"Skating," Rupert said, longing in his voice. "I can skate like the wind. Papa said so when we used to skate before he died."

Kate was patting the marquess's waistcoat with her free hand. He looked down at her.

"Yes, ma'am?" he said. "What may I do for you?"

"Can we come?"

"Kate!" Judith's cup clattered back into her saucer.

"Actually," he said, "my very reason for coming here today was to invite you. Would you like to come?" He looked from Kate to Rupert.

Rupert jumped to his feet. "Mama too?" he yelled.

"Aunt Amy too?" Kate asked.

"All of you," he said. "I cannot quite imagine Christmas without you. Will you do me the honor of coming, ma'am?" He looked directly at Amy. "Despite the shortness of the notice?"

"Oh." Amy clasped her hands to her bosom and looked across at Judith.

"Ye-e-es!" Rupert cried.

Kate looked fixedly up into the marquess's face.

"Ma'am?" Lord Denbigh looked at Judith, whose face had lost all color. "Perhaps I should have asked you privately? It looks as if your family will be disappointed if you say no and you would, very unfairly, seem to be the villain. But it will please me more than I can say if you accept."

"Oh, Judith," Amy said, "it would be so wonderful."

"Lord Denbigh's housekeeper will not be expecting four extra guests," Judith said in a strangled voice.

"My housekeeper is always ready for guests," the marquess said. "She has learned from experience that they may descend upon her at any time and in any numbers."

"But it must be your decision," Amy said. "I told you when I came to live with you, Judith, that I would go wherever you wished to go and do whatever you wished to do. I meant it."

Judith turned her eyes from the marquess's to look first at her sister-in-law's resigned expression and then at her son's tensely excited one. And at Kate, who was looking at her with wide, solemn eyes.

"Please, Mama?" Rupert said.

"It is extremely kind of you to invite us, my lord," she said. "We accept."

There was great jubilation in the room while she held the marquess's eyes for longer than necessary. Yes, my lady, he told her silently. Now do you begin to understand?

When he rose to take his leave five minutes later, she rose too and accompanied him from the room and down the stairs.

"Why?" she asked him quietly as they descended the stairs side by side. "Have you not punished me enough?"

"Punished?" He looked at her, eyebrows raised.

"You know what I mean," she said. "Please do not pretend innocence. You have stalked me ever since that evening in Lady Clancy's drawing room. You have done all in your power to make me uncomfortable, to make me the topic of gossip and speculation. And you have used my children against me. Today more than ever. Yes, of course you should have spoken with me about this invitation first. But you knew very well what your answer would have been. When is this punishment to end?"

He stopped at the bottom of the stairs and turned to frown down at her. "Punishment?" he said. "Is that how you see my attentions, Judith? Is that how you always saw them? I have used your children, yes, and your sister-in-law. That is somewhat dishonorable, I will confess. But I will use all the means at my disposal. I have waited almost eight years for my second chance with you. I do not wish to squander it as I did the first."

He held her amazed eyes with his own as he took her nerveless hand from her side and raised it to his lips.

She was still standing at the foot of the stairs after he had donned his greatcoat and gathered up his hat and gloves. He looked at her once more before nodding to her father's butler to open the outer door for him.

And he stood for a moment on the steps outside, smiling grimly to himself.

Chapter 6

The Marquess of Denbigh left town two days later. Fortunately, the snow had done no more than powder the fields and the hedgerows beside the highways. And the weather remained too cold, some said, for there to be danger of much snow.

His guests were not due to arrive until three days before Christmas, but there was much he wished to do before then. He must make sure that invitations were sent out for the ball on Christmas Day. His neighbors would be expecting them, of course, since he had made it a regular occurrence since his assumption of the title. But still, the formalities must be observed.

And then he must make sure that all satisfactory arrangements had been made for the children. Ever since bringing them to the village of Denbigh two years before, he had tried to make Christmas special for them-having them to stay at the house for two nights, providing a variety of activities for their entertainment, filling them with good foods, encouraging them to contribute to the life of the neighborhood by forming a caroling party, making sure that they felt wanted and loved.

This year Cornwell and Mrs. Harrison had reported that the children were preparing a Christmas pageant. He would have to decide when would be the best time for its performance. The evening of Christmas Eve would seem to be the most suitable time, but that would interfere with the caroling and the church service.

Perhaps the afternoon? he thought. Or the evening before? Or Christmas Day?

He ran through his guest list in his mind. Sir William and Lady Tushingham would be there. They were a childless couple of late middle years, who boasted constantly and tediously about their numerous nephews and nieces but who seemed always to be excluded from invitations at Christmas. And Rockford, who was known-and avoided-at White's as a bore with his lengthy stories that were of no interest to anyone but himself, and who had as few family members as he had friends. Nora and Clement had agreed to come this year as their only daughter was spending the holiday with her husband's family. And his elderly aunts, Aunt Edith and Aunt Frieda, who had never refused an invitation to Denbigh Park since the death of his father, their brother, from whom they had been estranged.

And the Eastons, of course. He wondered how high in the instep Judith Easton was and how well it would please her when she discovered who all the children he had spoken of were. He wondered if she would approve of her son and daughter mingling with the riffraff of the London slums. He smiled grimly at the thought.

He had brought them to Denbigh a little more than two years before after sharing several bottles of port with his friend Spencer Cornwell one evening. Spence was impoverished, though of good family, and restless and disillusioned with life. He was a man with a social conscience and a longing to reform the world and the knowledge and experience to know that there was nothing one man could do to change anything. Cornwell had fast been becoming a cynic.

Except that somehow through the fog of liquor and gloom they had both agreed that one man could perhaps do something on a very small scale, something that would do nothing whatsoever to right all the world's wrongs, but something that might make a difference to one other life, or perhaps two lives or a dozen lives or twenty.

And so the idea for the project had been born. The Marquess of Denbigh had provided the captial and the moral support-and a good deal of time and love too. He had been surprised by the latter. How could one love riffraff-and frequently foulmouthed and rebellious riffraff at that? But he did. Spence had gathered the children-abandoned orphans, thieving ruffians who had no other way by which

to survive, gin addicts, one sweep's boy, one girl who had already been hired out twice by her father for prostitution. And Mrs. Harrison had been employed to care for the girls.

They lived in two separate houses in the village, the boys in one, the girls in the other, six of each at first, now ten, perhaps twenty with more houses and more staff in the coming year. Two years of heaven and hell all rolled into one, according to Spence's cheerful report. In that time they had lost only one child, who had disappeared without trace for a long time. Word had it eventually that he was back at his old haunts in London.

The marquess wondered how Judith would react to sharing a house with twenty slum children for Christmas. He should have warned her, he supposed, told her and her sister-in-law the full truth. Undoubtedly he should have. He always warned his other guests, gave them an opportunity to refuse his invitation if they so chose.

He watched the scenery grow more familiar beyond the carriage windows. It would be good to be home again. He had been happy there for three years, since the death of his father. Or almost happy, at least. And almost not lonely. He had good neighbors and a few good friends. And he had the children.

Watching the approach of home, the events of the past two weeks began to seem somewhat unreal. And he wondered if he had done the right thing, dashing up to London as soon as word reached him that she was there. And concocting and putting into action his plan of revenge-a plan to hurt as he had been hurt.

But of course it was not so much a question of right and wrong as one of compulsion. Should he have resisted the urge-the need-to go? Could he have resisted?

The old hatred had lived dormant in him for so long that he had been almost unaware of its existence until he heard of the death of her husband. Perhaps it would have died completely away with time if Easton had lived. But he had not, and the hatred had surfaced again.

"When is this punishment to end?" she had asked him just two days before.

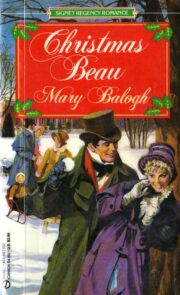

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.