to her, and make no more ado about it!” He glanced from Biddenden to Hugh, and gave a sudden cackle of mirth. “I daresay you’ve often asked yourselves if she wasn’t my daughter, hey? Well, she ain’t! No relation of mine at all. She was poor Tom Charing’s child, all right and tight, whatever you may have suspected. She’s the last of the Charings, more’s the pity. Tom and I were lads together, but his father left him pretty well in the basket, and mine left me plump enough in the pocket. Tom died before Kitty was out of leading-strings, and there weren’t any Charings left, beyond a couple of sour old cousins, so I adopted the girl. Nothing havey-cavey about the business at all, and no reason why she shouldn’t marry into any family she chooses. So I’ve settled it that one of you shall have her, and my fortune into the bargain.”

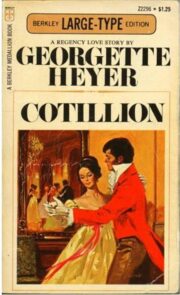

"Cotillion" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Cotillion". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Cotillion" друзьям в соцсетях.