‘But ... this is a joke!’ said Eliza, but she did not sound sure.

I was not sure, either, and now the glances we exchanged were perturbed.

‘A joke! How you young people express your good humour these days! In my young day, we would have said, This is delightful. But times move on and language, just like fashion, is always changing. Yes, my dear, it is a joke.’

‘You are teasing me, sir,’ she said, looking at me anxiously and then looking back at my father.

‘Is this another of youth’s sayings?’ he asked. ‘I am sadly behind the times, I fear, and I do not always understand them.’

‘Pray, do not jest with me, sir,’ she said. ‘Put me out of my misery and tell me it is not true.’

‘Your misery? My dear Eliza, not a moment ago you were in raptures about it,’ he said incredulously; but, as so often happens with my father, I did not know if his manner was real or feigned.

‘I assure you, sir, I was not,’ said Eliza. ‘I thought you were teasing me.’

‘For what purpose?’ he enquired curiously.

‘I do not know.’

‘Nor do I. I cannot see how claiming you are to marry my son and heir can be construed as teasing, but since you seem to be in some doubt then I will say it plainly. As your guardian, I have found you a suitable husband. The engagement will be announced at the ball and the marriage will take place at the end of the summer.’

‘No!’ said Eliza, rising in her seat and throwing her napkin down on the table.

‘No?’ asked my father in surprise.

‘No, sir, I am sorry, but I cannot marry Harry.’

‘Well, well, that sounds very definite.’

‘I do not love him.’

‘And what, pray, does that have to do with anything?’

‘It has everything to do with it,’ she cried passionately.

‘Marriages are contracted for the good of the parties involved, not for some romantic notions. You are of a marriageable age and it is my duty as your guardian to find you a husband. Your fortune entitles you to an eldest son, one from an old and respectable family with a fine estate, who can provide you with comfort, ease and security, and that is what you will have.’

‘It is not enough for me. I will not marry without love!’ she declared vehemently.

‘Dear me, you have been reading too much poetry. You have confused it with reality. There is no such thing as love.’

‘That is where you are wrong, sir. There is; I have found it. I am in love with James.’

‘James?’ asked my father, surprised. ‘The future attorney? My dear, it is you who surely jest. What kind of life can he give you, a mere boy of eighteen with no influential friends or relations to help him, and no prospects? Unless he marries an heiress he will have next to nothing, and if he marries a young lady with thirty thousand pounds then he can hardly be expected to marry you as well.’

‘I am an heiress,’ she said defiantly.

‘Ah, I see,’ he said, turning to me. He raised his glass. ‘I must congratulate you, James. It seems I have underestimated you. I believed all your nonsense about studying hard and gaining a degree, but I see now that your interest in the law was nothing but a screen. You have not been cultivating useful friendships at university, for you needed none. You have been courting an heiress closer to home.’

‘I do not want Eliza’s fortune,’ I declared, having had enough of his humours and, being so nearly touched, becoming angry. ‘Indeed, I will not touch a penny of it.’

‘I should hope not, for it will belong to your brother, and although he is an idle fellow in many respects, I imagine he would make a fuss if you tried to steal his money.’

‘You cannot marry Eliza to Harry, sir. Look at him!’ I said, for Harry was slumped across the table. ‘Let me marry Eliza. Give me your permission, give us your blessing, and you will not regret it, I promise you.’

‘There can be no question of it. I would be remiss in my duties if I allowed my ward to marry a younger son.’

‘But a younger son who loves her!’

‘Love again! And this time from a young man, who ought to know better, instead of a naïve young girl. It must be education that has done this to you. Indeed, education appears to have ruined both my sons; it is the curse of literature. My eldest son seems to think he is Tom Jones, for he is busy seducing every wench in the countryside, whilst my youngest thinks he is Romeo! Worse still,’ he said, turning to Eliza, ‘he has convinced you that you are Juliet, my dear.’

‘It is nothing of the sort,’ I said. ‘We are not children who do not know the ways of the world. We are quite old enough to understand the realities of life, sir, I do assure you. But we have known for some time that we are in love with each other, and we planned to marry anyway.’

‘Do you not think, if your intentions towards Eliza had been honourable, you should have asked her guardian’s permission to pay your addresses to her?’ he asked.

‘I ...’ I drew myself up. ‘You are right, sir. I should have done so. I ask you now. May I have your permission to address your ward?’

‘Certainly not. You are far too young, and you have nothing to offer her. Furthermore, she is already engaged.’

‘To a man she does not love. You are abusing your position. You are marrying her to Harry for her money.’

‘It is good of you to give me the benefit of your experience and to advise me on my responsibilities as a guardian, but you must allow me to do as I think fit instead of following the guidance of an eighteen-year-old boy.’

‘Harry can have my money,’ said Eliza. ‘I do not want it. I will marry James without it.’

‘My dear, I cannot allow it. It seems sensible to you now, at seventeen, but you would never forgive me at twenty-seven, and rightly so. You will gain stability and security from your marriage, as well as standing in the neighbourhood, and your future will be assured. Harry, in return, will gain the means to pay off the family debts and restore the estate. It is an estimable match in every way.’

‘I cannot stand by and — ’ I began, but he cut me off.

‘What have they been teaching you at Oxford? Sedition and revolt, it would seem, when they should have been teaching you to respect your elders. However, amusing as this conversation might be, I regret I must now put an end to it. Eliza, you will wed Harry, and, James, you will find your own heiress to marry.’

He pushed his chair back from the table.

‘And if I do not want to be Harry’s wife?’ asked Eliza defiantly.

He stood up.

‘We none of us have what we want in this world. If we did, I would have dutiful children who would do as I bid them with a smile; instead of which I have a drunkard for an heir, a fool for a younger son and a disobedient girl for a ward. But we all have our disappointments in life, and I see no reason why you should not have yours as well as anyone else.’

He would discuss it no more in the dining room, and once we retired to the drawing room, he took up his newspaper so that we could not discuss it then, either.

Harry snored in a corner. Eliza played the piano listlessly and soon, declaring she was tired, retired for the night.

‘I will not marry him,’ she said to me in an undertone as she passed me on her way out of the room.

‘Never fear, it will not come to that,’ I said.

And it will not. I will not let her marry my brother.

Saturday 27 June

I slept badly, and when I found Eliza walking in the garden at dawn, I knew that she had slept badly, too.

‘James!’ she said, turning towards me with an anguished face. ‘What are we to do? I cannot believe that twenty-four hours can make so much difference. Yesterday we were so happy — and now ...’

‘Never fear,’ I said, taking her hands consolingly. ‘I will speak to my father again. Now that he has had time to think about it, he must see that it is impossible and he will relent.’

She sighed from the bottom of her heart.

‘That is a vain hope, you know it as well as I do. He has already decided, and nothing you or I can say will change his mind. Even if he relents as far as your brother is concerned, he will never allow me to marry you.’

‘Courage!’ I said, taking her arm and walking on with her. ‘We will be together, no matter what, Eliza. That I promise you.’

‘But how can you promise it? If he refuses to see reason, then we are lost.’

‘No. If all else fails, then we will elope.’

‘Elope?’ She turned to me with hope in her eyes. ‘Oh, yes, James, that is what we must do. We can go to Scotland and be married there.’

‘But first I must speak to my father again,’ I said. ‘I must give him a chance to change his mind. An elopement must be our last resort, for it will ruin your reputation — ’

‘What do I care for my reputation if I can be with you? ’

‘And we will have very little to live on. I have some money from my mother which should enable us to manage — ’

‘Until I come into my inheritance.’

‘Until I find some employment. I have told you before — ’

‘The situation is different now. You must see that! Without the support of your family, we will need more money, and I have money. We must use it, James.’ She set her chin stubbornly. ‘I will not marry you otherwise.’

‘We will talk about this later.’

‘No,’ she said, determined. ‘We will talk about it now.’

‘Very well,’ I conceded. ‘We will use your fortune if we need it.’

‘And that is as much as I can hope for, I suppose, though it seems nonsensical to do without it when our lives would be so much more comfortable with it.’

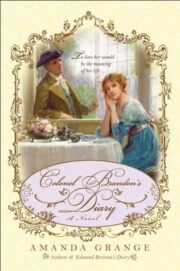

"Colonel Brandon’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.