‘She is not your mistress. She is a young girl of good family who has been cruelly deceived. I have been lenient with you in offering you a chance to marry her, but I confess that I am pleased you have refused, for I would not have liked to see her tied to a man of so little worth. If you will give me the name of your seconds, we will meet at a time and place of your choosing and settle this matter.’

‘Now look here, Brandon, you are a man of the world. Let us settle this as men of the world.’

‘That is what I am here to do.’

‘On the field of honour? Oh, come now, Brandon, you are making too much of it. I am sure she will be happy as long as she has an income. I am not rich, but I can give her something, I am sure. And then, when Mrs Smith dies and I inherit my fortune, I can give her something more. I will set her up in her own establishment, with a maid and everything comfortable.’

‘If you will not repair the damage you have done to her by marrying her, then you will name your seconds. Which is it to be?’

He protested, but as he was adamant that he would not marry her, there was only one course of action open to me.

Leaving him, I sought out some of my friends from my regiment. As luck would have it, Green and Wareham were in town. I made my way to their lodgings and I found them in their shirtsleeves, cleaning their pistols.

‘Brandon! Come in, man, come in,’ said Green, as he opened the door.

I went in, and found that Wareham, too, was at home.

‘Good to see you again, Brandon,’ he said, looking up from cleaning his gun.

‘And you.’

After the customary greetings, I said, ‘Gentlemen, I am not here on a social visit. I am in need of your help.’

They looked at me curiously and Green said, ‘That sounds serious.’

‘It is,’ I said, taking off my hat and gloves. ‘I need you to act as my seconds.’

They were immediately alert, and wanted to know all the details. As soon as I had satisfied them as to what had happened, they agreed at once to act for me.

‘The dog!’ said Green.

‘He should have been in the army. It would have taught him a sense of duty,’ said Wareham.

‘I would not have wanted a man like that in my regiment,’ I said, to which they both agreed.

‘You have challenged him already?’ asked Green.

‘Yes. I have just come from his lodgings.’

‘You know we will have to give him a chance to marry her?’ said Green. ‘There is a code of conduct in these things and we must stick to it, if we want to consider ourselves gentlemen. ’

‘Of course. I have already given him a chance and he told me he would not marry a penniless girl.’

Green’s face showed his disgust.

‘Nevertheless, we have to give him another chance,’ said Wareham.

‘As my seconds, I would expect you to do no less.’

‘What weapon do you think he will choose?’ asked Green with interest.

‘A pistol, I suspect. He probably fences, but I doubt if he has any experience with a sword.’

‘And will you agree to his choice?’

‘I will.’

‘Whatever it is?’

‘Whatever it is.’

‘He will be able to choose the ground,’ said Green.

‘Let him,’ I said. ‘It makes no difference to me where I fight him.’

‘Then we will go and see him now, and return as soon as possible,’ said Wareham, reaching for his coat.

They left me to kick my heels whilst they sought out Willoughby and returned just over an hour later.

‘Well?’ I demanded.

‘He still refuses to marry her. He says he would rather die at once than die a slow death being married to a woman with nothing to recommend her but a beauty which has now surely gone.’

‘It is a pity he did not think of that before he seduced her,’ I remarked. ‘And what weapon has he chosen?’

‘Pistols. The place to be Hounslow Heath, the time tomorrow at dawn.’

‘That suits me well.’

‘Where are you lodging?’

‘In St James’s Street.’

‘Then we will meet there in the morning and travel to the heath together.’

Saturday 5 November

I slept soundly and I was roused by my valet well before dawn. The morning was cold and I dressed with alacrity, eating a hearty breakfast before Green and Wareham called for me. I put on my coat, grateful for the warmth of its capes. Then, donning my hat and gloves, I went out into the mist-shrouded morning.

Lighted flambeaus pierced the gloom, their flames flickering fitfully as they strove to push back the dark, revealing the grey streets beyond.

I heard the muffled cry of the night watchman, ‘All’s well.’

‘All’s well for some,’ said Green, as I climbed into the carriage.

‘For us,’ I said. ‘I am ready to finish this business.’

‘Ay,’ said Wareham. ‘Let us be done with it.’

The carriage pulled away. The horses’ hoofs sounded strangely muted, and the turning of the wheels was no more than a grating whisper as the carriage bumped over the cobbles.

‘This damnable fog,’ said Green, peering out of the window. ‘I hope it clears by the time we reach the heath, or you will not be able to see each other, let alone fire.’

We were in luck. When we stepped out onto the heath, we could see for twenty paces, enough for our business.

There was no sign of Willoughby’s carriage.

Ten minutes later Willoughby arrived, attended by two men who looked nervous, as well they might. They were dandies, not soldiers, and had probably never been seconds in their lives.

‘I will give him another chance to change his mind,’ said Green.

He went over to Willoughby, they had words, and Green returned, saying, ‘The duel is to go ahead. It is for you to choose the distance, Brandon.’

That done, the seconds met in the middle and loaded the pistols in each other’s presence to ensure fair play, then Green and Wareham returned to hand me my weapon.

‘Willoughby’s man is to count the paces. After the count of ten, you may turn and fire at will. Is this agreeable to you? ’

‘It is.’

‘Then let us get it over with.’

I removed my coat. Across the heath, Willoughby removed his. The fog was lifting minute by minute, and I could see him clearly. We came together and stood back to back. His man counted the paces. One ... two ... three ... four ... five ... I thought of Eliza abandoned and left all alone ... six ... seven ... eight ... nine ...

‘Ten!’

I turned.

He turned, too, his arm already raised. He rushed his shot, firing without taking proper aim, and the bullet went wide, so wide I did not even feel it pass. He blanched, and dropped his arm. I saw his knees begin to buckle. I lifted my arm. And then he turned and I thought that he would run. But the horrified look on the faces of his seconds curtailed his cowardice, and he turned back towards me, white-faced and trembling, then turned sideways to present as small a target as possible.

For Eliza, I thought.

I took aim.

But as I did so, I saw not Willoughby and not Eliza, but Marianne. I imagined her face as she heard that Willoughby was dead; I imagined her grief, and I was horrified, for, if she was still enamoured of him, she would not grieve easily or quietly, but would suffer with all the depth of her being. If I killed him, I would cause her great pain, and with her nature, it was a pain she would not be certain of overcoming. And so I raised my arm and fired into the air.

Willoughby fell to his knees, and had to be assisted to his feet by his seconds.

I walked over to him and looked at him in disgust.

‘You are not worth shooting,’ I said.

Then Green brought me my coat, and we climbed into the carriage. It pulled away, jolting over the heath before turning on to the road.

We went back to Green’s and Wareham’s lodgings. By the time we reached them, a wind had sprung up, and it had driven most of the fog away, revealing a cold, clean light as a pale sun broke through the clouds.

‘You deloped,’ said Wareham, as we went inside. ‘Why?’

‘Because there is another young woman caught in Willoughby’s toils,’ I said, as I took off my outdoor clothes and threw myself into a chair, ‘and I feared that, if I killed him, she would love him for ever.’

‘Another one?’ said Wareham. ‘How many women does the fellow have?’

‘A face like that brings them fluttering like moths to a flame,’ said Green, as he sat down on the sofa, flinging his arm along the back of it.

‘Ay, I wish I had his handsome features,’ said Wareham, laughing, as he caught sight of his crooked nose and scarred cheek in the glass. ‘It would make a change. I would dearly love to have all the women dangling after me. I would parade myself through the ballroom and pretend not to notice them following me, then I would turn around, astonished, and smile, just so’ — he simpered — ‘and bow’ — he bowed low — ‘and consider which lucky lady to take onto the floor. And then consider which lucky lady to take into my bed!’

‘Whereas I do have his handsome features,’ said Green.

‘True, but in all the wrong places!’ said Wareham.

‘Brandon is the handsome one amongst us,’ said Green.

‘Which is like saying the clean one amongst chimney sweeps!’ said Wareham.

‘Perhaps he is handsome enough to win the lady for whom he spared Willoughby’s life,’ said Green.

‘I cannot think what you mean,’ I said.

‘No?’

‘No.’

They roared with laughter, and Green leapt on me and wrestled me to the ground.

‘Admit it!’ he said as he held me down.

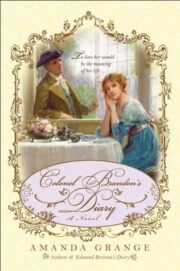

"Colonel Brandon’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.