occasionally, instead of" always with her and Amy. If only the man were not the Marquess of Denbigh! Perhaps she should have gone to Andrew's family for Christmas after all, she thought fleetingly.

Amy exclaimed over the Crown Jewels, and Kate, in Judith's arms, gazed at them silent and wide-eyed.

"Pretty, Mama," was all she said, pointing at a crown.

Judith looked at the armory and even at a few of the instruments of torture, which the marquess explained to Rupert and Amy. But she refused to look at the block and ax. She turned away with Kate while Rupert laughed and jeered.

"I should stay with you, Judith," Amy said. "All this is quite ghastly. But I must confess that it is also fascinating."

Somehow, as they were strolling away from the White Tower on their way back to the carriage, it happened that the children hurried ahead with Amy to gaze down into the moat and Judith was left walking beside the marquess.

"You have recovered?" he asked. "You looked for a few minutes as if you were about to faint."

"It is horrible," she said, "what human beings can do to other human beings."

"You do not believe, then," he said, "that criminals should be punished?"

"Of course," she said. "But torture? And execution by ax?"

"Many criminals have themselves used cruelty," he said. "Many have killed or betrayed their country. Do they not deserve to be treated accordingly? Do you not believe in execution, Mrs. Easton?"

"I don't know," she said. "I suppose I do. Anyone who kills deserves to die himself-I suppose. But what sort of an example do we set thieves and murderers when we return brutality for their brutality-in the name of law? It does not quite make sense."

"I would guess that you have never witnessed a hanging at Tyburn," he said. "Some people would not miss such an entertainment for all the world."

She shuddered and raised a gloved hand to her mouth.

And then her other hand was taken in a firm clasp and drawn through his arm.

"Your son loves animals," he said. "He was telling me all about his grandfather's dogs, particularly the one shaggy fellow which is allowed inside the house."

"Shaggy?" she said. "That is its name, you know. Sometimes it is difficult to know which end is which. There are a few dogs at home too, but I would not allow any to be brought with us because London is not quite the place for pets, I believe. Besides, my father would not have taken kindly to having his home overrun by the animal kingdom."

"It is one advantage of living in the country," he said. "A great advantage for children. Animals were almost my only companions when I was growing up. Your children are fortunate that they have each other."

She looked up at him, startled. He had just given her almost the only human glimpse of himself she had ever had. He had no brothers and sisters. She had known that. She had never thought of what that might have meant to him. Son of the late Marquess of Denbigh, his mother dead since his infancy. An only child. Animals had been his only companions. Had he been lonely, then? But she did not want to start thinking of him as a person.

And she realized that she was strolling with him, her arm drawn firmly through his, conversing just as if they were friends or at least friendly acquaintances. She was relieved to see the moat ahead and Amy and the children standing on the bridge looking down into the water. She used the excuse of Kate's turning to wave a hand at her to withdraw her arm from the marquess's and hurry forward.

At least Kate had not fallen beneath his spell that afternoon, she thought a little spitefully as the child lifted her arms to be carried the rest of the distance to the carriage.

But even that triumph was to be short-lived. When they were seated in the carriage, Kate wriggled off Judith's lap and climbed onto the marquess's. He continued naming to Rupert all the towers in the outer walls and pointing them out through the windows as they drove away. But he opened the top two buttons of his greatcoat, drew out his quizzing glass on its black ribbon, and handed it to Kate.

She played with it quietly for a while before lifting it to her eye and peering through it at her brother. Rupert shrieked with laughter.

"Look at her eye!" he said, and Amy and Judith laughed too as Kate gazed from one to the other, the glass held to one hugely magnified eye.

The children laughed and giggled for the rest of the journey. It was a merry homecoming.

Amy as well as Judith was one of Claude Freeman's party at the theater on the evening of the following day. The marquess was there too, and came to pay his respects between acts. Fortunately, Judith found, talking determinedly with Mrs. Fortescue, who was also one of their party, he directed his attentions and his conversation to Amy.

Amy was enchanted and as excited as any child being given a rare treat. She had never been to the theater before and had never seen so many splendidly dressed people all gathered in one place. Best of all, she thought, gazing about her, no one was staring at her. She was a very plain, very middle-aged lady, she told herself. Not a monster. Sometimes her family members had protected her-or themselves-so closely that she had felt as if she must be some freak of nature.

"I cannot believe all the splendor of it," she told the Marquess of Denbigh. "The velvet and gold and the chandeliers. And the acting. I was never so well entertained in my life."

"It is your first visit to the theater?" he asked, his eyes looking kindly at her.

And she realized that her reactions must appear very naive to him. But she did not care. The marquess, for all his splendor and very handsome looks and impressive title, would not laugh at her. He was a kind gentleman and she liked him excessively. If only Judith…

But Judith was pointedly talking to someone else and for some reason did not like the marquess. Or else she felt

embarrassed about what had happened all those years ago.

But Lord Denbigh had clearly forgiven her for that and was quite as clearly trying to fix his interest with her no matter how hard Judith tried to deny the fact.

She wished she had Judith's chance, Amy thought a little wistfully. Not with the marquess, of course. That would be ridiculous.

"The play is about to resume, ma'am," Lord Denbigh said, getting to his feet. "I shall take my leave of you and look forward to escorting you to St. Paul's tomorrow."

He took her hand and raised it to his lips. Amy felt ridiculously pleased. She felt even more pleased when he glanced toward Judith, although Judith was studiously looking the other way.

At St. Paul's the following day they wandered in some awe about the nave, dwarfed by the hugeness and majesty of the cathedral. Judith had never been there before. She had never been comfortable with heights, but the Whispering Gallery did not look too high up when one looked from below-the dome still soared above it-so she agreed to Rupert's persuasions and climbed the stone steps resolutely. Amy stayed down below with Kate.

But she felt the bottom fall out of her stomach when she stepped out onto the gallery, which circled the base of the dome. The nave of the cathedral looked very far down, the people there like ants. She did not even look long enough to distinguish Amy and Kate.

Rupert was running around the gallery, the marquess strolling after him. She stood against the wall, her palms resting against it at her back, willing her heart to stop thumping and her legs to regain their bones. She took a few tentative sideways steps. She looked nonchalantly about her but not down. It still seemed a very long way up to the top of the dome and the Thornhill frescoes painted there.

"It has nothing to do with cowardice, you know." She had not even noticed the Marquess of Denbigh coming back toward her. "It is an actual affliction that some people have. Your head can tell you that the gallery is broad and well

railed, that there is no possible way you can fall. But still you can be paralyzed with terror. A friend who suffers in the same way has told me that it is not so much the fear of falling as the fear of jumping. Is that right?"

He was standing in front of her, perfectly at ease, filling her line of vision. He spoke quietly, as he usually did. For once in his presence she felt her heart quieting.

"Yes," she said. "It is a very annoying terror. One feels like the typical helpless woman."

"The friend I spoke of," he said, "is a man and weighs fifteen stone if he weighs an ounce and is as handy with his fives as any pugilist one would care to meet. Take my arm. Your son, you will see, is across from us, waving down to his sister and his aunt."

Judith felt her stomach somersault again.

"He is perfectly safe," he said, "and will be delighted if we join him there. Walk next to the wall and imagine that we are strolling in Hyde Park. Look at my arm, if you wish, or at my shoulder. You have a lively and curious son. You must look forward to nurturing his curiosity."

No, she thought firmly as she told him of her own plans to employ a tutor for a few years and the plans of her brothers-in-law to send him to school when he was older-Rupert would after all be head of the family after the passing of his grandfather-no, she would not grow to like him. She would not mistake his behavior either here and now or briefly at the Tower for kindness.

There was no kindness in the Marquess of Denbigh. Only a cold, calculating mind. Only the desire to punish her by winning the affection of her children and by inflicting his unwanted company on her and by making her look foolish and rejected in the eyes of society.

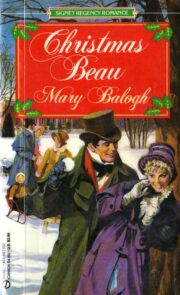

"Christmas Beau" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Christmas Beau". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Christmas Beau" друзьям в соцсетях.