The insolence! It was beyond anything. To speak to her in such a fashion, after the way he had behaved towards her at Barton!

She searched his eyes, as if unable to believe what was happening.

‘But have you not received my notes?’ she cried. ‘Here is some mistake, I am sure — some dreadful mistake. What can be the meaning of it? Tell me, Willoughby — for heaven’s sake, tell me, what is the matter?’

He made no reply; his complexion changed and all his embarrassment returned; but, on catching the eye of Miss Grey, he recovered himself again, and said, ‘Yes, I had the pleasure of receiving the information of your arrival in town, which you were so good as to send me.’

Then he turned hastily away with a slight bow and rejoined Miss Grey.

Marianne was white and stood as one stunned.

I thought, She is going to faint.

I stepped forward, but her sister was there before me and the carriage was sent for, and before very long she had left the house.

I did not linger. I was in no mood for entertainment after what I had just seen, and I was soon back at my club, where my heart was full of love and tenderness for Marianne and where I cursed the name of Willoughby.

Wednesday 25 January

I rose early, too restless to stay in bed, and went riding in the park. Having worked off the worst of my energy I went to Mrs Jennings’s house. I discovered that Marianne was resting, but I spoke to her sister and I soon found that they had learnt from Willoughby that he was engaged. He had written to Marianne pretending that he had never felt anything for her and saying that she must have imagined his regard. He had concluded by saying that he was engaged to Miss Grey and that they would soon be married.

‘That is abominable,’ I said. ‘Worse than I expected. And all this time he has let her suffer, knowing that his passion had cooled and that he had no intentions towards her.’

‘It is despicable, is it not?’ she said. ‘I would not have believed him capable of such a thing.’

‘He is capable of anything! And how is she?’

‘Her sufferings have been very severe: I only hope that they may be proportionably short. It has been, it is a most cruel affliction. Till yesterday, I believe, she never doubted his regard; and even now, perhaps — but I am almost convinced that he never was really attached to her. He has been very deceitful! ’

‘He has, indeed! But your sister does not consider it quite as you do?’

‘You know her disposition, and may believe how eagerly she would still justify him if she could.’

I wondered if I should tell her what I knew of Willoughby, but I did not know if it would bring her comfort or only distress her more, and in the end I left without speaking, to curse Willoughby and to love Marianne all the more.

Thursday 26 January

I was thinking over my dilemma this morning as I walked down Bond Street when I saw Mrs Jennings.

‘Well, Colonel! And what do you think of this business between Miss Marianne and Willoughby? I never was more deceived in my life. Poor thing! She looks very bad. No wonder. I can scarce believe it, but it is true. He is to be married very soon — a good-for-nothing fellow! I have no patience with him. Mrs Taylor told me of it, and she was told it by a particular friend of Miss Grey herself, else I am sure I should not have believed it; and I was almost ready to sink as it was. Well, said I, all I can say is that if it is true, he has used a young lady of my acquaintance abominably ill, and I wish with all my soul his wife may plague his heart out. And so I shall always say. I have no notion of men’s going on in this way: and if ever I meet him again, I will give him such a dressing down as he has not had this many a day. But there is one comfort, he is not the only young man in the world worth having; and with her pretty face she will never want admirers. There is a chance for you now, Colonel.’

Before I had a chance to reply, she went on, with scarcely a pause for breath.

‘Poor girl! She cried her heart out this morning, for a letter came from her mother and it was full of his perfections. Her mother, you see, believes them to be engaged. Ah, me! Miss Dashwood has a sad task before her, for she has to write to her mother and let her know how matters stand. Go to them, Colonel. You will do them good.’

My mind was made up. I would tell Marianne the truth. On arriving at the house I saw that Miss Dashwood, too, looked thinner than formerly; Willoughby’s perfidy was taking a toll on her as well as her sister.

‘I hope you do not mind me calling at such a time, but I met Mrs Jennings and she thought I would be welcome,’ I said. ‘I was the more easily encouraged to come because I thought that I might find you alone, which I was very desirous of doing. My object — my wish — my sole wish in desiring it — I hope, I believe it is — is to be a means of giving comfort — no, I must not say comfort — not present comfort — but conviction, lasting conviction to your sister’s mind. My regard for her, for yourself, for your mother — will you allow me to prove it, by relating some circumstances, which nothing but a very sincere regard — nothing but an earnest desire of being useful — though where so many hours have been spent in convincing myself that I am right, is there not some reason to fear I may be wrong?’

I stopped, for I was finding it more difficult than I had anticipated.

‘I understand you,’ she said. ‘You have something to tell me of Mr Willoughby that will open his character farther. Your telling it will be the greatest act of friendship that can be shown to Marianne. My gratitude will be ensured immediately by any information tending to that end, and hers must be gained by it in time. Pray, pray let me hear it.’

‘You shall; and, to be brief, when I quitted Barton last October — but this will give you no idea — I must go farther back. You will find me a very awkward narrator, Miss Dashwood; I hardly know where to begin. A short account of myself, I believe, will be necessary, and it shall be a short one. On such a subject,’ I said with a sigh, ‘I can have little temptation to be diffuse.’

I stopped a moment to gather my thoughts, and then I gave her an account of the whole: my love for Eliza, her marriage to my brother, her fall, her divorce, her child, and then her daughter’s disappearance.

‘I had no news of her for months, but she wrote to me last October,’ I said. ‘The letter was forwarded to me from Delaford, and I received it on the very morning of our intended party to Whitwell. Little did Mr Willoughby imagine, I suppose, that I was called away to the relief of one whom he had made poor and miserable; but had he known it, what would it have availed? Would he have been less gay or less happy in the smiles of your sister?’

‘This is beyond everything!’ exclaimed Miss Dashwood in horror, when I had told her the whole.

‘His character is now before you — expensive, dissipated, and worse than both. When I came to you last week and found you alone, I came determined to know the truth, though irresolute what to do when it was known. My behaviour must have seemed strange to you then, but now you will comprehend it. To suffer you all to be so deceived; to see your sister — but what could I do? I had no hope of interfering with success, and sometimes I thought your sister’s influence might yet reclaim him. But now, I only hope that she may turn with gratitude towards her own condition when she compares it with that of my poor Eliza.’

‘I am very grateful to you, Colonel, for having spoken. I have been more pained by her endeavours to acquit him than by all the rest, for it irritates her mind more than the most perfect conviction of his unworthiness can do. Now, though at first she will suffer much, I am sure she will soon become easier,’ she said with gratitude.

‘Thank you, you relieve my mind,’ I said.

‘Is Eliza still in town?’ she asked me kindly, showing a genuine interest in my dear Eliza’s fate.

‘No; as soon as she recovered from her lying-in, I removed her and her child into the country, and there she remains.’

Recollecting then that I was probably keeping Miss Dashwood from her sister, I left her, hoping that she could now give some solace to Marianne.

Friday 27 January

I called on Mrs Jennings today and was warmly received.

‘Ah, Colonel, you have done her good,’ were Mrs Jennings’s first words to me. ‘You have your chance, now. She is yours for a few kind words.’

I had thought about it over and over again, and although I wanted nothing more than to win her, I did not want to do so when she was weak and unable to resist. I wanted her love, not just her acquiescence, and she was in no condition to give it.

‘Oh, I know how it will be!’ she went on. ‘A summer wedding, and the two of you made happy.’

‘Please, I beg you, do not talk of it,’ I said, for I did not want her to distress Marianne.

‘We will all be talking of it soon!’ she said.

Fortunately, she was on her way out and so she could not talk about it any more.

I was announced, and when I went in, I saw Marianne sitting by the fire. I expected her to look disappointed at my arrival as she usually did, but instead she rose and came towards me with an expression of such sweet feeling that I was almost unmanned.

‘How good of you to call,’ she said, with a voice full of compassionate respect. ‘I never knew, never suspected, that you had had such a tragedy in your life. I always thought you a dry and soulless man. How easily we are deceived! And Eliza ... how is she?’

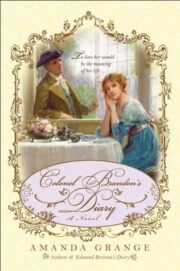

"Colonel Brandon’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.