"What's a guy doing," Rob wanted to know, "working at a band camp for little kids? They let guys do that?"

"Well, sure," I said. "Why not? Hey, wait a minute." I squinted up at Dave. Even though it wasn't quite nine yet, you could tell from the way the sun was beating down that it was going to be a scorcher. "Hey, Dave," I called. "You got a car, right?"

"Yeah," Dave said. "Why? You planning on staging a breakout?"

Into the phone, I said, "You know what, Rob? I think I—"

But Rob was already talking. And what he was saying, I was surprised to hear, was, "I'll pick you up at one."

I went, totally confused, "You'll what? What are you talking about?"

"I'll be there at one," Rob said again. "Where will you be? Give me directions."

Bemused, I gave Rob directions, and agreed to meet him at a bend in the road just past the main gates into the camp. Then I hung up, still wondering what had made him change his mind.

I trudged up the steps to where Dave stood, and handed him back his phone.

"Thanks," I said. "You're a lifesaver."

Dave shrugged. "You really need a ride somewhere?"

"Not anymore," I said. "I—"

And that's when it hit me. Why Rob had been so blasé about my going away for seven weeks, and why, just now on the phone, he'd changed his mind about coming up:

He hadn't thought there'd be guys here.

Seriously. He'd thought it was just going to be me and Ruth and about two hundred little kids, and that was it. It had never occurred to him there might be guys my own age hanging around.

That was the only explanation I could think of, anyway, for his peculiar behavior.

Except, of course, that explanation made no sense whatsoever. Because for it to be true, it would mean Rob would have to like me, you know, that way, and I was pretty sure he didn't. Otherwise, he wouldn't care so much about his stupid probation officer, and what he has to say on the matter.

Then again, the prospect of jail is a pretty daunting one. . . .

"Jess? Are you all right?"

I shook myself. Dave was staring at me. I had drifted off into Rob Wilkins dreamland right in front of him.

"Oh," I said. "Yeah. Fine. Thanks. No, I don't need a ride anymore. I'm good."

He slipped his cell phone back into his pocket. "Oh. Okay."

"You know what I do need, though, Dave?" I asked.

Dave shook his head. "No. What?"

I took a deep breath. "I need someone to keep an eye on my kids this afternoon," I said, in a rush. "Just for a little while. I, um, might be tied up with something."

Dave, unlike Ruth, didn't give me a hard time. He just shrugged and went, "Sure."

My jaw sagged. "Really? You don't mind?"

He shrugged again. "No. Why should I mind?"

We started back toward the dining hall. As we approached it, I noticed most of the residents of Birch Tree Cottage had finished breakfast and were outside, gathered around one of the campground dogs.

"It's a grape," Shane was saying, conversationally, to Lionel. "Go ahead and eat it."

"I do not believe it is a grape," Lionel replied. "So I do not think I will, thank you."

"No, really." Shane pointed at something just beneath the dog's ear. "In America, that's where grapes grow."

When I got close enough, of course, I saw what it was they were talking about. Hanging off one of the dog's ears was a huge, blood-engorged tick. It did look a bit like a grape, but not enough, I thought, to fool even the most gullible foreigner.

"Shane," I said, loudly enough to make him jump.

"What?" Shane widened his baby blues at me innocently. "I wasn't doing anything, Jess. Honest."

Even I was shocked at this bold-faced lie. "You were so," I said. "You were trying to make Lionel eat a tick."

The other boys giggled. In spite of the fright Shane had gotten the night before—and I had ended up letting him sleep inside; even I wasn't mean enough to make him sleep on the porch after the whole Paul Huck thing—he was back to his old tricks.

Next time, I was going to make him spend the night on a raft in the middle of the lake, I swear to God.

"Apologize," I commanded him.

Shane said, "I don't see why I should have to apologize for something I didn't do."

"Apologize," I said, again. "And then get that tick off that poor dog."

This was my first mistake. I should have removed the tick myself.

My second mistake was in turning my back on the boys to roll my eyes at Dave, who'd been watching the entire interaction with this great big grin on his face. Last night, he and Scott had confided to me that all the other counselors had placed bets on who was going to win in the battle of wills between Shane and me. The odds were running two to one in Shane's favor.

"Sorry, Lie-oh-nell," I heard Shane say.

"Make sure you mention this," I said, to Dave, "to your—"

The morning air was pierced by a scream.

I spun around just in time to see Lionel, his white shirt now splattered with blood, haul back his fist and plunge it, with all the force of his sixty-five pounds or so, into Shane's eye. He'd been aiming, I guess, for the nose, but missed.

Shane staggered back, clearly more startled by the blow than actually hurt by it. Nevertheless, he immediately burst into loud, babyish sobs, and, both hands pressed to the injured side of his face, wailed in a voice filled with shock and outrage, "He hit me! Jess, he hit me!"

"Because he make the tick explode on me!" Lionel declared, holding out his shirt for me to see.

"All right," I said, trying to keep my breakfast down. "That's enough. Get to class, both of you."

Lionel, horrified, said, "I cannot go to class like this!"

"I'll bring you a new shirt," I said. "I'll go back to the cabin and get one and bring it to you while you're in music theory."

Mollified, the boy picked up his flute case and, with a final glare in Shane's direction, stomped off to class.

Shane, however, was not so easily calmed.

"He should get a strike!" he shouted. "He should get a strike, Jess, for hitting me!"

I looked at Shane like he was crazy. I actually think that at that moment, he was crazy.

"Shane," I said. "You sprayed him with tick blood. He had every right to hit you."

"That's not fair," Shane shouted, his voice catching on a sob. "That's not fair!"

"For God's sake, Shane," I said, with some amusement. "It's a good thing you went to orchestra camp instead of football camp this summer, if you're gonna cry every time someone pokes you in the eye."

This had not, perhaps, been the wisest thing to say, under the circumstances. Shane's face twisted with emotion, but I couldn't tell if it was embarrassment or pain. I was a little shocked that I'd managed to hurt his feelings. It was actually kind of hard to believe a kid like Shane had feelings.

"I didn't choose to come to this stupid camp," Shane roared at me. "My mother made me! She wouldn't let me go to football camp. She was afraid I'd hurt my stupid hands and not be able to play the stupid flute anymore."

I dried up, hearing this. Because suddenly, I could see Shane's mother's point of view. I mean, the kid could play.

"Shane," I said gently. "Your mom's right. Professor Le Blanc, too. You have an incredible gift. It would be a shame to let it go to waste."

"Like you, you mean?" Shane asked acidly.

"What do you mean?" I shook my head. "I'm not wasting my gift for music. That's one of the reasons I'm here."

"I'm not talking," Shane said, "about your gift for music."

I stared at him. His meaning was suddenly clear. Too clear. There were still people, of course, standing nearby, watching, listening. Thanks to his theatrics, we'd attracted quite a little crowd. Some of the kids who hadn't made it to the music building yet, and quite a few of the counselors, had gathered around to watch the little drama unfolding in front of the dining hall. They wouldn't, I'm sure, know what he was referring to. But I did. I knew.

"Shane," I said. "That's not fair."

"Yeah?" He snorted. "Well, you know what else isn't fair, Jess? My mom, making me come here. And you, not giving Lionel a strike!"

And with that, he took off without another word.

"Shane," I called after him. "Come back here. I swear, if you don't come back here, it's the porch with Paul Huck for you tonight—"

Shane stopped, but not because I'd intimidated him with my threat. Oh, no. He stopped because he'd fun smack into Dr. Alistair, the camp director, who—having apparently heard the commotion from inside the dining hall, where he often sat after all the campers were gone and enjoyed a quiet cup of coffee—had come outside to investigate.

"Oof," Dr. Alistair said, as Shane's mullet head sank into his midriff. He reached down to grasp the boy by the shoulders in an attempt to keep them both from toppling over. Shane was no lightweight, you know.

"What," Dr. Alistair asked, as he steered Shane back around toward me, "is the meaning of all this caterwauling?"

Before I could say a word, Shane lifted his head and, staring up at Dr. Alistair with a face that was perfectly devoid of tears—but upon which there was an unmistakable bruise growing under one eye—said, "A boy hit me and my counselor didn't do anything, Dr. Alistair." He added, with a hiccupy sob, "If my dad finds out about this, he's going to be plenty mad, boy."

Dr. Alistair glared at me from behind the lenses of his glasses. "Is this true, young lady?" he demanded. He only called me young lady, I'm sure, because he couldn't remember my name.

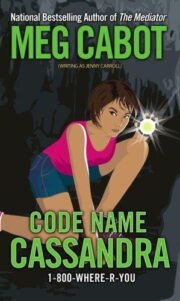

"Code Name Cassandra" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Code Name Cassandra". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Code Name Cassandra" друзьям в соцсетях.