"Amy," he said, smiling. "A little name for a little lady. You live all the time with Mrs. Easton?"

Yes, Amy thought, as Peg ran up beside her and took her hand, my cup runneth over.

It was almost ten o'clock when the carolers finally arrived at Denbigh Park, bringing a draft of cold air with them through the front doors and a great deal of noise and merriment. Cheeks and noses were red and eyes were shining. Stomachs were full. Five of the smallest children clutched the lanterns and hoisted them high when it came time to sing, though they were largely for effect; the hall was well lit. The smallest child of all was asleep against Mr. Cornwell's shoulder.

The marquess and his guests came down from the drawing room to listen to the carols, quite content to have their own singsong to Miss Frieda Hannibal's accompaniment interrupted. Kate, her cheeks bright with color, her eyes wide with the lateness of the hour, clung to Judith's neck and waved across a sea of heads at Daniel.

Mr. Cornwell had a hand on Amy's shoulder and watched the music she held in her hands.

The carolers made up in volume and enthusiasm what they lacked in musical talent, Judith thought after they had sung "Hark the Herald Angels Sing" as if they were summoning all listeners to the nearest tavern and "Lully Lulla Thou Little Tiny Child" as if they intended their rendition to be heard in Bethlehem.

It did not matter that the choir was unskilled. It did not matter at all. For there they all were, crowded into the great hall of Denbigh Park, a roaring log fire burning at either side of it, sharing with one another and their listeners all the joy of Christmas.

There was nothing quite like the magic of those few days, Judith thought. And every year it was the same. Even during those years with Andrew's family, though she had not enjoyed them on the whole, there had always been some of the magic.

Or perhaps magic was the wrong word. Holiness was perhaps a better one. Love. Joy. Well-being. Goodwill. All the old cliches. Cliches did not matter at Christmastime. They were simply true.

Everyone was smiling. Mr. Rockford, whose conversation was never of the most interesting because he did not know when to stop once he had started, had one of the marquess's aunts on each arm and was beaming goodwill as were they. Sir William and Lady Tushingham, who had regaled them at dinner with stories of their nephews' and nieces' accomplishments and triumphs, were flanked by Lord and Lady Clancy and looked rather as if diey were about to burst with geniality.

The Marquess of Denbigh was standing with folded arms, his feet set apart, smiling benignly at all the children. Just a week before, Judim thought, she would not have thought him capable of such an expression.

And Amy was smiling up over her shoulder at Mr. Corn-well, the singing at an end and the hubbub of excited children's voices being in the process of building to a new crescendo. And he was pointing upward to a limp spray of mistletoe that some wag had suspended from the gallery above and lowering his head to give her a smacking kiss on the lips.

Judith, watching his beaming face and Amy's glowing expression, felt as if warmth was creeping upward from her toes to envelope her. If anyone on this earth deserved happiness, she thought, it was Amy. And there would be nothing at all wrong with that match. Nothing.

"Mama!" Rupert was patting her leg and talking quite as loudly and excitedly as any of the children. "Did you hear me? I got to carry the lantern for part of the way. And I am going to walk to church with Ben and Stephen. They said I may."

" 'Ow's my nipper?" Daniel was demanding loudly, and Kate wriggled to be set down from her mother's arms.

There were more refreshments and a great deal more noise in the half hour that remained before it was time to go to church. The marquess's aunts and Sir William and Lady Tushingham would ride to church in the sleighs, it had been decided. Lord and Lady Clancy would walk, though the marquess offered to have one of the sleighs return for a second trip.

Three of the smaller children, including Henry, gave in to the lateness of the hour and the long excitement of the day and the novelty of having the big house to sleep in and agreed to stay with Mrs. Webber and be put to bed. Kate, after several huge yawns, was persuaded to stay with them.

And so they set out into the crisp night air, the distant sound of the church bells ringing out their glad tidings of the birth of a baby in Bethlehem and the coming into the world of a savior.

"It is so easy to forget," Judith said, finding herself walking beside the marquess and taking his offered arm. "There is so much to do and so much to enjoy that sometimes we forget what the season is all about."

"Yes," he said. "Going to church on Christmas Eve is rather like walking into the peace at the heart of it all, is

it not? But we will be reminded again tomorrow. The children will be performing their pageant between dinner and the start of the ball."

"Yes," she said, smiling.

She liked him. She admitted the amazing truth to herself at last-not only that she liked him but that he was a likable person. And she wondered if he had always been so or if he had changed in eight years. If he had always been like this, she thought, then…

She stopped her thoughts. She did not want to be sad on Christmas Eve. She did not want to look back in regret on all that she might have missed. Besides, there were Rupert and Kate. Her years wim Andrew had not been all bad. She had not wasted those years of her life. There were her children.

The sounds of the church bells pealing out their invitation grew louder as they stepped onto the village street. People were flocking to church, many of them on foot, some by sleigh.

The Marquess of Denbigh smiled to himself. The singing at the village church was not usually noted for its volume or enthusiasm. And yet tonight, with the familiar Christmas hymns, the whole congregation seemed infected by the spirited singing of the children. And the rector, no longer rendering a virtual solo, as he was usually forced to do, lifted up his rich baritone voice and led his people in welcoming a newborn child into the world once more.

There was no time like Christmas, the marquess thought, to make one feel at peace with the world. He could not for the moment think of one enemy whom he could not forgive or one enmity that was worth holding onto. The one spot of darkness on his soul he pushed from his mind. It was unbecoming to the occasion. And he was filled with that unrealistic dream that infects all of the Christian world at that particular season of the year that love was enough, that all the problems of the world and of humanity would be solved if only the spirit of Christmas could persist throughout the year.

He smiled inwardly again. He knew that it was a foolish dream, but he allowed himself to be borne along by it nevertheless.

Judith shared his pew to the right, his aunts and Rockford to his left. His other guests sat in the pew behind, the children behind them again. His neighbors packed the rest of the church. It was a good feeling of well-being. He turned his eyes to the right as the congregation sat for the sermon and watched Judith clasp her hands loosely in her lap.

And he indulged in his other dream for a moment before turning his attention to what the rector was saying. She was his wife and had been for several years. Their children were at home in the nursery or sitting behind them with the other children. They were celebrating Christmas together.

He knew that there was something about her, about his relationship to her and his plans for her, that he needed to think through. There were perhaps some adjustments to make in light of new evidence. But not at present. Later he would think.

Judith, sitting beside him, was trying to remember a Christmas when she had felt happier. There had been the Christmases of her childhood and girlhood, of course. They had always been happy times. But since then? Surely the first year or two after her marriage had brought pleasant Christmases. Certainly Ammanlea had always been full of family members and children. There had been all the ingredients for joy.

But she remembered that first Christmas, when she had still been in love with Andrew. He and his brothers and male cousins had spent the afternoon and evening of Christmas Eve going from house to house wassailing and using the occasion as an excuse to get themselves thoroughly foxed. Andrew had fallen asleep several times during church while she had prodded him with her elbow with increasing embarrassment. And all the next day at home they had continued to drink.

And that had been the pattern for all the Christmases of her marriage and for the first of her widowhood.

It was little wonder, she thought, that she was feeling so

happy this year. So unexpectedly happy. She had been horrified when Lord Denbigh had trapped her into coming to Denbigh Park. She had still been convinced that he was a harsh and unfeeling man and that he had issued the invitation only to punish her for humiliating him eight years before.

She had never dreamed that she could come to like him, and more than that, to admire him. She had never dreamed that she would stop fighting the strong physical attraction she felt for him.

She had stopped fighting, she realized. She had stopped that afternoon, if not before. She could still feel the warmth of his hand on hers beneath her muff-the hand that was now spread on one of his thighs. She glanced at it. It was a slim, long-fingered hand, which nevertheless looked strong.

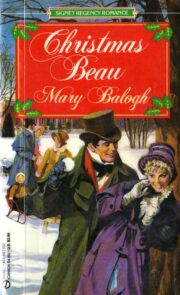

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.