‘You forget, it will not be yours for some years yet. Even if I agree to use it, we will have to manage on our own for some time. We will have to live simply, and we will not have money for the elegancies of life, but we will be together.’

‘As long as your father gives in. Go and speak to him now, James, do not delay. See if you can persuade him. Let us know our fate.’

‘There is no point in speaking to him before he has had his breakfast, for he will not listen to me favourably on an empty stomach. But once he has eaten, I hope to find him in a mellower frame of mind, and then, perhaps, he will see that we are determined not to be parted.’

We continued on our way, making plans for the future, until at last I felt it was late enough to speak to my father. I went indoors and found him in his study. He looked up when I entered but then looked down again and carried on with his letter.

‘I hope you have not come to speak to me again about your brother’s engagement.’

‘No. I have come to speak to you about Eliza’s engagement. ’

‘They are one and the same.’

‘You cannot mean to force her into a marriage that is distasteful to her,’ I said. ‘She deserves more from you than that.’

‘She will soon accustom herself to it, as will you, no matter how much you both think otherwise at the moment. Young people always think it is the end of the world if they cannot choose their own spouse, but they quickly realize that the elegancies and comforts of life are worth more than so-called love, for elegancies and comforts are solid and longer lasting. If the young couple are fortunate, and have sensible elders to protect them, they realize this fact before they rush into a precipitate marriage. If they are unlucky, they realize it afterwards, when they are left with nothing but penury and bitterness to comfort them for their folly.’

I remonstrated with him, but he would not listen, and at last I had to retreat, defeated.

Eliza saw by my face that my news was not good, and when I had told her what he said, she replied, ‘Then we have to elope.’

I did not like it, but I could not see any way of avoiding it.

‘You are right, my love, there is no alternative.’

‘We can leave tonight.’

‘Yes, tonight. Have your maid pack your things whilst we are at dinner. We will leave at midnight, when my father and Harry have retired. I will have a carriage meet us at the end of the lane, so that the horses do not disturb the household, and then we will be away.’

She took my hands and I felt them tremble.

‘Frightened?’ I asked her.

‘No. Excited at the thought of our new life together. Where will we go once we are married, do you think?’

‘We will go to Oxford. We can take lodgings and set up house there. You will like Oxford, it is an interesting place, and there are some remarkable people. Besides, I have a friend whose father is a lawyer there and I think he might find a place for me.’

She took my arm and squeezed it as we walked towards the stables.

‘I am looking forward to it already!’ she said. ‘This has been a good thing, after all, James, for it has brought all the waiting to an end. Now we can be together, as we were meant to be.’

We continued to talk of our future until we reached the stables, then she left me and I went into town to make the necessary arrangements.

Once my business was done, I returned home and told my valet to pack my things as I was going away. I wrote a letter to my father and put it in my pocket, ready to place on his desk just before midnight.

I dressed for dinner and was about to go downstairs when the door opened, and to my surprise, my father entered the room. His presence there was so unusual that my heart misgave me, and as soon as he began to speak, I knew that we were undone.

‘I have some advice for you, James,’ he said, in his dry manner. ‘Always believe the worst of people, my boy, and then they will never disappoint you. I have thought the best of people, and I have been sadly deceived, for I have discovered that my ward has been planning to elope to Scotland behind my back, and that my son has been her partner in this treachery; and this, when he has plans to become a lawyer.’

‘I can assure you, sir — ’

‘You can assure me of nothing, my boy, so pray do not add falsehood to your many faults. Eliza’s maid is loyal to me, or, at least, loyal to the reward she hopes I will give her, and she has told me everything I need to know. You will go to your great-aunt Isabella, and you will not be welcome in this house until your brother is safely married to Eliza.’

I drew myself up.

‘Then, sir, I shall never be welcome here again, for Eliza will never marry my brother.’

‘Dear me, how vainglorious young people are! I hesitate to shatter your illusions, but Eliza’s future has nothing to do with you. She will see reason and she will do her duty, like every other young girl before her.’

‘She does not love him, and you cannot force her to marry him,’ I said coldly. ‘Would it not be better to accept that she is in love with me and allow our marriage?’

‘We have already spoken of this at length and we will speak of it no more. You will leave for your aunt’s house at once. The carriage is at the door.’

‘I am sorry to disappoint you, sir, but I will not go without Eliza.’

He grew irascible.

‘That sounds very definite, but I assure you, you are mistaken, for if you refuse to leave, then the footmen will escort you to the coach.’

I looked beyond him and saw that two of the footmen were standing in the passage behind him. I could tell that they did not like it, for their faces were grim, but I knew that they would do their duty or lose their positions, so to spare them, and myself, the indignity of a forcible ejection, I said, ‘You have me at a disadvantage, I see. Very well. I will do as you say.’

I knew there was no more I could do for the moment, so I picked up my portmanteau and he stood aside to allow me to leave the room. I went along the corridor, followed by my father and the footmen, but as I did so, I was already planning to return for Eliza. I would do it when my father was away from home, making his annual visit to London to attend to business matters. I was only sorry that I would not have a chance to speak to her before I left and tell her of my new plan.

As I reached the top of the stairs, however, I heard the sound of footsteps and I saw Eliza running towards me from her chamber in the east wing. Harry, unusually alert, was following her, and he caught up with her at the top of the stairs, putting his arms round her to restrain her. He grinned at me as he did it, and I lunged towards him, ready to knock him down. But the two footmen closed in behind me and held my arms.

‘I will never marry him!’ cried Eliza, struggling to free herself. ‘Never. They cannot make me. Nothing will ever make me abandon you. I love you, James. Only you.’

‘We will be together, I promise you,’ I said.

She became calm and my brother let her go. My last sight of her was of her standing upright, with a defiant gleam in her eye, at the top of the stairs.

I went out to the carriage.

Instead of setting out for Gretna Green, as I had hoped, I found myself setting out for my great-aunt’s house. But I knew that all was not lost. It was a delay, and not a disaster.

Tuesday 30 June

The journey was long and uncomfortable, for my father had ordered the old coach, and it rumbled along at a funereal pace, stopping only to change the horses on its way to Langley Castle. I fell asleep at last, rocked by the motion, and arrived with aches and pains in my neck and legs but otherwise refreshed.

The house was as grim as I remembered it. Grey turrets were outlined against the gloomy sky, and I felt my spirits drop as I went inside.

There was an air of decay in the hall, with its suits of armour and weapons from bygone eras displayed as though they were treasures. They had not been cleaned for a very long time. The metal was dull. The portraits of dour ancestors frowned down on me, as if condemning me for being young and in love.

Horsby, looking even more ancient than the last time I saw him ten years ago, walked unsteadily in front of me with a disapproving air and showed me into the drawing room.

It was as cheerless as the hall, with its heavy, old-fashioned furniture and its tapestries on the walls. But there was one unexpected gleam of colour, for a young woman was sitting on a faded sofa, and as she rose in a rustle of silk, I saw that she was my sister.

‘Catherine, what are you doing here?’ I asked her.

She looked at me as though I were a disobedient seven-year-old.

‘George and I are visiting Aunt Isabella. I do not need to ask what you are doing here. A letter arrived from my father several hours ago, delivered by messenger; and if you needed any proof of how angry he is, you have it in the fact that he went to the expense of using a messenger instead or relying on the post. Really, James, I cannot think how you came to be so foolish! Attempting to elope with Eliza. What nonsense!’

‘I happen to love her,’ I said, with dignity.

‘That would be ridiculous enough coming from a school-girl, but coming from a man it is unforgivable. I am not surprised that our father sent you away. Fortunately, I know just the young woman to make you forget about Eliza. Her name is Miss Heath. She is utterly charming. Her hair and eyes are just like Eliza’s. In fact, she is so like her that you will scarcely notice the difference.’

‘I believe that I can tell the difference between the woman I love and a complete stranger,’ I remarked.

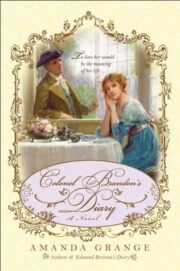

"Colonel Brandon’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.