I suppose I did know that, somewhere deep in the recesses of my mind. Lake Wawasee was private property. You had to be on a list of invited guests even to be let through the gates. They took security very seriously at Camp Wawasee, due to the number of expensive instruments lying around. Oh, and the kids, and all.

I looked from Pamela to Mr. Herzberg and then back again. They both looked … well, flushed. There was no other way to put it.

"Do you two know each other or something?" I asked.

Pamela, who was by no means what you'd call a shrinking violet kind of gal, actually blushed.

"No, no," she said. "I mean … well, we just met. Mr. Herzberg … well, Jess, Mr. Herzberg—"

I could see I was going to get nothing rational out of Miss J Crew. I decided to tackle Mr. L.L. Bean, instead.

"All right," I said, eyeing him. "I'll bite. If you're not a reporter, what do you want with me?"

Jonathan Herzberg wiped his hands on his khaki pants. He must have been sweating a lot or something, since he left damp spots on the cotton.

"I was hoping," he said softly, "that you could help me find my little girl."

C H A P T E R

6

I looked quickly at Pamela. She hadn't taken her eyes off Jonathan Herzberg.

Great. Just great. Mary Ann was in love with the Professor.

"Maybe you didn't hear me the first time," I said. "I don't do that anymore."

A lie, of course. But he didn't know that.

Or maybe he did.

Mr. Herzberg said, "I know that's what you told everyone. Last spring, I mean. But I … well, I was hoping you only said that because the press and everything … well, it got a little intense."

I just looked at him. Intense? He called being chased by government goons with guns intense?

I'd show him intense.

"Hello?" I said. "What part of 'I can't help you' don't you understand? It doesn't work anymore. The psychic thing is played out. The batteries have run dry—"

As I'd been speaking, Mr. Herzberg had been digging around in his briefcase. When he stood up again, he was holding a photograph.

"This is her," he said, thrusting the photo into my hands. "This is Keely. She's only five—"

I backed away with about as much horror as if he'd put a snake, and not a photo of a little girl, into my fingers.

"I'm not looking at this," I said, practically heaving the photo back at him. "I won't look at this."

"Jess!" Pamela sounded a little horrified herself. "Jess, please, just listen—"

"No," I said. "No, I won't. You can't do this. I'm out of here."

Look, I know how it sounds. I mean, here was this guy, and he seemed sincere. He seemed like a genuinely distraught father. How could I be so cold, so unfeeling, not to want to help him?

Try looking at it from my point of view: It is one thing to get a package in the mail with all the details of a missing child's case laid neatly out in front of one … to wake the next morning and make a single phone call, the origins of which the person on the receiving end of that call has promised to erase. Easy.

More than just easy, though: Anonymous.

But it is another thing entirely to have the missing kid's parent in front of one, desperately begging for help. There is nothing easy about that.

And nothing in the least anonymous.

And I have to maintain my anonymity. I have to.

I turned and headed for the door. I was going to say, I staggered blindly for the door, because that sounds all dramatic and stuff, but it isn't true, exactly. I mean, I wasn't exactly staggering—I was walking just fine. And I could see and all. The way I know I could see just fine was that the photo, which I thought I'd gotten rid of, came fluttering down from the air where I'd thrown it. Just fluttered right down, and landed at my feet. Landed at my feet, right in front of the door, like a leaf or a feather or something that had fallen from the sky, and just randomly picked me to land in front of.

And I looked. It landed faceup. How could I help but look?

I'm not going to say anything dorky like she was the cutest kid I'd ever seen or something like that. That wasn't it. It was just that, until I saw the photo, she wasn't a real kid. Not to me. She was just something somebody was using to try to get me to admit something I didn't want to.

Then I saw her.

Look, I was not trying to be a bitch with this whole not-wanting-to-help-this-guy thing. Really. You just have to understand that since that day, that day I'd been struck by lightning, a lot of things had gotten very screwed up. I mean, really, really screwed up. My brother Douglas had had to be hospitalized again on account of me. I had practically ruined this other kid's life, just because I'd found him. He hadn't wanted to be found. I had had to do a lot of really tricky stuff to make everything right again.

And I'm not even going to go into the stuff about the Feds and the guns and the exploding helicopter and all.

It was like that day the lightning struck me, it caused this chain reaction that just kept getting more and more out of control, and all these people, all of these people I cared about, got hurt.

And I didn't want that to happen again. Not ever.

I had a pretty good system in the works, too, for seeing that it didn't. If everyone just played along the way they were supposed to, things went fine. Lost kids, kids who wanted to be found, got found. Nobody hassled me or my family. And things ran along pretty damn smoothly.

Then Jonathan Herzberg had to come along and thrust his daughter's photo under my nose.

And I knew. I knew it was happening all over again.

And there wasn't anything I could do to stop it.

Jonathan Herzberg was no dope. He saw the photo land. And he saw me look down.

And he went in for the kill.

"She's in kindergarten," he said. "Or at least, she would be starting in September, if … if she wasn't gone. She likes dogs and horses. She wants to be a veterinarian when she grows up. She's not afraid of anything."

I just stood there, looking down at the photo.

"Her mother has always been … troubled. After Keely's birth, she got worse. I thought it was post-partum depression. Only it never went away. The doctors prescribed antidepressants. Sometimes she took them. Mostly, though, she didn't."

Jonathan Herzberg's voice was even and low. He wasn't crying or anything. It was like he was telling a story about someone else's wife, not his own.

"She started drinking. I came home from work one day, and she wasn't there. But Keely was. My wife had left a three-year-old child home, by herself, all day. She didn't come home until around midnight, and when she did, she was drunk. The next day, Keely and I moved out. I let her have the house, the car, everything … but not Keely." Now his voice started to sound a little shaky. "Since we left, she—my ex-wife—has just gotten worse. She's fallen in with this guy … well, he's not what you'd call a real savory character. And last week the two of them took Keely from the day care center I put her in. I think they're somewhere in the Chicago area—he has family around there—but the police haven't been able to find them. I just … I remembered about you, and I … I'm desperate. I called your house, and the person who answered the phone said—"

I bent down and picked the photo up. Up close, the kid looked no different than she had from the floor. She was a five-year-old little girl who wanted to be a veterinarian when she grew up, who lived with a father who obviously had as much of a clue as I did about how to braid hair, since Keely's was all over the place.

"He's got the custody papers," Pamela said to me softly. "I've seen them. When he first showed up … well, I didn't know what to do. You know our policy. But he … well, he …"

I knew what he had done. It was right there on Pamela's face. He had played on her natural affection for children, and on the fact that he was a single dad who was passably good-looking, and she was a woman in her thirties who wasn't married yet. It was as clear as the whistle around her neck.

I don't know what made me do it. Decide to help Jonathan Herzberg, I mean, in spite of my suspicion that he was an undercover agent, sent to prove I'd lied when I'd said I no longer had any psychic powers. Maybe it was the frayed condition of his cuffs. Maybe it was the messiness of his daughter's braids. In any case, I decided. I decided to risk it.

It was a decision that I'd live to regret, but how was I to know that then?

I guess what I did next must have startled them both, but to me, it was perfectly natural. Well, at least to someone who's seen Point of No Return as many times as I have.

I walked over to the radio I'd spied next to Pamela's desk, turned it on very loud, then yelled over the strains of John Mellencamp's latest, "Shirts up."

Pamela and Jonathan Herzberg exchanged wide-eyed glances. "What?" Pamela asked, raising her voice to be heard over the music.

"You heard me," I yelled back at her. "You want my help? I need to make sure you're legit."

Jonathan Herzberg must have been a pretty desperate man, since, without another word, he peeled off his sports coat. Pamela was slower to untuck her Camp Wawasee oxford T.

"I don't understand," she said as I went around the office, feeling under countertops and lifting up plants and the phone and stuff and looking underneath them. "What's going on?"

Jonathan was a little swifter. He'd completely unbuttoned his shirt, and now he held it open, to show me that nothing was taped to his surprisingly hairless chest.

"She wants to make sure we're not wearing wires," he explained to Pamela.

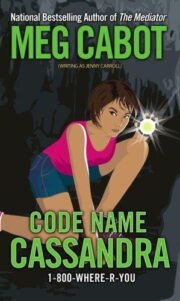

"Code Name Cassandra" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Code Name Cassandra". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Code Name Cassandra" друзьям в соцсетях.