"Time up!" the marquess yelled when the five minutes were over, and the air rained snowballs. There were squeals and yells and bellows and giggles, and sure enough, his girls had the early advantage as the boys abandoned their fortifications and were forced to make their weapons while defending themselves against continuous attack.

Miss Easton, he saw, flanked by two of the larger boys, who were certainly as large as she, was engaged in a duel with Spence. Mrs. Harrison was defending herself against attack from a group of her girls. Rockford, laughing and clearly enjoying himself, was allowing a group of little boys, including Rupert, to score unanswered hits on his person.

And then a large snowball shattered directly against the marquess's face.

"Oh, no," Judith Easton yelled as his eyes locked on her. She was laughing helplessly. "I have lamentably poor aim. I was throwing at that little boy who just hit me." She pointed at Trevor.

He bent and scooped up a large handful of snow, not taking his eyes from her despite the fact that two more snowballs hit him, one on the shoulder and one on the knee. He molded his snowball very deliberately.

"You would not," she called to him as he strode toward her, and she stooped down to scoop snow harmlessly in his direction and then turned to dart behind the snow hills thrown up by her boys.

He followed her there. She was still laughing. And looking damned beautiful, he thought. He would not allow himself for the moment to think anything else. He was enjoying himself.

"Don't, please," she said, setting her hands palm out in front of her. She could not stop laughing. "Please don't."

He reached out with one booted foot, caught her smartly behind the ankles, jerked forward, and sent her sprawling back into the snow bank. Beyond the bank there was a great deal of noise and a great barrage of snowballs still flying in both directions.

"How clumsy of you," he said, stretching down his free hand for one of hers. "Do allow me to help you up, ma'am.''

"Oh, most unfair," she said. "I am going to be caked with snow."

"In future," he said, drawing her to her feet when she set her hand in his, "you must be careful about allowing your feet to skid on the snow." He drew her all the way against him and held her there with one arm about her. "You could easily break a leg, you know."

The laughter was dying from her face, only inches from his. A great awareness was taking its place in her eyes. He could feel his heart beating in his throat and in his ears. He moved his head an inch closer to hers, his eyes straying down to her mouth. Her lips were parted, he saw.

The temptation was great. Almost overpowering. One taste while everyone's attention was distracted and they were partially shielded anyway by the snow bank. One taste, though it was far too early for such familiarity. But he had a plan to follow. A plan that called for greater patience and caution.

"Revenge can be very sweet sometimes," he told her in a low voice, keeping his eyes on her mouth as he brought

his hand from behind her and pressed his snowball very firmly against her face.

"Argh!" she said, sputtering snow.

He laughed and turned away. "Time up!" he yelled. "I have penetrated the enemy defenses, as you can all see, and declare the men and girls to be the winners."

Shrieks of delight from the girls and high-pitched insults hurled at the boys in place of snow. Loud protests and bloodcurdling threats from the boys.

"Back to the house," the marquess said. "If we cannot have luncheon and rehearse for the Christmas pageant soon enough, there will be no time for skating on the lake afterward."

Skating! The word was like a magic wand to set everyone scurrying in the direction of home. Most of the children had skated the year before during a cold spell and remembered their bruises and their triumphs with an eagerness to have them renewed.

"I can skate like the wind," Rupert Easton told the marquess, falling into step beside him and reaching up a hand to be held, forgetting for the moment that he was six years old and a big boy.

"Then I will have to see proof this afternoon," Lord Denbigh said, taking the hand in his. Judith, he could see, was walking with Rockford. He, inevitably, was doing all the talking.

The marquess was still regretting that he had not after all kissed her before making use of his snowball.

Chapter 8

Gathering the Christmas greenery had not taken as long as expected. There was still time when they returned to the house to decorate the drawing room and the ballroom, though the marquess did suggest that perhaps the children would welcome a rest before beginning work again.

"Of course," he added to Mr. Cornwell, who was taking a bundle of holly very carefully from Amy's arms, "I might have saved my breath as you obviously have not taught the meaning of the word rest in that school of yours yet, Spence. What do you teach, anyway?"

Judith hoped fervently that the outing would have tired Kate even if not Rupert. She hoped that at least her daughter would be willing to be taken back to the nursery. But Kate had attached herself to Daniel, and Daniel had promised that he would lift her onto his shoulders so that she could hang some of the greenery over the mantel and perhaps over some of the pictures.

"Though I think you'd 'ave to sprout arms ten feet long to reach the pictures, nipper," he added. "P'raps I'll stand on a chair."

Judith closed her eyes briefly.

She longed to escape, but there was no excuse to do so. Lord and Lady Clancy and Sir William and Lady Tushingham had also appeared to help, and even the marquess's aunts had come downstairs from their rooms to exclaim at the enormous piles of holly and mistletoe and pine boughs and at the size of the Yule log.

Mr. Cornwell, Amy, Mr. Rockford, and the Tushinghams would help supervise the decorating of the drawing room, it was decided. The rest of the adults would move on to the ballroom.

She longed to escape, Judith thought, and yet there was that old seductive excitement about the sights and smells of Christmas in the house. The smell of the pine boughs was already teasing her nostrils. At Ammanlea the servants had always done the decorating. At her home they had always done it themselves. It was good to be back to those days, and good to see so many children happy and excited and working with a will.

She shook off the mental image of Daniel standing on a delicate chair in the drawing room with Kate on his shoulders reaching up to a picture. One of the adults would doubtless see to it that no unnecessary risks were taken.

Several large boxes had been set in the middle of the ballroom and soon the children were into them, unpacking bells and ribbons and bows and stars-several large, shining stars.

"To hang from the chandeliers," the marquess explained. "No, Toby, it would be far too dangerous. I would hate to see you with a broken head for Christmas. I shall do it myself."

And Judith, gingerly separating piles of holly into individual sprigs so that the children could rush about the room placing them in suitable and unsuitable spots, also watched the marquess remove his coat and roll up his shirt sleeves to the elbows. She watched him climb a tall ladder held by Lord Clancy and two of the biggest boys in order to attach the stars to the chandeliers.

She held her breath.

And then looked away sharply to resume her task and suck briefly on one pricked finger. She did not want this to be happening, she thought fiercely. She did not want this feeling of Christmas, this growing feeling of warmth and elation, to be associated in any way with him.

But how could she help herself? Ever since her arrival the afternoon before, and especially this morning, she had been fighting the realization that perhaps he was not at all as she had always thought him to be. She remembered her impressions of him eight years before, impressions gathered over a two-month period. He had seemed cold, morose, harsh, silent. She had been afraid of him. And there had been

nothing in London this time to change that impression.

Oh, there had been, of course. There had been his civility to Amy, his kindness to her children and even to her. But her fear of him had not lessened. She had suspected his motives, had assumed that somehow it was all being done to punish her, since he knew that the worst he could do to her was inflict his company on her and ingratiate himself with her family.

But here? Could she really cling to her old impressions here? He was mingling with twenty children from the lowest classes, teasing them, playing with them, making them as happy as any children anywhere at Christmas time. And it could not even be said that it was just a financial commitment to him, that he provided the money while Mr. Cornwell and Mrs. Harrison did all the work and all the caring. That would not be true. He so clearly loved all the children and enjoyed spending time with them.

She recalled the contempt she had felt for him in London when he had remarked on one occasion that he had a fondness for children. He had not lied-that was becoming increasingly obvious. Rupert had tripped along at his side all the way back to the house, his hand in the marquess's, talking without ceasing.

"There," she said to Violet, smiling, "that is the last of it."

Mrs. Harrison and two of the girls were just coming in with armloads of ivy, she saw.

She did not want this to be happening. Lord Denbigh, still in his shirt sleeves, was standing in the middle of the ballroom, his hand on Benjamin's shoulder, pointing across the room at something. Ben went racing away.

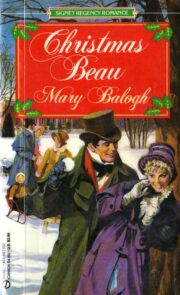

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.