But he was not being civil. She had lied when she said that. She knew that he was being anything but civil. Apart from those few words they had exchanged at the very start, he had made no attempt whatsoever to make conversation, and she had been feeling too tense to do so. And yet he had not taken his eyes off her. She had known it though for most of the time she had not had the courage to look up into his eyes.

Had he been gazing at her because he was wearing the willow for her, as Mrs. Summerberry had put it? No. She knew the answer was no. There had been a deliberate intent to embarrass her, to discompose her.

He had almost succeeded. She had almost cracked at the end and had looked up at him, determined to confront him, to demand an explanation of his behavior. But she had looked into his eyes, those keen gray eyes over which his eyelids drooped incongruously, giving an impression of sleepiness to an expression that was far from sleepy, and she had lost her nerve.

She had suddenly been even more intensely aware than she had been since the start of the waltz of his physical presence, of his great height and that impression of strength in his lean body that she was sure was no illusion, of some

force-some quite unnameable force-that terrified her now even more than it had used to do.

For whereas eight years before she had considered him cold and unfeeling and had been afraid of being trapped in a marriage with a man she feared, now she could sense a very real animosity in him and felt like a weak victim being stalked by a bird of prey.

It was a foolish idea, a ridiculous idea. And yet, she thought as she rubbed a cloth hard over her face and neck, it had haunted her through what had remained of the night after she had arrived home. It had kept her from sleep.

At luncheon, which she and Amy took with the children, Judith announced that they would walk to St. James's Park that afternoon for a change.

"And the river tomorrow," she said. "We will see if it is safe to walk upon."

Judith was feeling pleased with herself when they arrived back from their walk in St. James's. She could not be at all sure, of course, that the Marquess of Denbigh had ridden in Hyde Park that day, but if he had-and she had a strange feeling that he had-then he would have been foiled. He would have taken a lone and chilly ride for nothing.

She hoped that he had ridden there. Perhaps he would have realized by now that she could not so easily be made his victim.

And it was strange, she thought, repairing the damage made to her hair by her bonnet before going downstairs to the drawing room for tea, how she was assuming that the meeting in the park the afternoon before had been no accident. But how could it not have been? How could he have known?

The thought made her shiver. It was time for tea.

"We must buy some holly and ivy and other greenery," Amy was saying to the children, who were also in the drawing room for tea, as had been their custom since arriving in town. "And how dreadful to be talking about buying when they have always been there for the gathering in the country. But never mind. And we will need some bows and bells and other decorations."

"We are going to buy them?" Rupert asked.

Amy frowned. "We must make as many as possible," she said. "It will be far more fun. There are boxes and boxes of decorations at Ammanlea. Here we must begin with nothing. But it will be fun, I promise you children. Perhaps we can even make a Nativity scene somehow." She smiled brightly.

"Perhaps after we have been down to the river tomorrow,'' Judith said, "we can go shopping and buy some length of ribbon to start making the bows and streamers. Shall we, Kate?"

The child's eyes grew round with wonder.

"I still think Christmas is going to be dull with no one else to play with," Rupert said dubiously.

Judith smiled determinedly. "We will play with one another," she said. "And there will be so many good things to eat and only the four of us to eat them that we will all burst and never be able to play again."

"We must sing carols while we make the decorations," Amy said. "I wonder if we could go carol singing about the square, Judith. Do you think the people here would think we had quite lost our senses? I will miss going caroling more than anything else."

Amy had a sweet voice and was always the most valued member of the carolers who traveled about the neighborhood at Ammanlea every Christmas. She would be missed that year.

"Perhaps," Judith said, but was interrupted by the appearance of her father's butler, who had come into the room to announce the arrival of a gentleman below asking if he might call upon Mrs. Easton and Miss Easton.

"Upon me too?" Amy said, brightening.

"The Marquess of Denbigh, ma'am," the butler said, inclining his head stiffly.

"We are from home," Judith said.

“Oh, famous,'' Rupert said, jumping to his feet. "Perhaps he has come to give me another ride, Mama."

"Riding," Kate said, clapping her hands.

"Oh, how very civil of him," Amy said. "Do show him up." But she flushed and looked at her sister-in-law. "I am sorry. Judith?"

Judith felt rather as if someone had punched her in the ribs. "He is calling on both of us?" she asked. "Then please show him up, Mr. Barta."

"Famous," Rupert said. "I think he is top of the trees, Mama."

Another of Maurice's phrases.

Kate moved from her chair to sit on the stool at Judith's feet. Judith stood.

"Good afternoon, my lord," she said, clasping her hands before her when he entered the room.

Amy swept him a deep curtsy and beamed at him. "How very civil of you to call, my lord," she said. "It is quite as cold outside today as it was yesterday, is it not?"

"It is indeed, ma'am," he said. "But I am afraid I played coward today and called out my carriage."

"Good afternoon, my lord," Rupert said.

Kate half hid behind Judith's skirt.

"Ah, the children are here too," the marquess said. "And good day to you, sir, and to the young lady who believes that she is invisible although I can clearly see two large eyes and some auburn curls."

Kate chuckled and hid completely behind Judith.

"Won't you be seated, my lord?" Judith said coolly. "The tea tray arrived a mere few minutes before you. I have not even poured yet."

"Then my timing is perfect," he said, seating himself as Amy resumed her place. "I came to assure myself that you have recovered from the exertions of last night's ball, ma'am."

"Yes, I thank you," Judith said. "It was a very pleasant evening."

He looked penetratingly at her while she looked coolly back. She scorned to lower her eyes in her own drawing room.

"And to assure myself that you took no chill from your walk in the park yesterday, ma'am," he said, turning his attention to Amy.

"Oh, no," Amy said. "We walk every day, you know. And it is my opinion that it is fresh air and exercise that keeps a person healthy and free of chills. Huddling by a fire all day and every day is a quite unhealthy practice."

"My feelings exactly, ma'am," he said. "But sometimes it is very hard to resist the temptation to keep oneself warm and cozy."

"It is a hard winter we are having so far," Amy said. “My only hope is that the snow will not come to prevent travel before Christmas. There will be many disappointed families, I am afraid, if their members cannot journey to be together.''

"Yes, indeed," he said. "I have some guests coming to my home in Sussex for the holiday. I do not have any close family, but even so I will be hoping that both my guests and I will be able to travel. Loneliness is always hardest at Christmas for some reason."

"Yes," Amy said. "I remember…"

And to Judith's amazement they were off on a comfortable and lengthy coze, the two of them, ignoring her just as if she did not exist. And his manner with Amy was easy and pleasant, though of course he came nowhere near smiling.

She was angry. And even more so when Rupert, his cake eaten, got to his feet and went to stand patiently beside the marquess's chair, waiting to be noticed. She tried to frown him back to his own place, but he did not look her way.

"And how are you today, sir?" the marquess asked eventually, he and Amy having finally come to a full agreement about the undesirability of being alone at Christmas.

"My grandpapa keeps the largest stable in Lincolnshire," Rupert said gravely. "And the largest kennels too. My papa would have taught me to ride but he died before I was old enough. Uncle Maurice was too busy last summer, but he will teach me when he has time. I am going to be a bruising rider."

The marquess set a hand on the boy's shoulder while Judith unconsciously held her breath. "I have no doubt of it," he said. "You sat Pegasus quite fearlessly yesterday."

Rupert almost visibly swelled with pride.

"I was not afraid either," an indignant little voice said from the stool at Judith's feet.

He looked across the room, his eyes touching on Judith for the first time for many minutes before dropping to Kate.

"I don't believe," he said, "I have ever seen a lady sit a horse with such quiet dignity."

Judith could not see Kate's reaction to his words. The child said nothing, but Amy was beaming down at her.

Everyone was having a perfectly amicable good time, she thought, controlling her anger and sipping on her tea. And if she had been furious the evening before at the way he had gazed so fixedly at her for an hour or longer, now she was indignant at the way he had so effectively ignored her almost from the moment of his entrance into her father's drawing room-her drawing room in her father's absence.

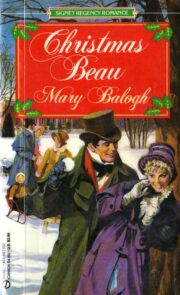

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.