Marianne joined us for breakfast this morning, but it soon became obvious that she could not sit up, and she retired, voluntarily, to bed.

‘Poor girl, she is very bad,’ said Mrs Jennings, with a shake of her head. ‘Miss Dashwood, I advise you to send for Charlotte’s apothecary. He will be able to give her something to make her feel better.’

‘Yes, indeed, Mama, we must send for him at once,’ said Charlotte.

‘You are very kind,’ said Miss Dashwood, and her ready compliance showed me that she, too, thought the case to be serious.

The apothecary came, examined his patient, and though encouraging Miss Dashwood to expect that a very few days would restore her sister to health, yet by pronouncing her disorder to have a putrid tendency, and by speaking of an infection, gave instant alarm to Charlotte on the baby’s account.

Mrs Jennings looked grave, and advised Charlotte to remove at once with the baby.

Palmer at first ridiculed their fears, but their anxiety was at last too great for him to withstand and within an hour of the apothecary’s arrival, Charlotte set off, with her little boy and his nurse, for the house of a near relation of Palmer’s, who lived a few miles from Bath.

She urged Mrs Jennings to accompany her, but Mrs Jennings, with a true motherly heart, declared that she could not leave Cleveland whilst Marianne was ill, for, as Marianne’s mother was not with her, she must take her place.

I blessed her for her kindness, and I regretted that I could do nothing except be there, in case the ladies should have need of me.

I took out my frustrations on the billiard table, and did not retire until the early hours of the morning.

Thursday 13 April

If Marianne had not fallen ill, she would have been on her way home by now, for she and her sister were due to leave Cleveland today, but she is still too ill to think of travelling.

I am beside myself with worry. She should be getting better, but she seems to be getting worse. If only I could go into the sick room! Then I could see how she fared. Her sister tells me that she is tolerable, but I fear the worst. I imagine her pale and drawn, with dark rings under her eyes, and no matter how much I tell myself that I must not indulge in such fancies, I cannot help it.

Not wanting to be a burden to Mrs Jennings, I offered to leave the house, even though my heart cried out against it, but she, good soul, would not hear of it. She said that I must remain, or who would play piquet with her in the evening when Miss Dashwood was with her sister?

Her words came from the goodness of her heart, for she knew of my feelings for Marianne, and I thanked her silently for allowing, nay, encouraging me to remain.

Palmer encouraged me, too, for he had decided to follow his wife, but he did not like to leave the ladies alone, without anyone to assist or advise them should they need it.

And so it was settled that I should stay.

Friday 14 April

The apothecary called again this morning. He was still hopeful of a speedy recovery, but I could see no sign of it. Miss Dashwood and Mrs Jennings were kept busy all day nursing the patient, and when I asked Mrs Jennings how she went on, she told me that Marianne was no better.

I did not retire until late, in case I was needed, but even so, once I reached my bedchamber, I could not sleep. I could only pace the floor and think of Marianne.

Saturday 15 April

‘I knew how it would be,’ said Mrs Jennings, as we sat together this evening. ‘Right from the beginning, I knew how it would be. She was ill, poor girl, but would not acknowledge it, and so she made herself worse before she gave in to nature and took to her bed. It is because she has been lowered by a broken heart. Ay, Colonel, I have seen it before, a young girl fading away after her lover proves false. Willoughby! If I had him here, what would I not say to him, behaving in such a way to my poor young friend. I hope he will be sorry when she dies of it.’

I tried to reason myself out of believing that death would follow, particularly as the apothecary did not seem despondent, but when I had retired and I was alone, I could not help giving in to gloomy thoughts and fearing I would see Marianne no more.

Sunday 16 April

The dawn dispelled my gloom, and I told myself that this was nothing but a common cold; neglected, it is true, but otherwise susceptible to a warm bed and tender care. In a few days, Marianne would be sitting up; in a few days more, she would leave her room; and before the week was out, she would be well again.

The apothecary confirmed my views when he came again this morning, saying that his patient was materially better. Her pulse was much stronger, and every symptom was more favourable than on the previous visit.

Reassured, I went to church for the Easter service.

When I returned, I found that Marianne was still improving.

Miss Dashwood, confirmed in every pleasant hope, was all cheerfulness.

‘I am relieved that I made light of the matter to my mother when I wrote to her to explain our delayed return,’ she said to me, as we sat together whilst Mrs Jennings took her turn in the sick room. ‘I would not have liked to worry her for nothing. As it is, I believe I will be able to write again tomorrow and fix a day for our return.’

But the day did not close as auspiciously as it began. Towards the evening, Marianne became ill again, and when Mrs Jennings relinquished her place to Miss Dashwood, she looked grave.

‘I do not like the look of her. She is growing more heavy, restless, and uncomfortable than before,’ she said, as she entered the drawing room.

Miss Dashwood rose.

‘It is probably nothing more than the fatigue of having sat up to have her bed made,’ she said. ‘I will give her the cordials the apothecary supplied, and they will let her sleep.’

She left the room, and Mrs Jennings and I settled down to a hand of piquet.

‘Poor girl, I do not like the look of her,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘Mark my word, Colonel, she will get worse before she gets better.’

Her words proved prophetic. As I went upstairs when Mrs Jennings retired for the night, I heard a cry coming from the sick room: ‘Is Mama coming?’

I paused on the stairs, anxious at the feverish sound of her voice.

‘But she must not go round by London,’ cried Marianne, in the same hurried manner, ‘I shall never see her if she goes by London.’

A bell rang, and a maid hurried past me.

Recalled to myself, I went downstairs again, where I paced the length of the room, wishing there was something I could do to help. Another moment and Miss Dashwood entered.

‘I am anxious, nay, worried, very worried,’ she said, wringing her hands. ‘My sister is most unwell. If only my mother were here!’

At last! There was a way in which I could help.

‘I will fetch her. I will go instantly, and bring her to you at once,’ I said.

‘I cannot impose on you ...’ she began, with a show of reluctance.

‘It is no imposition, I assure you. I am only too glad to be able to help.’

‘Oh, thank you! Thank you,’ she said. ‘I do confess it would relieve my mind greatly if she were here.’

‘I will have a message sent to the apothecary at once, and I will be off as soon as the horses can be readied.’

The horses arrived just before twelve o’clock, and I set out for Barton to collect Mrs Dashwood and bring her to her daughter.

Monday 17 April

I arrived at Barton Cottage at about ten o’clock this morning, having stopped for nothing except to change horses, and braced myself for the ordeal to come. I knocked at the door. The maid answered it, and Mrs Dashwood appeared behind her, already dressed in her cloak.

Her hand flew to her chest as she saw me.

‘Marianne ...’ she said in horror.

‘Is alive, but very ill. Miss Dashwood has asked me to bring you to her.’

‘I am ready. I was about to set out, for I was alarmed by Elinor’s letter, no matter how much the tried to reassure me, and I wanted to be with Marianne. The Careys will be here at any minute to take care of Margaret, for I cannot take her into a house of infection, and as soon as they arrive, we will be on our way. But you are tired. You must have something to eat and drink.’

I shook my head, but she insisted, and as we had to wait for the Careys, I at last gave way. I ate some cold meat and bread, washed down with a glass of wine, and I felt better for it. The Careys arrived just as I was finishing my hasty meal.

‘Don’t you fret,’ said Mrs Carey to Mrs Dashwood. ‘I’ll take care of Miss Margaret. You go to Miss Marianne, my dear.’

‘Bless you,’ said Mrs Dashwood.

I escorted her out to the carriage, and we set off.

‘My poor Marianne, I should never have let her go to London alone,’ she said. ‘I should have gone with her, but I had no idea! I believed in Willoughby. He was well known and well liked in the neighbourhood. I never suspected ... I thought she would have such fun in London, but instead she found nothing but misery and mortification. And now this! Is she very ill?’

I could not deceive her, but I said that the apothecary was hopeful.

‘And Elinor? What does she think?’

‘That her sister will be more comfortable when you are at Cleveland.’

‘Then pray God we will soon be there. It is terrible, terrible. Oh, my poor Marianne! I should never have encouraged her attachment to Willoughby, but he seemed perfect in every way: young, handsome, well connected, lively; matching her in spirits and enthusiasms; sharing her taste in music, poetry, and everything else they discussed. They seemed made for each other. And yet he deceived her, abandoned her and married another. I should have made enquiries as soon as I saw her preference; I should have ascertained what kind of man he was, instead of relying on the assurances of Sir John which, though kindly meant, were based on nothing more than the fact that Willoughby was a fine sportsman and a good dancer. I should have asked her if they were engaged, instead of feeling I could not speak of it. I thought too much of her privacy and not enough of her health. Oh, what folly!’

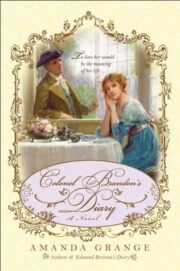

"Colonel Brandon’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.