I was angry with myself. Why had I not returned sooner? Why had I not guessed what they would do? With no one to turn to, she had been ground down, until at last, in a moment of weakness, she had given her consent to the union, and had then been married by special licence before she could take it back.

I thanked Mrs Upland for her kind words and left her to lay her flowers on her husband’s grave, for though he had died ten years earlier, she still placed fresh flowers there every day.

Without any idea of what I was going to do, I started walking towards the house. I grew more and more angry as I went on. I entered through the French windows and went straight into my father’s study. He was there, sitting at his desk, his quill in his hand as he examined a pile of papers.

He looked up when I entered the room, and then continued with his work.

‘So, you are home.’

‘Yes, sir, I am home, and I demand an answer from you. What did you mean by it, blighting the happiness of a young woman, your own ward, for ever? When I think of the inducements, nay the cruelties, you used to get her to consent to the match — ’

‘How very dramatic you are,’ he said drily, without favouring me with so much as a look. ‘You speak as though I locked her in a dungeon and fed her on bread and water.’

‘You locked her in her room — ’

‘Which is a comfortable apartment, decorated to her own taste, complete with a sitting room, filled with needlework, paints and other amusements to help her to pass the time.’

‘You deprived her of society — ’

‘She had her companion.’

‘ — and frightened her into the match.’

‘Not a bit of it. She saw the folly of clinging to you when she knew I would never consent to the match, and she grew to like your brother. He presented himself to her in a sober condition and sat with her on many occasions in her sitting room, taking her gifts, and telling her of the happy future that awaited her as his wife.’

‘She would never have married him if she had not been ground down. You cannot deny it, for if she had changed her mind freely, then there would have been no need for a hurried wedding, nor any need to forbid me the house until she was married.’

‘Whatever the case, she is married now, and in London, which means that there is no purpose to your rantings. Accept it. It is done.’

‘Never.’

‘Now that she has gone, you may stay here for as long as you wish,’ he said, as though I had not spoken.

‘Remain here, where every corner reminds me of her?’ I asked in disbelief. ‘Where I have to see you every day, and be reminded of the heinous thing you have done?’

‘Then return to Oxford, and go on with your studies,’ he said, whilst giving nine tenths of his attention to his papers, and only one tenth to me. ‘Let me know when you achieve your ambitions. Perhaps I will employ you as my clerk.’

To say more was useless. I left the study, passing my hand over my eyes as I reached the hall, and then, turning my back on Delaford, I walked to the stage post and at last boarded the stage for Oxford.

As it travelled away from the neighbourhood, I felt myself travelling away from all my happiness in life, into a future that was cold and dark.

Wednesday 29 July

My thoughts were in turmoil this morning, for I knew I could not resume my studies without the backing of my father, and I was determined never to touch his money, or anything of his. Besides, the idea of becoming a lawyer was suddenly abhorrent to me, for its purpose had been to support Eliza and without that purpose there was no point to it.

I was in the midst of this turmoil when the stagecoach stopped at the Black Swan. Feeling tired, for I had not eaten since yesterday, I left the stage and went inside. I ordered a plate of mutton and sat in a corner, not wanting company, but as luck would have it, company found me anyway, and company of a sort to do me good.

‘Brandon? Brandon, is that you? It is!’

I looked up to see Geoffrey Parker and his uncle.

‘You look as though you need some company,’ he said.

My mood began to lift at the sight of his friendly face, for we had been friends at Oxford, and when he asked me how my family was, and how Eliza was, saying, ‘Is she as pretty as ever? No, don’t tell me, she is prettier!’ I broke down and told him everything.

‘And now I must find something to do with myself, or go mad,’ I finished.

‘You should join the army,’ said his uncle.

It turned out he had some influence and he promised to help me if I had a mind to enlist.

‘I have a little money from my mother,’ I said. ‘How much would it cost me to buy a commission?’

He gave me all the particulars and I saw that it could be done.

‘You will have activity, employment and company,’ he said, ‘all good things for a man in your condition.’

I began to see a future for myself; not the future I had wanted, but one in which I could at least be respectable and respected.

It was little enough, but it was better than the alternative, to spend my days sunk in despair, lost in the past, a past to which I could never return.

And so I thanked him, and asked him to use his influence, and now, who knows what the future holds?

Tuesday 6 October

‘It was a bad business, a very bad business,’ said Leyton, shaking his head, as we met again for the first time in months, in Oxford, an Oxford changed for me for ever, for it was no longer the scene of youthful hopes, but the scene of a fool’s paradise.

I told him what had happened to me.

‘I wondered why you had changed your mind about the lodgings,’ he said, ‘but when your letter arrived two months ago, I was too busy to wonder very much, and I am only sorry the reason was such a sad one. I can understand why you did not feel you could continue at Oxford, but whatever induced you to buy a commission?’

I could not help thinking that if things had been otherwise, our conversation would not have been about my plan of going into the army, it would have been about the lodgings he had found for Eliza and me, and our future in Oxford.

‘I had to do something,’ I said. ‘I thought the bustle of a new career would distract my thoughts, but I still think about her constantly. I cannot stay in England, and I plan to purchase an exchange.’

‘Where will you go?’

‘The Indies. Once I am far away, I must hope to forget her, as I must hope she forgets me.’

He looked at me doubtfully.

‘I must hope she forgets me,’ I said. ‘How else can there be any happiness for her? If she remembers what we were to each other and compares it with what she has now ... But if Harry treats her well, if she has friends and fine clothes and parties, with plenty of distractions, I am persuaded she can be happy in her new life.’

He looked at me pityingly, for he knew I believed it as little as he did.

But Eliza was married. She was beyond my reach. If I went to her, I would dishonour her, and so I must go far away.

‘Give it some time before you purchase your exchange,’ he said. ‘You will grow more accustomed to the situation with time, and you will find a hundred miles as efficacious a distance as a thousand.’

‘I do not trust myself with only a hundred miles between us. I must have half the globe, or else what is to prevent me from going to her and ruining her? For to live without her is agony. I must have occupation, and change, and distance from Eliza.’

He looked at me sympathetically then turned the subject, trying to take my mind from my troubles by his lively conversation. I was grateful to him, but it did no good. I could not tear my thoughts from Eliza.

1779

Wednesday 24 March

And so I find myself on a ship bound for the Indies, and at last I have found my sea legs and I can manage to keep my food inside me. The vessel is an East Indiaman, and as fine a ship as ever sailed the seas, or so her captain tells me. He is a talkative fellow, prosperous and well-made, and instils confidence into those around him.

‘This is my fourth run,’ he told me as we stood together on the deck. ‘Yes, I’ve done very well out of the East India Company. I’ve had three good runs and amassed a fortune. How much do you think I have made?’

I guessed at five thousand pounds, and he laughed. Then I guessed at ten thousand, and he laughed again.

‘Double it and then some,’ he said. ‘Almost thirty thousand pounds! What with free transport for freight giving a man a chance to make something out of his own bit of cargo, and the salary, it’s a good life, being a captain. A man would have to be a fool to make less than four thousand a trip, and I’m no fool! On my last trip I made twelve! But this will be my last voyage. I could make more money by staying, there’s always work for experienced captains, but I’m tired of making it. I want to spend it. When my ship retires, so do I. It’s a hard passage, and it takes its toll on men and ships alike.’

He told me of his plans to buy a small estate and find a wife, and I wished him well, but being in no mood to hear him talk about the woman he would like to marry, I soon left him and joined my comrades; a varied group, but I liked Green and Wareham, and I thought I would soon be able to call them friends.

The talk was all of Warren Hastings. Being eager to learn as much as I could about the strange new world that was opening up around me, I listened avidly as they spoke of bribery and corruption, and of Hastings’s governorship, and of the difficulties that lay ahead of me. As I imagined the exotic locations awaiting me, England seemed a long way away.

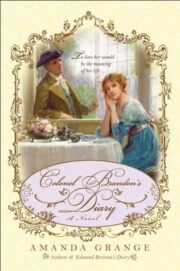

"Colonel Brandon’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.