"Well." I squared my shoulders. I wasn't sweaty anymore, after having so much wind blown on me, but I soon would be, if I stood on that hot sidewalk much longer. "Here goes nothing."

I opened the gate in the low chain-link fence that surrounded the house, and strode up the cement steps to the front door. I didn't realize Rob had followed me until I'd reached out to ring the bell.

"So what exactly," he said, as we listened to the hollow ringing deep inside the house, "is the plan here?"

I said, "There's no plan."

"Great." Rob's expression didn't change. "My favorite kind."

"Who is it?" demanded a woman's voice from behind the closed door. She didn't sound very happy about having been disturbed.

"Hello, ma'am?" I called. "Hi, my name is Ginger Silverman, and this is my friend, Nate. We're seniors at Chicago Central High School, and we're doing a research project on parental attitudes toward children's television programming. We were wondering if we could ask you a few questions about the kinds of television programs your children like to watch. It will only take a minute, and will be of invaluable help to us."

Rob looked at me like I was insane. "Ginger Silverman?"

I shrugged. "I like that name."

He shook his head. "Nate?"

"I like that name, too."

Inside the house, locks were being undone. When the door was thrown back, I saw, through the screen door, a tall, skinny woman in cutoffs and a halter top. You could tell she'd once taken care to color her hair, but that that had sort of fallen by the wayside. Now the ends of her hair were blonde, but the two inches of it at the top were dark brown. On her forehead, not quite hidden by her two-tone hair, was a dark, crescent-moon-shaped scab, about an inch and a half long. Out of one corner of her mouth, which was as flat and skinny as the rest of her, dangled a cigarette.

She looked at Rob and me as if we had dropped down from another planet and asked her to join the Galaxian Federation, or something.

"What?" she said.

I repeated my spiel about Chicago Central High School—who even knew if there was such a place?—and our thesis on children's television programming. As I spoke, a small child appeared from the shadows behind Mrs. Herzberg—if, indeed, this was Mrs. Herzberg, though I suspected it was—and, wrapping her arms around the woman's leg, blinked up at us with big brown eyes.

I recognized her instantly. Keely Herzberg.

"Mommy," Keely said curiously, "who are they?"

"Just some kids," Mrs. Herzberg said. She took her cigarette out of her mouth and I noticed that her fingernails were very bleedy-looking. "Look," she said to us. "We aren't interested. Okay?"

She was starting to close the door when I added, "There's a ten-dollar remuneration to all participants. . . ."

The door instantly froze. Then it swung open again.

"Ten bucks?" Mrs. Herzberg said. Her tired eyes, under that crescent-shaped scab, looked suddenly brighter.

"Uh-huh," I said. "In cash. Just for answering a few questions."

Mrs. Herzberg shrugged her skinny shoulders, and then, exhaling a plume of blue smoke at us through the screen door, she went, "Shoot."

"Okay," I said eagerly. "Um, what's your daughter's—this is your daughter, isn't it?"

The woman nodded without looking down. "Yeah."

"Okay. What is your daughter's favorite television show?"

"Sesame Street," said Mrs. Herzberg, while her daughter said, "Rugrats," at the same time.

"No, Mommy," Keely said, nagging on her mother's shorts. "Rugrats."

"Sesame Street," Mrs. Herzberg said. "My daughter is only allowed to watch public television."

Keely shrieked, "Rugrats!"

Mrs. Herzberg looked down at her daughter and said, "If you don't quit it, I'm sending you out back to play."

Keely's lower lip was trembling. "But you know I like Rugrats best, Mommy."

"Sweetheart," Mrs. Herzberg said. "Mommy is trying to answer these people's questions. Please do not interrupt."

"Um," I said. "Maybe we should move on. Do you and your husband discuss with one another the kinds of television shows your daughter is allowed to watch?"

"No," Mrs. Herzberg said shortly. "And I don't let her watch junk, like that Rugrats."

"But, Mommy," Keely said, her eyes filled with tears, "I love them."

"That's it," Mrs. Herzberg said. She pointed with her cigarette toward the back of the house. "Outside. Now."

"But, Mommy—"

"No," Mrs. Herzberg said. "That's it. I told you once. Now go outside and play, and let Mommy talk to these people."

Keely, letting out a hiccuppy little sob, disappeared. I heard a screen door slam somewhere in the house.

"Go on," Mrs. Herzberg said to me. Then her eyebrows knit. "Shouldn't you be writing my answers down?"

I reached up to smack myself on the forehead. "The clipboard!" I said to Rob. "I forgot the clipboard!"

"Well," Rob says. "Then I guess that's the end of that. Sorry to trouble you, ma'am—"

"No," I said, grabbing him by the arm and steering him closer to the screen door. "That's okay. It's in the car. I'll just go get it. You keep asking questions while I go and get the clipboard."

Rob's pale blue eyes, as he looked down at me, definitely had ice chips in them, but what was I supposed to do? I went, "Ask her about the kind of programming she likes, Nate. And don't forget the ten bucks," and then I bounded down the steps, through the overgrown yard, out the gate …

And then, when I was sure Rob had Mrs. Herzberg distracted, I darted down the alley alongside her house, until I came to a high wooden fence that separated her backyard from the street.

It only took me a minute to climb up onto a Dumpster that was sitting there, and then look over that fence into the backyard.

Keely was there. She was sitting in one of those green plastic turtles people fill with sand. In her hand was a very dirty, very naked Barbie doll. She was singing softly to it.

Perfect, I thought. If Rob could just keep Mrs. Herzberg busy for a few minutes …

I clambered over the fence, then dropped over the other side into Keely's yard. Somehow, in spite of my gymnast-like grace and James Bondian stealthiness, Keely heard me, and squinted at me through the strong sunlight.

"Hey," I said as I ambled over to her sandbox. "What's up?"

Keely stared at me with those enormous brown eyes. "You aren't supposed to be back here," she informed me gravely.

"Yeah," I said, sitting down on the edge of the sandbox beside her. I'd have sat in the grass, but like in the front yard, it was long and straggly-looking, and after my recent tick experience, I wasn't too anxious to encounter any more bloodsucking parasites.

"I know I'm not supposed to be back here," I said to Keely. "But I wanted to ask you a couple of questions. Is that okay?"

Keely shrugged and looked down at her doll. "I guess," she said.

I looked down at the doll, too. "What happened to Barbie's clothes?"

"She lost them," Keely said.

"Whoa," I said. "Too bad. Think your mom will buy her some more?"

Keely shrugged again, and began dipping Barbie's head into the sandbox, stirring the sand like it was cake batter, and Barbie was a mixer. The sand in the sandbox didn't smell too fresh, if you know what I mean. I had a feeling some of the neighborhood cats had been there a few times.

"What about your dad?" I asked her. "Could your dad buy you some more Barbie clothes?"

Keely said, lifting Barbie from the sand and then smoothing her hair back, "My daddy's in heaven."

Well. That settled that, didn't it?

"Who told you that your daddy is in heaven, Keely?" I asked her.

Keely shrugged, her gaze riveted to the plastic doll in her hands. "My mommy," she said. Then she added, "I have a new daddy now." She wrenched her gaze from the Barbie and looked up at me, her dark eyes huge. "But I don't like him as much as my old daddy."

My mouth had gone dry … as dry as the sand beneath our feet. Somehow I managed to croak, "Really? Why not?"

Keely shrugged and looked away from me again. "He throws things," she said. "He threw a bottle, and it hit my mommy in the head, and blood came out, and she started crying."

I thought about the crescent-shaped scab on Mrs. Herzberg's forehead. It was exactly the size and shape a bottle, flying at a high velocity, would make.

And that, I knew, was that.

I guess I could have gotten out of there, called the cops, and let them handle it. But did I really want to put the poor kid through all that? Armed men knocking her mother's door down, guns drawn, and all of that? Who knew what the mother's bottle-throwing boyfriend was like? Maybe he'd try to shoot it out with the cops. Innocent people might get hurt. You don't know. You can't predict these things. I know I can't, and I'm the one with the psychic powers.

And yeah, Keely's mother seemed like kind of a freak, protesting that her kid only watches public television while standing there filling that same kid's lungs with carcinogens. But hey, there are worse things a parent could do. That didn't make her an unfit mother. I mean, it wasn't like she was taking that cigarette and putting it out on Keely's arm, like some parents I've seen on the news.

But telling the kid her father was dead? And shacking up with a guy who throws bottles?

Not so nice.

So even though I felt like a complete jerk about it, I knew what I had to do.

I think you'd have done the same thing, too, in my place. I mean, really, what else could anybody have done?

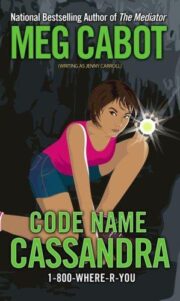

"Code Name Cassandra" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Code Name Cassandra". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Code Name Cassandra" друзьям в соцсетях.