She was not looking quite into his eyes, he saw, but at his chin, perhaps, or his neckcloth or his nose. But her chin was up, and there was that calmness about her. He had dreamed once of transforming that calmness into passion once

they were married. He had not known that behind it she was totally indifferent to him, perhaps even hostile.

It had been an arranged match, of course, favored by his father and her parents. He had been a viscount at the time. He had not succeeded to his father's title until three years before. But she had shown no open reluctance to his proposal. He had attributed her quietness to shyness. He had dreamed of awakening her to womanhood. He had dreamed of putting an end to his own loneliness, his own inability to relate to women, except those of the wrong class. He had loved her quite totally and quite unreasonably from the first moment he set eyes on her.

They had been betrothed for two months before she abandoned him, without any warning whatsoever and no explanation. They were to have been married one month later.

"Eight years, I believe," he said to her.

It was seven years and seven months, to be exact. She had been to the opera with him and two other couples. He had escorted her home, kissed her hand in the hallway of her father's house-he had never kissed more than her hand- and bidden her good night. That was the last he had seen of her until now.

"Yes," she said. "Almost."

"I must offer my belated condolences on your bereavement," he said.

"Thank you." She was twisting her glass around and around in her hands, the only sign that her calmness was something of a facade.

He made no attempt to continue the conversation. He wanted to see if there would be any other crack in her armor.

She continued to twist her glass, setting one palm against the base while she did so. She raised her eyes to his mouth, drew breath as if she would speak, but said nothing. She lifted her glass to her mouth to drink, though he did not believe her lips touched the liquid.

"Excuse me," she said finally. "Please excuse me."

It was only as his eyes followed her across the room that he realized that a great deal of attention was on them. She had probably realized it the whole time. That was good. He was not the least bit sorry. If she was embarrassed, good. It was a beginning.

He did not know quite when love had turned to hatred. Not for several months after her desertion, anyway. Disbelief had quickly turned to panic and a wild flight, first to the Lake District, and then to Scotland. Panic had turned to numbness, and numbness had finally given way to a deeply painful, almost debilitating heartbreak. For months he had dragged himself about on his walking tour, not wanting to get up in the mornings, not wanting to eat, not able to sleep, not wanting to live.

He had continued to get up in the mornings, he had continued to eat, he had slept when exhaustion claimed him. And eventually he had persuaded himself to go on living. He had done it by bringing himself deliberately to hate her, to hate her heartlessness and her contempt for honor and decency.

And yet hatred could be as destructive as heartbreak. He had found himself after his return to London hungry for news of her, going out of his way to acquire it-not easily done when she never came to town. He had found himself viciously satisfied when it became evident that Easton was returning to his old ways. She had preferred Easton to him. Let her live with the consequences.

Finally he had had to take himself off to his estate in the country to begin a wholly new life for himself, to try to stop the bitterness and the hatred from consuming him and destroying his soul.

He had succeeded to a large extent. He had focused the love she had spurned on other persons. And yet always there was the hunger for news of her. The birth of her children. The death of her husband. Her return to London.

And overpowering all his resolves, all his common sense, the need to see her again, to avenge himself on her, to even the score. He had been horrified at himself when he had heard of her arrival in London and had realized the violence of his suppressed feelings. Despite the meaningfulness, the contentment of his new life, they had been there the whole time, the old feelings, and they had proved quite irresistible. They had driven him back to London to see her again. The Marquess of Denbigh turned abruptly and left both the room and Lord Clancy's house.

Chapter 2

The weather was bitterly cold for December. Although there had been only a few flurries of snow, there had been heavy frost several mornings and some icy fog. And it was said that the River Thames was frozen over, though Judith had not driven that way to see for herself.

One was tempted to huddle indoors in such weather, staying as close to the fire and as far from the doors as possible. But Judith had lived in the country for most of her life and loved the outdoors. Besides, she had two young and energetic children who needed to be taken beyond the confines of the house at least once a day. It had become their habit to take a walk in Hyde Park each afternoon. Amy usually accompanied them there.

"One stiffens up quite painfully and feels altogether out of sorts when one stays by the fire for two days in a row," Amy said. "So exercise it must be. Old age is creeping up on me, Judith, I swear. Although sometimes I declare it is galloping, not creeping at all. I had to pull a white hair from its root just this morning."

Amy was a favorite with Kate because she was always willing to listen gravely and attentively to the child's often incomprehensible prattling. She had always seemed to know what Kate was talking about, even in those earlier days when no one but Amy-and Judith, of course-had even believed that the child was talking English.

"I just wish," Judith said, her hands thrust deep inside a fur muff as they walked along one of the paths in the park two days after Lady Clancy's soiree, "that taking one's exercise was not so utterly uncomfortable sometimes. I would be convinced that I had dropped my nose somewhere along the way if I could not see it when I cross my eyes. It must be poppy red."

"To match your cheeks," Amy said. "You look quite as pretty as ever, Judith, have no fear."

"I just hope I will not have to appear at the Mumford ball tonight with ruddy cheeks and nose," Judith said. "Indeed, I wish I did not have to appear there at all. Or I wish you would come too, Amy. Won't you?"

"Me?" Amy laughed. "Maurice once told me that I would be an embarrassment to gentlemen at a ball since I scarce reach above the waist of even the shortest of them. Henry agreed with him and so did Andrew. They made altogether too merry with the idea, but they were quite right. Besides, I am far too old to attend a ball in any function other than as a chaperone. And since you do not need a chaperone, Judith, I shall remain at home."

Judith felt her jaw tightening with anger. How could Amy have remained so cheerful all her life, considering the treatment she had always received from her family? They were ashamed of her, embarrassed by her. They had always liked to keep her at home, away from company, where she would not be seen.

Judith had tackled Andrew about it on one occasion, before she had learned that he did not have a heart at all. She had accused him and his brothers of cruelty for persuading Amy against attending a summer fair in a neighboring town.

"We have her best interests at heart," he had said. "We don't want her hurt, Jude. She might as well stay with the family, where her appearance does not make any difference."

"Perhaps one day," she said now, "we can drive down to the river to see if it is true about the ice. Claude says that if it thickens any further there will be tents and booths set up right on the river and a frost fair. But I am sure he exaggerates."

"But how exciting it would be," Amy said. "Booths? To sell things, do you think, Judith? But of course they would if it is to be likened to a fair. Perhaps we can buy some Christmas gifts there. I have not bought any yet, and there are only three weeks to go."

Amy entered into the excitement of the prospect and pushed

from her mind the mention of the ball. Balls were not for her. It was too late for her. There had been a time when she had dreamed of London and the Season and a come-out. It was true that her glass had always told her that she was small and plain, and of course she had those unfortunate pockmarks on her forehead and chin. But she had been a girl and she had dreamed.

Her father had never taken her to London. And finally it had dawned on her that he considered her unmarriageable. She had gradually accepted reality herself. She was an old maid and must remain so. She learned to take pleasure from other people's happiness and to love other people's children.

"Run along, by all means," she said when Kate tugged at her hand. "Aunt Amy is quite incapable of breaking into a run." She released her niece's hand and watched her race forward to join Rupert.

Judith watched the two children ahead of them. Rupert was a ship in full sail and was weaving and dipping about an imaginary ocean. Kate was hopping on first one leg and then the other.

It was hard to believe that Christmas was approaching. There was no feel of it, no atmosphere to herald the season. Christmas had always been a well-ceiebrated occasion in her family, and for a moment she regretted having decided against the long journey to Scotland and her sister's family. It would have been good once they had arrived there.

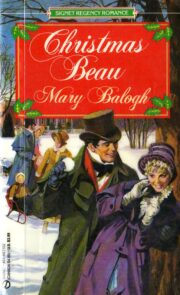

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.