"One thing I have learned about children in the past two years," he said. "They will respond to one word of praise faster than to ten of criticism. They need to feel good about themselves, as we all do. Good comes out of love and evil

out of hatred. And here I am mouthing platitudes. Come and dance with me."

She smiled and remembered the very stiff and formal and unsmiling gentleman to whom she had been betrothed for two months a long time ago. And the harsh, morose gentleman whom she had met again in London just a few weeks before. She looked up at the man who had just said with easy informality, "Come and dance with me."

It was a very intricate country dance, which she remembered only with difficulty and great concentration. Some people who attempted it did not know it at all. There was a great deal of laughter in the room as couples or individuals occasionally went spinning off in quite the wrong direction. Both the marquess and Judith were laughing as he spun her down the set after they had been separated for some of the patterns.

"There you are again at last," he said. "Did you promise to save a waltz for me, Judith? If not, promise now."

"I promise," she said, and they were separated again. She was dancing with a very large gentleman who was wheezing rather alarmingly from his exertions.

It was quite the most wonderful ball she had ever attended, she decided, looking about her at the twirling dancers and the berry-laden holly and up to the stars that twisted and glinted with the lights of dozens of candles above them in the chandeliers. By London standards it would not have been described as a great squeeze by any stretch of the imagination, but still to her it was wonderful beyond words.

She was back with Lord Denbigh again. "What a wonderful ball this is," she told him.

"You are not trying to flatter the host are you, Mrs. Easton?" he asked her.

"Yes, I am," she said. "I also mean it."

He smiled at her before they parted company yet again.

She would have been looking forward to their waltz with some impatience if she had not also wanted to live through and savor every moment of the evening.

"I have never seen them so excited or so puffed up with their own worth," Mr. Corn well said.

''They had every right to be," Mrs. Harrison said. “They did quite splendidly even if in the final performance they disregarded or forgot every suggestion we had made to them about their use of the English language. My only consolation is that half the audience probably had never even heard some of the words before. Perhaps they assumed they were Latin or Greek."

Amy laughed. “I could have hugged every one of them,'' she said.

"I believe you did," Mr. Comwell said.

The three of them were standing in the doorway of the ballroom, watching the vigorous country dance that had already been in progress by the time they arrived. Mrs. Harrison was being beckoned by the marquess's aunts and made her way to the empty chair beside them.

"Well, dear," Mr. Cornwell said, "Christmas is almost over."

Amy looked sharply up at him. "Yes," she said. "But it has been wonderful, and the glow of it will carry us all forward for some time to come."

"I sometimes worry about my boys," he said with a sigh. "And about the girls too. Shall we stroll? It seems that this set is not nearly finished yet." She set her arm through his and they began to stroll out into the great hall. "I worry about what will happen to them when we finally have to let them out into the world to fend for themselves."

"But you will not let that happen until they have been well prepared for some employment, will you?" she said. "And I believe that his lordship will help them find positions."

"Yes," he said. "But will they forget everything else they have learned? Love and sharing and respect and courtesy toward others and belief in themselves and everything else?''

Amy chuckled. "I do believe, Spencer," she said, "that you are sounding like any father anywhere. You are busy giving your charges wings but are afraid to let them fly. If they are loved, they will love. And they will carry with them everything else you have taught them and shown them and been to them."

everything else you have taught them and shown them and been to them."

He patted her hand. "You are a beautiful little person, Amy Easton," he said. "Where have you been hiding all my life?"

She laughed. “That is the first time I have ever been called beautiful," she said. "My family hid me at home. They were afraid I would be hurt if I went out into the world. They clipped my wings, you see."

"Was it smallpox?" he asked her.

She nodded. "Only me," she said. "It afflicted no one else in the family. For which I can only be thankful, of course."

"If they had only allowed you from home," he said, "you would have been called beautiful many times, Amy. Your beauty fairly bursts out from inside you."

"Oh," she said.

He worked his arm free of hers and set it about her shoulders. "And the exterior is not unpleasing either," he said. "Have you allowed a few pockmarks to influence your image of yourself?"

"Oh," she said, "I stopped even thinking about my:ppearance years ago. We have to accept ourselves as we are, do we not, or live with eternal misery."

"I wish…"he said, and stopped. He smiled at her. "I wish I had met you ten years ago, Amy, and had a fortune as large as Max's."

She swallowed. "I have never believed that wealth necessarily brings happiness," she told him. "And age makes no difference to anything." She looked up at him, liking and affection and hope in her eyes.

He stopped and drew her loosely into his arms. "Ah, Amy," he said, resting his cheek against the top of her head, “these are foolish ramblings. Forgive me. It has been a lovely Christmas, has it not?"

“Yes.'' There was an aching pain stabbing downward from her throat to her chest. And an inability to say more because she was a woman and because she had no experience whatsoever with such situations. "It has been the loveliest."

She drew her head back to smile at him and he lowered his to kiss her warmly on the lips.

"Come," he said, "I had better take you back to the ballroom while you still have some shreds of your reputation left. Will you dance the next set with me?"

"I have never danced in public," she said.

He frowned at her. "Clipped your wings?" he said. "Did they cut them off completely, Amy?"

She smiled.

"But in private?" he asked. "You danced in private?"

She nodded.

"Then we will see and hear no one else in the ballroom," he said. "You will dance for me-in private. Will you?"

"I would like to try," she said.

He drew her arm through his again and curled his fingers about her hand.

Chapter 13

His Aunt Frieda was flustered and tittering, protesting to Mr. Rockford that she had never seen the waltz performed and indeed had not even danced at an assembly for more years than she cared to remember.

Mr. Rockford was insistent and Aunt Edith nodding and simpering. Judith was close by and enjoying the moment.

"It is a very easy dance to learn, ma'am," she said. "All you have to do is move to counts of three and allow the gentleman to lead you."

Aunt Frieda threw up her hands, tittered again, and looked alarmed. The Marquess of Denbigh grinned as he walked up to the group.

"My dance, Judith?" he said, extending a hand to her. "Why do you not watch us for a minute, Aunt Freida?"

"Oh, yes," his aunt said gratefully as Judith placed a hand in his. "That would be best, Maxwell."

"And I am quite sure," Aunt Edith said, "that Maxwell and Mrs. Easton will waltz quite splendidly, Frieda, since they have both recently been in town and the waltz is all the crack there."

Judith was smiling up at him as he led her onto the floor and set one hand on her waist. "It was rather rash of Mr. Rockford to ask your aunt," she said. "She will probably have a fit of the vapors when she sees what a very improper dance it is."

"I believe my aunts are made of sterner stuff," he said. "And improper, Judith? Merely because one faces the same partner for the whole dance and can carry on a decent conversation?"

She continued to smile as the music began.

Both of his aunts were watching them intently. He was very aware of that and kept his steps simple. And he held her at arm's length, her spine arched back slightly from the waist, her hand light on his shoulder.

Improper? Hardly. There was distance between them. He touched her only at the waist, her other hand clasped in his. And yet there was something intimate about the waltz. There was something created within the circle of bodies and arms, some awareness, some tension. Not always, it was true. But with some partners. With Judith it was an intimate dance.

He kept his distance, kept his steps simple, kept conversing lightly with her. His aunts were still watching them, though Rockford was talking to Aunt Frieda and bowing.

It had been an intimate dance in London at the Mumford ball. Almost unbearably intimate. And tense. He had deliberately fostered the tension on that occasion, keeping his eyes fixed on her face the whole time, neglecting to converse with her. He had hated her at that time, Hatred and the desire for revenge had outweighed the renewed attraction he had felt toward her.

And now? But he did not want to spoil the evening or Christmas by thinking and analyzing.

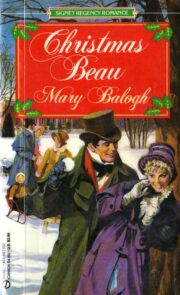

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.