He rested his head back against the cushions of his carriage and closed his eyes. Not yet, my lady. Not quite yet.

But did he want her to suffer as he had suffered? He thought back to the pain, dulled by time but still bad enough to make his spirits plummet.

Yes, he did want it. She deserved it. She should be made to know what her selfish and careless rejection had done to another human heart. She deserved to suffer. He wanted to see her suffer.

He wanted to break her heart as she had broken his.

He opened his eyes. Except mat his hatred, his plans for revenge, seemed unreal in this setting. He had found happiness here in the past few years-or near happiness, anyway. And he had found it from companionship and friendship and love-and from giving. He had found peace here if not happiness.

Would he be happy after he had completed his revenge on Judith Easton?

He closed his eyes again and saw her as she had been eight years before: shy, wide-eyed, an alluring girl, someone with whom he had tumbled headlong in love from the first moment of meeting. Someone whom he had been so anxious to please and impress that he had found it even more impossible than usual to relax and converse easily with her. Someone who had set his heart on fire and his dreams in flight.

And he remembered again that visit from her father putting an end to it all. Just the memory made the bottom fall out of his stomach again.

Yes, he would be happy. Or satisfied, at least. Justice would have been done.

Kate was asleep on Amy's lap, a fistful of Amy's cloak clutched in one hand. Rupert should have been asleep but was not. He was fretful and had jumped to the window twenty times within the past hour demanding to know when they would be there.

Judith did not know when they would be there. She had never been either to Denbigh Park or to that part of the country before. All she knew was that it would be an

enormous relief to be at the end of the journey but that she wished she could be anywhere on earth but where she was going.

Her anger had not abated since the afternoon during which she had been trapped into accepting this invitation. But she had been forced to keep it within herself. Amy was quite delighted by the prospect of spending Christmas in the country after all, part of a large group of people. And the children were wildly excited. Judith had voiced no objections, realizing how selfish she had been to have decided against spending the holiday with Andrew's family that year.

Amy of course was delighted not only by the invitation but also by what she considered the motive behind it.

"Can you truly say," she had asked after the marquess had left the house, "that you no longer believe he has a tendre for you, Judith? Do you still refuse to recognize that he is trying to fix his interest with you?"

"I do not know why he has asked us," Judith had said, "but certainly not for that reason, Amy."

Her sister-in-law had clucked her tongue.

But Judith had lain awake for a long time that night. He had said that he had waited eight years for a second chance with her. He had called her by her given name. He had kissed her hand, something he had done several times during their betrothal.

She could not believe him. She would not believe him. And yet her breath had caught in her throat at the sound of her name on his lips and she had felt the old churning of revulsion in her stomach when he had kissed her hand.

Except that it was not revulsion. She had been very young and inexperienced when they were betrothed. She had called it revulsion then-that breathless awareness, that urge to run and run in order to find air to breathe, that terror of something she had not understood.

She had called it revulsion now too for a couple of weeks, from mere force of habit. But it was not that. She had recognized it for what it was at me foot of the stairs when he had kissed her hand. And the realization of the truth terrified her far more than the revulsion ever had.

It was a raw sexual awareness of him that she felt. A sort of horrified attraction. A purely physical thing, for she did not like him at all-and that was a gross understatement. She disliked him and was convinced, despite his words and actions, that he disliked her too. She distrusted him.

And yet she wanted him in a way she had never wanted any man, or expected to do. She wanted him in a way she had never wanted Andrew, even during those weeks when she had been falling in love with him and contemplating breaking a formally contracted betrothal. In a way she had never wanted him even after their marriage during that first year when she had been in love-the only good year.

And so if the Marquess of Denbigh was trying to punish her-and it had to be that-then he was succeeding. She was a puppet to his puppeteer. For the wanting him brought with it no pleasure, no longing to be in his company, but only a distress and a horror. Almost a fear.

Amy closed her arm more tightly about Kate and reached up for the strap by her shoulder. Rupert let out a whoop and bounced in his seat. The carriage was turning from the roadway onto a driveway and stopping outside a solid square lodge house for directions. But the coachman's guess appeared to have been right. The carriage continued on its way along a dark, tree-lined driveway that seemed to go on forever.

"Oh," Amy said, peering from her window eventually. "How very splendid indeed. This is no manor, Judith. This is a mansion. But then I suppose we might have expected it of a marquess. And then, Denbigh Park is always mentioned whenever the great showpieces of England are listed. Is that a temple among the trees? It looks ruined."

"I daresay it is a folly," Judith said.

The house-the mansion-must have been built within the past century, she thought. Or rebuilt, perhaps. It was a classical structure of perfect symmetry, built of gray stone. Even the gardens and grounds must be of recent design. There were no formal gardens, no parterres, but only rolling lawns and shrubberies, showing by their apparent artlessness the hand of a master landscaper.

Their approach had been noted. The front doors opened as the carriage rumbled over the cobbles before them, and two footmen ran down the steps. The marquess himself stood for a moment at the top of the steps and then descended them.

And if she had had any doubt, Judith thought, tying the ribbons of her bonnet beneath her chin and drawing on her gloves and cautioning Rupert to stay back from the door, then surely she must have realized the truth at this very moment. Something inside her-her heart, her stomach, perhaps both-turned completely over, leaving her breathless and discomposed.

And angry. Very angry. With both him and herself. He looked as if he had just stepped out of his tailor's shop on Bond Street, and there was that dark hair, those harsh features, those thin lips, the piercing eyes and indolent eyelids. And she was feeling travel-weary and rumpled. She was feeling at a decided disadvantage.

The carriage door was opened and the steps set down and the marquess stepped forward. Rupert launched himself into his arms-just as if he were a long-lost uncle, Judith thought-and launched into speech too. The marquess set the boy's feet down on the ground, rumpled his hair, and told him to hurry inside where it was warm. And he reached up a hand to help Judith down.

"Ma'am?" he said. "Welcome to Denbigh Park. I hope your journey has not been too chill a one."

She was more travel-weary than she thought, she realized in utter dismay and mortification a moment later. She stepped on the hem of her cloak as she descended the steps so mat she fell heavily and clumsily into his hastily outstretched arms.

A footman made a choking sound and turned quickly away to lift down some baggage.

"I do beg your pardon," Judith said. "How very clumsy of me." There was probably not one square inch on her body that was not poppy red, or that was not tingling with awareness, she thought, pushing away from his strongly muscled chest.

"No harm done," he said quietly, "except perhaps to your pride. Is the little one sleeping?" He turned tactfully away to look up at Amy, who was still inside the carriage. "Hand her down to me, ma'am, if you will."

Judith watched as he took Kate into his arms and looked down at her. The child was fussing, half asleep, half awake.

"Sleeping Beauty," the marquess said, "there will be warm milk waiting for you in the nursery upstairs, not to mention a roaring fire and a rocking horse. But I daresay you are not interested."

Kate opened her eyes and stared blankly at him for a few moments. Then she smiled slowly and broadly up at him while Judith felt her teeth clamping together. A long-lost uncle again. How did he do it?

"Do let me take her, my lord," she said, and felt his eyes steady on her as she relieved him of his burden.

He turned to help Amy down to the cobbles.

"What a very splendid home you have, my lord," Amy said. "It has taken our breath quite away, has it not, Judith? Are we not all fortunate that there has been no more snow in the past week? Though of course it is cold enough to keep the ice on the lakes and rivers. I do declare, it must be the coldest winter in living memory. And it is only December yet."

"I have snow on order for tomorrow or Christmas Eve," Lord Denbigh said. "And plenty of it too. It cannot fail, ma'am, now that all my guests have arrived. And it has been trying so hard for the past two weeks or more that it surely will succeed soon."

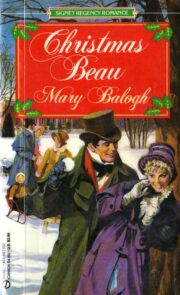

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.