Try as I might, I could not discover the meaning of it, until Mrs Jennings, seeing my eyes following Marianne, said to me, ‘Ah! You see how it is! Willoughby was here this morning, when we were out. He left his card and Miss Marianne found it on the table when we returned. She was vexed with herself for having left the house, and now she can settle to nothing in anticipation of seeing him tomorrow.’

So! He had left his card. Then he had not dropped the acquaintance. But what did he mean by it? If he was in love with her, why was he not with her? And if he was not in love with her, then why had he called?

And if his behaviour was perplexing to me, how much more perplexing must it be to Marianne?

As I watched her, I wished I could bring her some ease. But there was only one man who could do that, and that man was Willoughby.

Wednesday 18 January

I received a note from Sir John, telling me that he and his family were in town and inviting me to dine with them tomorrow, and I was glad to have something to take my thoughts from Marianne, for, where she is concerned, I feel helpless, and that is not a feeling I am used to. Nor is it a feeling I like.

Thursday 19 January

Sir John got up a dance after dinner this evening — a fact which displeased Mary, for she did not want it known that she had given such a small dance with only two violins and a sideboard collation — and I was hoping that it would put some life into Miss Marianne, but the music did little to rouse her, and although she danced, she did so without any spirit. After a while she sat out, saying that she had a headache. Her face looked grey, and what worried me more was that she did not look outwards, at the dancers, but inwards, at her own thoughts.

I hated to see her so cast down. It cut me to the quick. I was about to go over to her and see if I could cheer her, or at least distract her thoughts, when Sir John joined me, saying, ‘Ay, Miss Marianne’s in love all right! I cannot think what Willoughby is about! He should be here by now. I saw him this morning in the street and told him he must come along this evening. Once he arrives, she will be happy enough.’

I looked at her again and thought that she was pale because she was wondering why he did not come, but then I discovered that she did not even know that he had been invited.

I thought, If she looks so ill now, when she believes he is not a guest, how will she look when she learns that he was invited but did not come?

But no one enlightened her, for which I thank God, for I do not think she could have borne it.

And I — I can no longer bear it. Should I say something or should I remain silent? So much depends on whether she is engaged or not. If she is, I cannot speak, for she will not believe me. If not ...

Is there any hope for me? Is there a chance that I might yet win her?

Or must I resign myself to living without her?

I cannot sleep for thinking about it.

Tomorrow I must ask her sister and find out once and for all.

Friday 20 January

I rose early and was at Berkeley Street as soon as it was seemly.

I went in, and as soon as I did so, I saw the servant carrying a letter to Willoughby, addressed in Marianne’s hand.

I felt a cold wave wash over me. If they were openly corresponding, then there could be no doubt: they must be engaged.

Miss Dashwood greeted me kindly, but I could not concentrate on civilities, and I blurted out my thoughts, asking her when I was to congratulate her on having a brother and saying that news of her sister’s engagement was generally known.

‘It cannot be generally known,’ she returned in surprise, ‘for her own family does not know it.’

I was startled.

‘I beg your pardon,’ I said. ‘I am afraid my enquiry has been impertinent, but I had not supposed any secrecy intended, as they openly correspond, and their marriage is universally talked of. Is everything finally settled? Is it impossible to — ?’ And then I lost the last vestiges of my control and begged her, ‘Tell me if it is all absolutely resolved on; that any attempt — that in short, concealment, if concealment be possible, is all that remains.’

For I knew that if Marianne was indeed engaged, then I must endeavour to hide my own feelings and wish her happy.

Miss Dashwood hesitated before replying.

‘I have never been informed by themselves of the terms on which they stand with each other, but of their mutual affection I have no doubt,’ she said.

Their mutual affection. Nothing could have been plainer. I felt myself grow cold.

There was nothing left except for me to gather what remained of my dignity and to say, ‘To your sister I wish all imaginable happiness; to Willoughby that he may endeavour to deserve her.’

And then, unable to bear Miss Dashwood’s look of sympathy, I took my leave.

Their mutual affection.

The words rang in my ears.

It was worse than an engagement. An engagement might be ended, however unlikely that might be. But mutual affection ... I could not fight against that.

I had only one thing to fight against now, and that was despair.

Tuesday 24 January

I was disinclined for company this evening, but I could not sit at home and brood. I leafed through my invitations and set out for the Pargeters’ party, knowing that it would be well attended and that it would lift my spirits to be in company.

I saw some of my acquaintance there as I waited on the stairs to be received, which made the waiting tolerable. But on entering the drawing room, I received a shock, for there was Willoughby, and he was talking to a very fashionable young woman. From the way their heads were held close together, and the way he smiled at her, it was evident that she was no casual acquaintance, but that he was courting her.

But how could this be, when he was in love with Marianne?

‘Miss Grey is a lucky young woman, is she not?’ asked Mrs Pargeter, seeing the direction of my gaze. ‘Mr Willoughby is popular wherever he goes, and she has done well to catch him. They are well suited, fashionable people both, and with handsome fortunes, for though he has only a small income at present, he has expectations, and she is a considerable heiress with fifty thousand pounds. They make an attractive couple.’

‘A couple?’ I asked, with a peculiar feeling which was a mixture of elation and despair.

‘Yes, the marriage is to take place within a few weeks, and then they are to go to Combe Magna, his place in Somersetshire, where they intend to settle.’

I could not believe it, although why I could not, I did not know, for I had had every proof that he was not a gentleman. And yet this ... It was almost worse than what he had done to Eliza, for it was not thoughtless selfishness, it was wanton cruelty. He knew that Marianne was in town, for he had left his card and he must have received her letters. If he was really betrothed to Miss Grey, then why had he not written to Marianne and explained? It would have cost him nothing, demanded no sacrifice, as marriage to Eliza would have done. It would have taken him a few minutes, no more, and yet he had not even bothered to spend so small an amount of time to write to her and put her out of her misery.

He did not see me, for which I was grateful, for I could not have brought myself to acknowledge him. I was so sickened by his behaviour that I wanted to leave, but there was a crush of people coming up the stairs and it was impossible for me to force my way down them. I retired to the card room, therefore, to fume in silent rage, for it was evident that he had deserted Marianne as callously as he had deserted Eliza, with more cruelty, but — thank God! — to less ruinous effect.

After a few hands of cards I thought the crush would have abated and that I would be able to make my way down the stairs, and so I left the card-table and walked back into the saloon. As I entered it, my eye was drawn to a young woman just entering the room through the opposite door, and I saw that it was Marianne. She was looking very beautiful. Her eyes were bright and there was a spot of colour in each cheek which intensified her loveliness. Her dress was simple, but she needed no elaborate gown to set off her graceful figure. Her manner was animated and her gaze darted hither and hither, and I realized with dismay that she was looking for Willoughby.

At that moment she saw him, and her countenance glowed with delight. She began to move towards him, but her sister held her back, evidently fearing a scene, and guided her into a chair, where she sat in an agony of impatience which affected every feature as she waited for him to notice her.

At last he turned round and Marianne started up. Pronouncing his name in a tone of affection, she held out her hand to him. He approached, but slowly, and he addressed himself rather to Miss Dashwood than Marianne, talking to her as though they were nothing more than casual acquaintances, instead of intimate friends.

Marianne looked aghast.

‘Good God! Willoughby, what is the meaning of this?’ I heard her cry. ‘Have you not received my letters?’ And, as he stood with his hands resolutely behind his back, ‘Will you not shake hands with me?’

I saw him take her hand, but only because he could not avoid it, and heard him say, ‘I did myself the honour of calling in Berkeley Street last Tuesday, and very much regretted that I was not fortunate enough to find yourselves and Mrs Jennings at home. My card was not lost, I hope?’

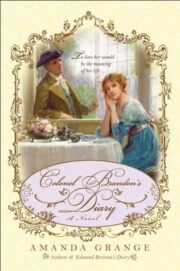

"Colonel Brandon’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.