“Just forget about it. Everything will be fine. Harry will get over it. He's just being stupid and overreacting.” They all were. “He should relax his principles for one night, enjoy it and eat his dinner, and not give you such a hard time.”

Olympia felt better as soon as they hung up. But, in spite of her mother-in-law's comforting assurances, she still looked tired and stressed. It was nearly five o'clock, and she wanted to get home to Max. One of her partners walked into her office five minutes later, and saw the look on Olympia's face.

“You look like you've had a fun day,” Margaret Washington said with a tired smile. She'd had a tough day herself, working on an appeal of a class action suit they had brought against a string of factories that were dumping toxic waste, and lost. She was one of the firm's best lawyers. She went to Harvard as an undergraduate, and then on to Yale Law School. She happened to be African American and Olympia wasn't anxious to explain her problems to her, but after circling the subject cautiously for five minutes, she finally spelled it out to her. Margaret had exactly the same reaction Olympia's mother-in-law had had. “Oh for chrissake, we poison the environment, we sell cigarettes and alcohol, half the nation's youth is hooked on drugs they can buy on street corners, not to mention guns, we have one of the highest suicide rates in the world among youth under the age of twenty-five, we get into wars that are none of our goddamn business at every opportunity, Social Security is bankrupt or damn near it, the nation is crippled by debt. Our politicians are crooked for the most part, our educational system is falling apart, and you're supposed to feel guilty about your kids playing Cinderella for one night at some fancy Waspy ball? Give me a break. I've got news for you, there are no whites at my mother's bingo club in Harlem either, and she doesn't feel guilty for a goddamn minute. Harry knows better— why don't you tell him to go picket someone? This isn't a Nazi youth movement, it's a bunch of silly girls in pretty white dresses. Hell, if I were in your shoes, and I had a kid, I'd want her to do it, too. And I wouldn't feel guilty about it, either. Tell everyone to relax. It doesn't bother me, and I boycotted just about everything on the planet all through college and law school. This one wouldn't even have raised my eyebrows.”

“That's what my mother-in-law said. Harry said it was a disrespect to every member of his family who died in the Holocaust. He made me feel like Eva Braun.”

“Your mother-in-law sounds a lot more sensible. What else did she say?” Margaret asked with interest. She was a spectacular-looking woman, a few years younger than Olympia, and she had modeled in college. She had been in Harper's Bazaar and Vogue in order to supplement her scholarship at Harvard.

“She wanted to know what I thought of black velvet, and how soon we could shop for her dress.”

“Precisely. My sentiments exactly. Fuck all of them, Ollie. Tell your revolutionary kid to shape up, and your husband to give it up. This isn't on the ACLU's radar screen, it doesn't need to be on his either. And your ex-husband sounds like a real jerk.”

“He is. If he gets a chance, he'll stir the pot. He'd rather have a kid on life support than one not making her debut. I just want them to have fun, and do the same thing I did. In my day, it wasn't a big deal, it was just something you did. I did it in the seventies, in the sixties everyone refused to, in the forties and fifties you had to, to find a husband. It isn't about that anymore, it's about wearing a dress and going to a party. That's all it is. A one-night stand for tradition and the family album. Not a travesty of social values.”

“Believe me, I never lost a night's sleep over it when I was a kid, and I knew girls at Harvard who did it in New York and Boston. In fact, one of them invited me to go, but I was modeling in Chicago that weekend to pay for school.”

“I hope you come,” Olympia said generously, and Margaret grinned.

“I'd love to.” It never even remotely occurred to Olympia that Margaret being there would cause a stir, nor did she care. So far, she had invited a Jewish woman as her guest, and an African American, and she was Jewish now herself. And if the committee didn't like it for some reason, though she doubted it, she didn't give a damn.

“I just hope Harry comes, too,” she said, looking sad. She hated fighting with him.

“If he doesn't, it's his loss, and he'll look stupid. Give him time to come down off his high horse. It should tell him something that his mother approves and thinks the girls should do it.”

“Yeah,” Olympia said with a sigh. “Now all I have to do is convince the girls. Or Veronica at least. If not, she and Harry can picket the event. Maybe they can carry signs objecting to the women wearing fur.”

They both laughed, and half an hour later Olympia went home. The atmosphere at home was strained that night. None of them said a word at dinner, but at least this time everyone sat down and ate. By the time they went to bed that night, Harry had unbent a little. She didn't discuss the deb ball with him, nor with Veronica. She didn't touch the subject with either of them, until Veronica went berserk three days later when she got a letter from her father.

He had written her the threat not to pay her or Ginny's college tuition if both girls didn't come out, and she ranted and raved at how disgusting he was, how manipulative, and how horrible to hold her hostage and blackmail her. Olympia didn't comment on his threat, but she noticed that the girls made peace with each other after that. Veronica didn't say that she would come out, but she no longer said she wouldn't, either. She didn't want her actions to hurt her sister, or to force her mother to pay for their entire tuition. She was furious with her father now, and commented liberally on what shit values he had, what a bastard he was, and how stupid the whole thing was.

Olympia sent her check in to The Arches for both of them, and assured them that both girls were thrilled to attend the ball. She said nothing more about it to Harry, and figured they had plenty of time to work it out before December. His only comment to her was late one night after Charlie came home from Dartmouth for the weekend and mentioned it. Harry said only three words to both of them, which said it all.

“I'm not going,” he growled, and then left the room, leaving Olympia to discuss it with her elder son.

“That's fine,” Olympia said quietly, remembering what his mother had said, and Margaret Washington. She had seven months to change his mind.

Charlie agreed to be Ginny's escort for the ball, although she had recently met a boy she liked. She had taken her mother's advice about not inviting a romantic interest to be her escort for the ball. A lot could change in seven months. Olympia was counting on it. She still needed to turn Harry and Veronica around. For the moment at least, everyone seemed to have calmed down.

Chapter 3

When Charlie came home from Dartmouth for the summer, he seemed quiet to his mother. He had done well in school, was playing varsity tennis, had played ice hockey all winter, and was starting to take up golf. He saw all his friends, hung out with his sisters, and went on a date with one of Veronica's friends. He took Max out to throw a ball in Central Park, and took him to a beach on Long Island in June. But no matter how busy he was, Olympia was worried about him. He seemed quieter than usual to her, distant, and out of sorts. He was leaving soon for his job at the camp in Colorado, and claimed he was looking forward to it. Olympia couldn't put her finger on it, but he seemed sad to her, and uncomfortable in his own skin.

She mentioned it to Harry after they played tennis one Saturday morning, while Charlie babysat for Max. She and Harry loved playing tennis and squash with each other. It gave them time alone and relaxed them both. They cherished the time they managed to spend alone, which was infrequent, as they spent most of their evenings and weekend time with Max. With Charlie home, they had a built-in babysitter. He was always quick to volunteer to take care of Max for them.

“I haven't noticed anything,” Harry said, wiping his face with a towel, after the game. He had beaten her, but barely. They had both played a good game, and were in great shape. She had just shared her concerns about Charlie with him, and he was surprised to hear that Olympia thought Charlie was out of sorts. “He seems fine to me.”

“He doesn't to me. He hasn't said anything, but whenever he doesn't know I'm watching him, he looks depressed, or pensive, or just sad somehow. Or worried. I don't know what it is. Maybe he's unhappy at school.”

“You worry too much, Ollie,” he said, smiling at her, and then he leaned over and kissed her. “That was a good game. I had fun.”

“Yeah.” She grinned at him as he put an arm around her. “Because you won. You always say it was a good game when you win.”

“You beat me the last time we played squash.”

“Only because you pulled a hamstring. Without that, you always beat me. You play squash better than I do.” But she often beat him at tennis. It didn't really matter to her who won, she just liked being with him, even after all these years.

“You're a better lawyer than I was,” Harry said, and she looked startled. He had never said that to her before.

“No, I'm not. Don't be silly. You were a fantastic lawyer. What do you mean? You're just trying to make me feel better because you beat me at tennis.”

“No, I'm not. You are a better lawyer than I am, Ollie. I knew it even when you were a law student. You have a solid, powerful, meticulous way of doing what you do, and at the same time you manage to be creative about it. Some of what you do is absolutely brilliant. I admire your work a lot. I was always very methodical about my cases when I was practicing. But I never had the kind of creativity you do. Some of it is truly inspired.”

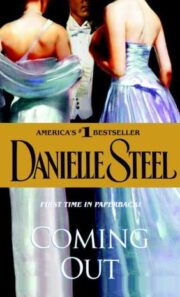

"Coming Out" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Coming Out". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Coming Out" друзьям в соцсетях.