"You must be longing for the sanity that the next few hours are going to restore to you, Max," Mr. Cornwell said, having abandoned his charges to the care of other willing adults for half an hour. He was sitting in his friend's library, one leg hooked casually over the arm of the chair on which he sat.

The marquess handed him a glass of brandy. "It will be quiet," he said. "My guests may find it unbearably so. The children have been general favorites, I believe."

Mr. Cornwell twirled the brandy in his glass and sipped on it. “We could not quite have foreseen all this two years ago, could we?" he said. "I must confess, Max, that I really did not expect to succeed. Did you?"

The marquess slumped into the chair opposite his friend's. "Yes," he said. "I expected that we would successfully set up homes, Spence. We were both too determined to allow the scheme to fail utterly, I think. What I did wonder about was whether the homes would become almost like other foundling homes with time-impersonal places where the children's basic physical needs would be cared for but nothing else. I wondered if the life would really suit you."

"I cannot imagine one that would suit me more," Mr. Cornwell said.

The marquess smiled. "You are like an experienced and indulgent father, Spence," he said. "You do not sometimes feel the need for a wife to make the illusion of family life more of a reality?"

His friend looked at him warily and lowered his glass. "Good Lord," he said. "What a strange question to ask, Max. I am almost forty years old."

The marquess shrugged. "I thought perhaps Miss Eas-ton…"he said.

Mr. Cornwell set his glass down and got to his feet. "Miss Easton is a lady, Max," he said.

"And you are a gentleman," Lord Denbigh said.

Mr. Cornwell scratched his head. "And father to ten lads who are anything but," he said. "Use your head, Max. I would not give up my boys, and even if I did, I would have almost nothing to offer a lady. It is true that I have enough blunt that you do not have to pay me a salary, but that is because my needs are modest. I would not drearn of inflicting my situation on Amy."

"A pity," the marquess said. "I like the lady."

"And so do I," Mr. Cornwell said fervently. "Good Lord, Max."

The marquess smiled. "Sit down and relax while you have the chance," he said. "And finish your brandy. She is going to walk back to the village with you after luncheon?"

"Violet and Lily have asked her," Mr. Cornwell said, "and half a dozen other children too. We are all going to have tea together at the girls' house to celebrate the success of the pageant."

"Ah," the marquess said, "then young Easton will want to go too."

Mr. Cornwell chuckled. "It is quite a challenge to have to find a wholly new part in a play at the very last moment," he said. "And I hated to have the boy be a shepherd and just stand about quite mute. I am afraid he almost stole the

scene. I fully expected our angel to tell him to pipe down when he was snoring so loudly. Yes, he will be coming to tea, of course."

"His sister will feel left out," the marquess said.

"Oh, she can come too," Mr. Cornwell said. "One extra child here or there really does not make much difference. And her aunt will be there to watch her. Young Daniel will be pleased. I think she reminds him of a little sister he left behind-which reminds me, Max. We might try to mount a search for her and include her with our next batch. Amy thinks it would be a good idea to have a home with boys and girls together and perhaps a married couple to care for them. What do you think?"

"An admirable idea," the marquess said, looking keenly at his friend.

The morning seemed interminable. He should not have risen so early, he supposed. But he had been unable to sleep. He had got up before dawn and taken blankets out to the gamekeeper's cottage in the woods, though there were bedcovers already there. And he had spent half an hour there gathering firewood, preparing a fire so that all that needed to be done was to light it.

He wondered if she would come with him there. He had made his intentions very clear to her the night before. He had left her in no doubt. He had seen the shock in her eyes, a virtuous lady being so openly propositioned by a gentleman who was not even her betrothed. But he had seen the desire too, the temptation, and the acceptance. And she had said yes.

That had been last night, of course. During the night and now in the cold light of day she might well have changed her mind. And she knew very well what was going to happen between them if she came with him.

He had wanted her to know that. He did not want either lier or his own conscience to be able to tell him afterward that it had been rape. She knew that if she came with him that afternoon he was going to take her. The only thing she did not know was his motive.

But then, did he?

She had her chance. Her chance to avoid his revenge despite the care with which he had set it up. He would get even with her if he could. But he could never force anything on her. He could not ravish her.

If she was the virtuous lady she appeared to be, he thought, watching the brandy swirling slowly in his glass, his jaw hardening, then she would find some excuse for not accompanying him that afternoon. She would save herself. And if she did so, if she refused to come, then he would let her go at the end of the week. Perhaps she would feel regret. Perhaps she already expected a declaration from him. Perhaps she would be disappointed-severely so maybe. It would be a sort of revenge. Not as satisfactory as he had originally planned, but good enough.

Truth to tell, he was becoming somewhat sickened by the whole thing. He wished her husband had not died or that he had never heard of it. He wished he had not heard that she was in London or that he had ignored the knowledge. He wished to God that he had never seen her again.

"Perhaps her mother will want to come with her," Mr. Corn well said.

The marquess looked up blankly. "Judith?" he said. "She has promised to come walking with me."

Mr. Cornwell raised his eyebrows and pursed his lips. "Has she, now?" he said. "In that case, Max, I shall have to assure the lady that the girls' house will be quite full enough with twenty-two children and three adults."

"Thank you," the marquess said. "I would appreciate that, Spence."

"I am not surprised, of course," Mr. Cornwell said. "It would have been pretty obvious to a blind man in the past couple of days. Your aunts have been nodding and looking very smug behind your back.''

Lord Denbigh got abrupdy to his feet and set his half-empty glass on the tray. He put the stopper back in the decanter. "It is not quite what you think, Spence," he said. "We had better go and see if any of my servants or dogs have been worried to death yet."

His friend chuckled and set an empty glass down beside his.

"You are quite sure you want to go?" Judith was stooped down tying the strings of Kate's hood beneath her chin.

Two large dark eyes looked back up at her and the child nodded.

"You want to be with the other children?" Judith smiled.

"Daniel is going to carry me on his shoulder," Kate said.

"You like Daniel?" Judith asked.

Kate nodded again.

"And you do not mind if Mama does not come with you?''

Kate put her arms about her mother's neck and kissed her cheek. "I'll tell you about it when I come home," she said.

"Well," Judith said, "Aunt Amy will be with you." She need not feel guilty, she thought, or as if she were neglecting her children. Rupert had already raced from the room and downstairs. And Mrs. Harrison, Mr. Cornwell, and Amy had all asked-separately-if Kate might be taken along too so that she would not be the only child left alone.

"Of course you must not feel obliged to come," Amy had said when Judith had expressed her concern. "Goodness, Judith, do you not believe that I will guard the children with my life? Besides…" she had added, but she had looked uncomfortable and had not finished the sentence.

Besides, she wished for some time alone with Mr. Corn-well? Amy had not been looking very happy all morning. Or rather, she had been looking too determinedly happy. Judith had seen her looking so once or twice when her father and her brothers had persuaded her to forgo some expected outing that might take her into too close a communication with strangers.

Had things not gone well for Amy at last night's ball? Judith wondered. Amy had been so very excited at the prospect of attending a ball. And she had danced several sets, two of them with Mr. Cornwell.

But there had been no announcement or private confidence during the evening-or this morning. Had Amy too been expecting, or hoping for, a declaration and not received it?

Kate reached up a hand to take hers and they left the nursery almost to collide with Amy, who was coming to meet them.

"Are you ready, Kate?" she asked. "Oh, and all nice and warmly dressed. Are you going to hold Aunt Amy's hand?"

"Ride on Daniel's shoulder," Kate said.

"Ah, of course," Amy said. "Daniel." She smiled brightly at Judith.

There was noisy chaos in the great hall. Mr. Rockford was solemnly shaking hands with all the children while the Misses Hannibal were kissing them. Two balls had escaped from their owners' hands. Someone was demanding to know what time it was since he had forgotten to wind his watch. A chorus of voices answered him. Mrs. Harrison and Mr. Cornwell were organizing the children into twos for the walk to the village. The marquess was standing cheerfully in the middle of it all.

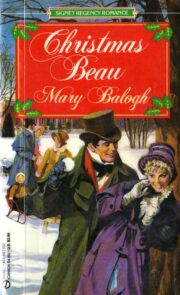

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.