And in Andrew's family, too, it was always a big occasion. It was traditional for the whole family to gather together at Ammanlea, and she had been expected to join them after her marriage and abandon her own family's traditions. She had always hated it. Almost the only activities had ever been card playing and heavy drinking.

Even last year. They had all been in deep mourning for Andrew and the nursery had been the only room in the house to be decorated. But the drinking and the card playing had gone on unabated despite the blackness and the gloom of all their clothing.

She had come almost to hate Christmas for seven years.

"We must decorate the house," she said. "We must find a way of celebrating and making Christmas a joyous occasion for the children, Amy, even though there will be just the four of us and the servants.'' She looked at her sister-in-law with some concern. "Are you sure you do not want to go home, Amy? You have never been away at Christmas, have you?"

"I am sure." Amy smiled. "I will miss all the children. I must admit that. But there are some things I will not miss, Judith. It will be lovely to be quiet with you and Rupert and Kate. Yes, we will decorate the house and go to church and sing carols. Perhaps carolers will come to the house. Does that happen in London, I wonder? It would be very pleasant, would it not?"

Yes, it would be pleasant, Judith thought. Strangely, although the prospect of their very small gathering seemed somewhat bleak, she was looking forward to Christmas for the first time in many years.

Invitations continued to arrive at the house daily. She could if she wished, she knew, be very busy and very gay all over Christmas. And she was determined to go out, to meet society again, to enjoy herself, to feel young again, of some worth again. But not too much. She would not sacrifice her children's happiness at Christmas for her own. And she would not leave Amy at home night after night while she abandoned herself to a life of gaiety.

Besides, she was a little afraid to go out. In some ways she was dreading that evening's ball. Would he be there again? she wondered.

It was a question she tried not to ask herself. There was no way of knowing the answer until the evening came. And even if he were, she told herself, it would not matter. For that very awkward first meeting was over, and they had had nothing whatsoever to say to each other and would be at some pains to avoid each other forever after.

There was no reason for the sleeplessness and the vivid, bizarre dreams of the past two nights and the breathless feeling of something like terror whenever her thoughts touched on him.

It was all eight years in the past. They had grown up since

then-though he, of course, had been her present age at the time it had happened. And they were civilized beings. There was no reason to wonder why he had made no effort to make conversation when they had been awkwardly stranded together at Lady Clancy's. It was merely that he was morose by nature, as he always had been. It was absurd to feel that she should have rushed into some explanation, some apology.

It had been a shock to realize that it had been the first time she had set eyes on him since that night of the opera, when her flight with Andrew had already been planned for the following day. That night she had sat through the whole performance without once concentrating on it, anxious about the plans for the morrow, breathless with the knowledge that the viscount, seated slightly behind her in the box, had been watching her more than the performance with those hooded and steely eyes. And she remembered wondering if he suspected, if he would do something to foil her plans, something to force her into staying with him and marrying him after all.

"He is slowing down," Amy said, and Judith realized with a jolt that her sister-in-law had been commenting on the approach of a rider and expressing the hope that he would not gallop too close to the children.

And looking up, Judith felt that disconcerting somersaulting of her stomach again. The rider, with a billowing black cloak, drew his equally black stallion to a halt, removed his beaver hat, and sketched them a bow.

"Mrs. Easton," the Marquess of Denbigh said. "Good afternoon to you."

She inclined her head. "Good afternoon, my lord," she said, expecting him to move on without further delay. She was surprised he had stopped at all.

He did not move on. He looked inquiringly at Amy.

"May I present my sister-in-law, Miss Easton, my lord?" she said. "The Marquess of Denbigh, Amy."

Amy smiled and curtsied as he made her a deeper bow than the one with which he had greeted Judith.

"I am pleased to make your acquaintance, my lord," Amy said.

"Likewise, ma'am," he said. "I did not know that your brother had any sisters."

"I have always lived in the country," Amy said. "But when Judith came to London and needed a companion, then I gladly agreed to accompany her. I have always wanted to see London."

"I hope you are having your wish granted, ma'am," he said. "You have visited the Tower and Westminster Abbey and St. Paul's? And the museum?"

"Westminster Abbey, yes," Amy said. "But we still have a great deal of exploring to do, don't we, Judith? We are going to drive down to the river tomorrow, or perhaps the day after since Judith is to attend a ball this evening and is likely to be late home. Have you heard that it is frozen over, my lord?"

"Indeed, yes," he said. "There is likely to be a fair in progress before the end of the week, or so I have heard."

"So it is not idle rumor," Amy said, smiling in satisfaction. "What do you think of that, Judith?"

Judith was not given a chance to express her opinion. The children had come running up, Kate to grasp her cloak and half hide behind the safety of its folds, Rupert to admire the marquess's horse.

"Will he kick if I pat his side, sir?" he asked. "He is a prime goer."

A prime goer! The phrase came straight from Maurice's vocabulary. It sounded strange coming from the mouth of a six-year-old child.

"Stand back, if you please, Rupert," she said firmly.

"He is a prime goer," the marquess agreed. "And I am afraid he is likely to kick, or at least to sidle restlessly away if you reach out to him in that timid manner and then snatch your hand away. You will convey your nervousness to him."

Rupert stepped back, snubbed.

"However, you may ride on his back, if you wish," the marquess said, "and show him that you are not at all afraid of him despite his great size."

Judith reached out a hand as Rupert's eyes grew as wide as saucers.

"Really, sir?" he asked. "Up in front of you?"

The marquess looked down at the boy without smiling so that Judith felt herself inhaling and reaching down a hand to cover Kate's head protectively.

"I don't believe a big boy like you need ride in front of anyone," Lord Denbigh said. And he swung down from the saddle, dwarfing them all in the progress. He looked rather like a rider from hell, Judith thought, with his black cloak swinging down over the tops of his boots, and his immense height.

"I can ride in the saddle?" Rupert gazed worshipfully up at the marquess. "Uncle Maurice says I am a half pint and must not ride anything larger than a pony until I am ten or eleven."

"Perhaps Uncle Maurice was thinking of your riding alone," the marquess said. "It would indeed not be advisable at your age to ride a spirited horse on your own. I shall assist you, sir."

And he stooped down, lifted the boy into the saddle, kept one arm at the back of the saddle to catch him if he should begin to slide off, and handed the boy the reins with the other.

"Just a short distance," he said, "if your mama has no objection."

Judith said nothing.

"Oh, how splendid," Amy said. "How kind of you, my lord. I am sure you have made a friend for life."

They did not go far, merely along the path for a short distance and back again. Judith stood very still and watched tensely. Her son's auburn curls-he was very like Andrew-glowed in marked contrast to the blackness of the man who walked at the side of the horse. She was terrified for some unaccountable reason. It was not for her son's safety. The horse was walking at a quite sedate pace, and the man's arm was ready to save the child from any fall.

She did not know what terrified her.

"There," the marquess said, lifting Rupert down to the ground again, "you will be a famous horseman when you grow up."

"Will I? Did you see, Mama?" Rupert screeched, his face alight with excitement and triumph. "I was riding him all alone.''

"Yes." Judith smiled at him. "You were very clever, Rupert."

"Do you think so?" he asked. "Will I be able to have a horse this summer, Mama, instead of a stupid pony? I will be almost seven by then. Will you tell Uncle Maurice?"

She cupped his face briefly with her hands and looked up to thank the marquess. And then she froze in horror as she saw him looking down at a tiny auburn-haired little figure who was tugging at his cloak.

"Me too," Kate was saying.

"No," Judith said sharply. And then, more calmly, "We have taken enough of his lordship's time, Kate. We must thank him and allow him to be on his way."

"Pegasus does not have a saddle for a lady," the marquess said. "But if you ask your mama and she says yes, I will take you up before me for a short distance."

"Please, Mama." Large brown eyes-also Andrew's- looked pleadingly up at her.

But was Kate not terrified of the man? Judith thought in wonder and panic. How could she bear the thought of being taken up before him on the great horse and led away from her mother and her aunt and brother? Kate was not normally the boldest of children.

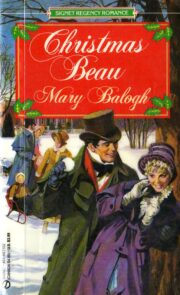

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.