"But you may go back to them?" he asked.

“I don't know,'' she said. ' T have made no definite plans for the future."

They were halfway along the driveway already. Soon they would be at the house. The next day his boys and he would be back at work again and unlikely to come near Denbigh Park. And she would have no further excuse to visit them. Time passed so quickly, she mought, and remembered a time not so long in the past when she had believed just the opposite.

"I wish…" he said, and stopped. "I wish you would meet some gentleman you could be fond of, Amy. Someone with a comfortable home and fortune. Someone with whom you could spend your remaining years in contentment."

Her throat ached as if she had just run for a mile without stopping. “I once dreamed of it," she said, “of a home and children of my own and a modest place in society. I no longer care much for the home and it is too late for the children. But I would still like to belong somewhere, to feel wanted and needed. To feel useful. But I count my blessings every day of my life."

"Ah," he said. "To feel useful. I can understand that need,

Amy. It is the way I felt before Max and I dreamed up our plan for our children's homes."

"Yes," she said, "and you found your dream. How I envy you."

They had reached the house. Rupert and Amy turned to look at them and Mr. Cornwell waved them on toward the doors.

"Run inside and get warm," he said.

"Will you come in and warm yourself before returning?" she asked.

"No." He patted her hand. "If I do that, Max will insist on calling out a sleigh or a carriage, as like as not and I will not get the exercise I need."

"Thank you for walking with me," she said as he took her hand in both of his and held it. “It has been a wonderful Christmas, has it not? The best I can ever remember."

"And for me too," he said, raising her hand to his lips. "You will be here for a few more days, Amy? Perhaps I will see you again before you leave. If I do not, have a safe journey home. I shall always hope that you find what you deserve in life. I'll never forget you."

She bit her lip. "Or I you," she said. Andinarush, "You are the first friend I have ever had outside the family."

"Am I?" He smiled at her. "Then I am deeply honored. And I shall hope always to be your friend. Perhaps if your sister-in-law and Max…"He smiled and shrugged. "Then perhaps we would meet again."

She nodded.

"Amy," he said softly, "it would not work. Believe me, it would not. You are a lady and brought up to the life of a lady."

An empty, empty, empty life, she thought, concentrating on their clasped hands. She nodded.

"I think maybe I should not come here in the next few days," he said.

She nodded again.

"Good-bye, then, my dear," he said after a pause. "For the first time in more than two years I wish things could be a little different, but they cannot."

She looked up into his face. "I wish it too," she said. "I wish other people did not always always know what is best for me. Is it my size, I wonder? Is it because I look so much like a child to be protected?" She withdrew her hand from his. "Good-bye, Spencer. Thank you for these few days. I cannot tell you all they have meant to me."

And she turned about and was gone up the steps and into the house before he could even return his arms to his sides. He stood for a long time frowning after her.

The Marquess of Denbigh was standing in the great hall when the two children came inside alone. He raised his eyebrows and looked at them.

“We just came home from the village,'' Rupert explained to him. "Aunt Amy is outside with Mr. Cornwell. Mr. and Mrs. Rundle came visiting and Mr. Rundle said he once met my papa. He said that papa liked to watch all the mills outside town, but Mrs. Rundle would not let him tell me about them. I think it was because ladies do not like to watch mills. Do they?"

"It is not considered a genteel sport for ladies," the marquess said, noticing that the little girl looked tired. She clung to her brother's hand and gazed upward at him with those dark eyes, which were going to fell a large number of young bucks when she was fifteen or sixteen years older. He smiled at her. "They do not derive much enjoyment from watching noses get bloodied. Don't ask me why."

The little girl had detached herself from her brother's side and was standing in front of the marquess, her arms raised. He picked her up and she set her arms about his neck and rested her cheek against his.

"Tired?" he asked.

She yawned loudly.

"Do you want me to carry you up to the nursery?" he asked.

She nodded. "Daniel lost his ball," she told him.

"Did he?"

"But he found it again."

"I am glad to hear that," he said.

"They all play cricket in the summer," Rupert said. He was trotting up the stairs at the marquess's side. "Cricket is a super game. I am going to play on the first eleven when I got to Eton, just like my papa did. Uncle Maurice told me."

"So did I," the marquess said, ruffling the boy's hair. "It is a noble ambition."

"Did you?" Rupert said, looking up at his host with renewed respect. "But I would like to play with the boys here. They all say that Joe is the best bowler. Perhaps if we come back in the summer I will be allowed to play with them. I will be almost seven by the summer."

The boy's hand was in his, Lord Denbigh noticed.

“I want to play with the dogs when we come back,'' Kate said.

The marquess allowed Rupert to open the nursery door since he did not have a free hand himself. Judith turned from the window at the far side of the room as they entered. She had obviously been awaiting the return of her children. Her face looked as if it had been carved out of marble.

“Mama.'' Her son raced toward her. "There was a gentleman at the house in the village who used to know Papa. He said I look just like him. He said he would have known me anywhere."

She rested a hand on his curls.

The marquess bent down to set Kate's feet on the floor. But she squeezed his neck tightly before scurrying across to her mother with some other pressing piece of news and kissed his cheek.

Judith was bending down to listen to her daughter's prattling as he turned to leave the room.

Christmas was not quite over, it seemed. The decorations still made the house look festive, and there were still all the rich foods of the season at dinner. And it appeared that the marquess's aunts had busied themselves during the afternoon organizing a concert for the evening.

''Everyone is to do something, Maxwell,'' Aunt Edith told him when they were all at table. “Miss Easton was not here, of course, when we made the plans. She was in the village with the dear children. But I am sure she will favor us with a selection on the pianoforte." She smiled at Amy. "And you and Mrs. Easton were out walking." Her smile, echoed by Aunt Frieda and Lady Tushingham, was almost a smirk.

“I shall read 'The Rape of the Lock,”' Lord Denbigh said. "It always shocks the ladies."

“But I am sure it cannot be quite improper despite its title if you are willing to read it aloud with ladies present, dear Maxwell," Aunt Frieda said.

Judith supposed she would sing. Amy would be willing to play for her. She had deliberately seated herself beside Mr. Rockford at dinner, knowing that a few carefully selected questions would keep him talking the whole time. She excused herself as soon as Lady Clancy got to her feet to signal the ladies to leave the gentlemen to their port, promising to return to the drawing room in time for the concert.

Kate and Rupert were both fast asleep, she found when she looked in at the nursery. She went to her own room. Her heart plummeted when there was a tap on the door almost immediately and Amy came inside. She so desperately wanted some time alone. But she needed to talk with her sister-in-law too.

"Amy," she said, "I have been meaning to tell you that we must…"

But Amy did not wait to hear what she had to say. "Judith," she said, her voice agitated, "is it possible that we can leave here tomorrow? Or that I can, perhaps? Is it possible that you can come with someone else later or else that you will not wish to leave at all?"

Judith had been wondering how her sister-in-law would react to having to leave Denbigh Park a few days earlier than they had planned. She frowned and watched aghast as Amy burst into tears and hurried across the room to gaze out of the window onto the dark world beyond.

"Amy?" she said. "What is it?"

"Oh, nothing." Amy blew her nose. "Just homesickness. This was not such a good idea after all, Judith. I have never been away from home at Christmas."

"Mr. Cornwell?" Judith asked softly.

Amy blew her nose again. "What a foolish, pathetic creature I am," she said. "I am thirty-six years old and from home for the first time in my life, and I fall stupidly in love with almost the first gentleman I meet."

"And he with you, if my eyes have not deceived me," Judith said. "He seems very fond of you, Amy. Did something happen this afternoon?"

"Only good-bye," Amy said. "And the assurance that 'it' would never work-whatever 'it' is. I am a lady, you see, and have been brought up to the life of a lady."

"Have you ever told him," Judith asked, "how lonely that life was, Amy, and how sheltered from the world you have always been? And have you ever told him how you surrounded yourself with the children and happiness whenever all your family came to visit?"

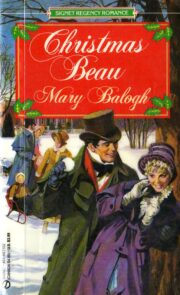

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.