‘What is it?’ He was watching her tensely.

‘I thought I heard something. A horn…’

He was at the window in two strides, leaning out, staring down the glen. The silence in the room was intense. Then he turned back to her, disappointment clear on his face. ‘I can see nothing.’

‘He will come,’ Eleyne said firmly.

IX

In the silence of the stillroom she peered around, her candle held high. The room was so full of memories; so many deaths: Donald, Gratney, William, Elizabeth, Muriel; so many illnesses cured: childhood snuffles and croups, broken bones, earaches and headaches and wounds. So many visions, conjured from the flames with the aid of mugwort and apple and ash and rosemary and lavender and thyme. The air was heavy with the fragrance of dried herbs, the beams hanging with this year’s crop. Taking a small linen bag from the hook beneath the high workbench, she went deftly from jar to jar collecting what she needed. Then she blew out the candle.

As she did every evening, she stopped in the nursery to say goodnight to her grandchildren. They were asleep together, bathed and in clean nightgowns, two small dark heads on the pillow. She stood looking down at them, smiling, then stiffly she bent to kiss each one in turn. ‘Sweet Bride keep you safe.’ Her knuckles were white on the handle of her stick, and suddenly her eyes were full of tears.

The castle was silent. On the walls the watch patrolled up and down, their eyes ever straining for a sign of siege ladders or engines being pushed closer under cover of darkness. In the smithy Hal Osborne leaned against the wall, chewing a stalk of barley between his teeth. His leg ached unbearably. Beyond him, in the back of the small heather-thatched building which was his home and place of work, his wife and two children slept on their straw pallets. She was a local girl, from a farm beyond the village. One day it would be his and then it would be his sons’. His chest tightened with love as he listened to the small snoring sounds his younger son made as he slept, his throat clogged by mucus. If the castle was taken that child would die, both his children would die, and his wife too, after she had been raped a dozen times.

Unless.

Silently he stood up. The English envoy had made the position clear. There was money and safety waiting for the man who gave Kildrummy Castle to the English.

On silent feet he walked across the courtyard, feeling the cold cut of the wind from the hills. The place was deserted. He made his way across to the bakehouse, where the ovens were already heating to bake the morning’s bread. Only one woman was there, sleepily feeding firewood to the blaze. Behind her the long trays of barley loaves lay on a table, proving beneath their linen cloths. Her face lightened when she saw Hal. ‘It’s early, my friend. If you’ve come for breakfast you’re too soon.’ Her arms were still floury; but there were smears of soot across her apron.

He eyed her for a moment, wondering what would happen to her. She was a cheerful motherly soul; at least four children played round her skirts when she was away from her duties in the kitchen. He remembered her. She wasn’t part of the castle household. She was the baker’s wife from Mossat. He could see the signs of the siege on her face – the drawn lines around her mouth, the black circles beneath her eyes, the thinness of her arms. Her husband had taken his bow and his sword and gone at the very beginning with the first muster of men.

For a moment he hesitated.

‘Out of my way.’ She bustled around him busily. ‘I’ve no one to help this morning. If you’ve nothing to do but stand around like a gowk, you can help me put the bread in the ovens. The castle will be awake at first light.’

He shook his head slowly. ‘I’ve duties to perform, mistress. I need a light for my lantern.’ He produced the horn lantern which used to hang above the door of the smithy in the hours of darkness.

She tossed her head. ‘Take it then, and get out of my way.’ Already she had turned away to her loaves.

He took a spill and thrust it into the fire. The tallow candle in the lantern lit easily, burning with a feeble flickering flame which stank immediately of rancid meat as, carefully, he shut the transparent horn door. He grinned at her uncomfortably. He wanted to say something, something to prepare her, but there was nothing he could say. He turned away and vanished into the pre-dawn dark. Within seconds she had forgotten that he had been there.

The great hall, the mekill hall, the people of Kildrummy called it, was virtually empty when he pushed the door ajar and slipped into the smoky darkness. A few figures slept on straw pallets around the hearth, but there was no fire there. The smoke in the air was an echo from long-dead fires trapped in the cold air below the high vaulted roof.

The lantern light was too faint to light much more than a foot or two around him. Silently he crept towards the largest pile of sacks. There was barley, oats, a little wheat for the countess’s table and stacked straw sheaves, bound into bales and piled into heaps which reached higher than a man. He glanced round. No one was awake. No one had seen him.

Slipping behind one of the piles he opened the door of the lantern. Pulling a handful of straw from one of the sheaves, he thrust it inside and held it above the candle. In seconds it had caught. It burned with a fierce crackle in the silence, but still no one had awakened. With fear catching at his throat, he swiftly drew the burning straw across the base of the nearest pile of sheaves, seeing the sparks catching in a bright trail. Hurrying now, he turned to another pile then another and another, hearing the crackle behind him growing louder. A murmur came from the far side of the hall and he heard a sudden shout. Hurling his lantern high into the pile of stacked sacks, he turned and dived for the door. Coughing, his eyes streaming from the acrid smoke, he ran silently down the side of the hall and dived through the darkness to his smithy. Running inside he stooped and shook his wife awake. ‘Bring the children! Hurry! We’re getting out of here.’

‘What is it? What’s happened?’ Sleepily she sat up, then in the open doorway she saw the first glow of fire. ‘What is it, Hal? What’s happened?’

‘The castle is being attacked,’ he said grimly, ‘but you and I will be safe. Come quickly. Follow me.’ He snatched up the sleepy boy and ran for the doorway.

The first tocsin began to ring as he stepped out into the courtyard and he could hear angry, frightened shouts from the watch. Someone ran across in front of him, a bucket in each hand from the deep well in the base of the Snow Tower – he could see the water slopping uselessly on to the dry cobbles.

He ran swiftly towards the gatehouse, his son clutched in his arms. Behind him he could smell the smoke now, and hear the crackle of the fire as the vast stockpile of grain and fodder in the hall caught. The noise was growing louder – turning into a dull roar.

Beside him a man appeared: the watch from the gatehouse tower. He was running towards the hall, shouting. He passed so close, Hal could have reached out and touched him, then he was gone, plunging into the smoke which billowed from the double doors of the great hall, leaving his post unmanned.

Hal smiled grimly. Putting the child down, he felt his way along the wall to the narrow stairway which led up into the winding chamber. There the windlass stood which raised the portcullis. Normally it took several men to work it, but his desperation gave him the strength of several men. Spitting on his calloused palms, he braced himself against the bar and began to push, his muscles straining and bulging. For a long moment nothing happened, then there was a groan from the pulley which led to the heavy counterweights in the ceiling. Sweat poured off him. He shut his eyes and pushed harder, hearing from below the lost wail of the little boy, waiting in the dark, and the terrified voice of his wife comforting him as they hid in the shadows. The sound gave him strength. Another superhuman shove and the windlass began to turn. Outside, beneath the gatehouse, slowly the portcullis began to rise. When it was only halfway up he knocked in the oak wedge and, his muscles screaming with agony, threw himself back down the stairs. Ducking under the ominously hanging spikes of the portcullis he reached the iron-studded gates and felt along them until he touched the passdoor with its triple bars. It was pitch-black in the shadow of the gatehouse. Gritting his teeth he heaved at the first bar. It was jammed. He pulled harder and at last it slid from its slots and fell to the ground. The second was easier, and the third. Grasping the heavy ring handle, he turned it and pulled the door open. Beyond it, the black barrier of the raised drawbridge barred the way.

He could hear Ned crying, the boy’s thin wail a lonely frightened sound beneath the echoing arch of the gateway. Ignoring the cry grimly, Hal threw himself at the wheel which controlled the drawbridge. It was wedged by a pin; he needed something to strike it free. Desperately he groped around. But there was nothing there.

Behind him there was a deafening crash. Part of the roof of the great hall had fallen in. The flames which shot up into the sky roared like demons in the night. For a fraction of a second he stopped and turned to stare, awed by what he had done. Then his eye was caught by the glint of steel in the light of the flames, and he saw the rack of axes on the wall near the watchman’s door. Seizing one, he swung it in his powerful arms and struck out the pin in one swift stroke. With a rumble and creak, the drawbridge began to fall on its counterweights as the first ladders were thrown up against the undefended walls by the enemy outside.

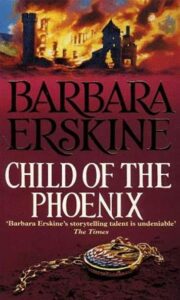

"Child of the Phoenix" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Child of the Phoenix". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Child of the Phoenix" друзьям в соцсетях.