“I would I might say the same!” returned Mr Steane. “Alas that we should meet, sir, under such unhappy circumstances!”

The Viscount looked surprised. “I beg your pardon?”

“Lord Desford, I have much to say to you, but it would be better that I should speak privately to you!”

“Oh, I have, no secrets from Miss Silverdale!” said Desford.

“My respect for a lady’s delicate sensibilities has hitherto sealed my lips,” said Steane reprovingly. “Far be it from me to ask a question that might bring a blush to female cheeks! But I have such a question to put to you, my lord!”

“Then by all means do put it to me!” invited Desford. “Never mind Miss Silverdale’s sensibilities! I daresay they aren’t by half as delicate as you suppose—in fact, I’m quite sure they are not! You don’t wish to retire, do you, Hetta?”

“Certainly not! I have not the remotest intention of doing so, either. I cut my eye-teeth many years ago, Mr Steane, and if what you have already said to me failed to bring a blush to my cheeks it is not very likely that whatever you are about to say will succeed in doing so! Pray ask Lord Desford any question you choose!”

Mr Steane appeared to be grieved by this response, for he sighed, and shook his head, and murmured: “Modern manners! It was not so in my young days! But so be it! Lord Desford, are you betrothed to Miss Silverdale?”

“Well, I certainly hope I am!” replied the Viscount, turning his laughing eyes towards Henrietta. “But what in the world has that to say to anything? I might add—do forgive me!—what in the world has it to do with you, sir?”

Mr Steane was not really surprised. He had known from the moment Desford had entered the room, and had exchanged smiles with Henrietta, that a strong attachment existed between them. But he was much incensed, and said, far from urbanely: “Then I wonder at your shamelessness, sir, in luring my child away from the protection of her aunt’s home with false promises of marriage! As for your effrontery in bringing her to your affianced wife—”

“Don’t you think,” suggested the Viscount, “that foolhardiness would be a better word? Or shall we come down from these impassioned heights? I don’t know what you hope to achieve by mouthing such fustian rubbish, for I am persuaded you cannot possibly be so bacon-brained as to suppose that I am guilty of any of these crimes. The mere circumstance of my having placed Cherry in Miss Silverdale’s care must absolve me from the two other charges you have laid at my door, but if you wish me to deny them categorically I’ll willingly do so! So far from luring Cherry from Maplewood, when I found her trudging up to London I did my possible to persuade her to return to her aunt. I did not offer her marriage, or, perhaps I should add, a carte blanche! Finally, I brought her to Miss Silverdale because, for reasons which must be even better known to you than they are to me, my father would have taken strong exception to her presence under his roof!”

“Be that as it may,” said Mr Steane, struggling against the odds, “you cannot—if there is any truth in you, which I am much inclined to doubt!—deny that you have placed her in a very equivocal situation!”

“I can and do deny it!” replied the Viscount.

“A man of honour,” persisted Mr Steane, with the doggedness of despair, “would have restored her to her aunt!”

“That may be your notion of honour, but it isn’t mine,” said the Viscount. “To have forced her into my curricle, and then to have driven her back to a house where she had been so wretchedly unhappy that she fled from it, preferring to seek some means, however menial, of earning her bread to enduring any more unkindness from her aunt and her cousins, would have been an act of wicked cruelty! Moreover, I hadn’t a shadow of right to do it! She begged me to carry her to her grandfather’s house in London, hoping that he might allow her to remain there, and convinced that if he refused to do that he would at least house her until she had established herself in some suitable situation.”

“Well, if you thought he’d do any such thing, either you don’t know the old snudge, or you’re a gudgeon!” said Mr Steane. “And from what I can see of you it’s my belief you’re the slyest thing in nature! Up to every move on the board!”

“Oh, not quite that!” said Desford. “Only to your moves, Steane!”

“You remind me very much of your father,” said Mr Steane, eyeing him with considerable dislike.

“Thank you!” said Desford, bowing.

“Also that young cub of a brother of yours! Both of a hair! No respect for your seniors! A pair of stiff-rumped, bumptious bouncers! Don’t think you can put the change on me, Desford, trying to hoax me with your Banbury stories, because you can’t!”

“Oh, I shouldn’t dream of doing so!” instantly replied his lordship. “I never compete against experts!”

Henrietta said apologetically: “Pray forgive me, but are you not straying a little away from the point at issue? Whether Desford was a gudgeon to think that Lord Nettlecombe would receive Cherry, or whether he thought what any man must have thought, doesn’t seem to me to have any bearing on the case. He did drive her to London, only to find Lord Nettlecombe’s house shut up. He then brought her to me. What, Mr Steane, do you suggest he should rather have done?”

“Thrown in the close!” murmured the Viscount irrepressibly.

“I must decline to enter into argument with you, ma’am,” said Steane, with immense dignity. “I never argue with females. I will merely say that in accosting my daughter on the highway, coaxing her to climb into his curricle, and driving off with her his lordship behaved with great impropriety—if no worse! And since he abandoned her here—if she is here, which I gravely doubt!—what has he done to redress the injury her reputation has suffered at his hands? He would have me think that he sought my father out in the belief that he would take the child to his bosom—”

“Not a bit of it!” interrupted Desford. “I hoped I could shame him into making her an allowance, that’s all!”

“Well, if that’s what you hoped you must be a gudgeon!” said Mr Steane frankly. “Not that you did, of course! What you hoped was to be able to fob her off on to the old man, and you wouldn’t have cared if he’d offered to engage her as a cook-maid as long as you were rid of her!”

“Some such offer was made,” said Desford. “Not, indeed, by your father, but by your stepmother. I refused it.”

“Yes, it’s all very well to say that, but how should I know if you’re speaking the truth? All I know is that I return to England to find that my poor little girl has been tossed about amongst a set of unscrupulous persons, cast adrift in a harsh world—”

“Take a damper!” said the Viscount. “None of that is true, as well you know! The unscrupulous person who cast her adrift is yourself, so let us have less of this theatrical bombast! You wish to know what I have done to redress the injury to her reputation she has suffered at my hands, and my answer is, Nothing—because her reputation has suffered no injury either at my hands, or at anyone else’s! But when I found that your father had gone out of town, the lord only knew where, and that Cherry had nowhere to go, not one acquaintance in London, and only a shilling or two in her purse, I realized that little though I might like it I must hold myself responsible for her. With your arrival, my responsibility has come to an end. But before I knew that you were not dead, but actually in this country, I drove down to Bath, to take counsel of Miss Fletching. I was a day behind you, Mr Steane. Miss Fletching most sincerely pities Cherry, and is, I think, very fond of her. She offers her a home, until she can hear of a situation which Cherry might like. She has one in her eye already, with an invalid lady whom she describes as very charming and gentle, but all depends upon her present companion, who is torn between her duty to her lately widowed parent, and her wish to remain with her kind mistress.”

“Oh, Des, it would be the very thing for Cherry!” Henrietta cried.

“What!” ejaculated Mr Steane, powerfully affected. “The very thing for my beloved child to become a paid dependant? Over my dead body!” He buried his face in his handkerchief, but emerged from it for a moment to direct a look of wounded reproach at Desford, and to say in a broken voice: “That I should have lived to hear my heart’s last treasure so insulted!” He disappeared again into the handkerchief, but re-emerged to say bitterly: “Shabby, my Lord Desford, that’s what I call it!”

Desford’s lips quivered, and his eyes met Henrietta’s, which were brimful of the same appreciative amusement that had put to flight his growing exasperation. The look held, and in each pair of eyes was a warmth behind the laughter.

Mr Steane’s voice intruded upon this interlude. “And where,” he demanded, “is my little Charity? Answer that, one of you, before you make plans to degrade her!”

“Well, I am afraid we can’t answer it just at this moment!” said Henrietta guiltily. “Desford, you will think me dreadfully careless, but while I was visiting an old friend this morning, Cherry went out for a walk, and—and hasn’t yet come back!”

“Mislaid her, have you? I learned from—Grimshaw—that she’s missing, but I don’t doubt she has done nothing more dangerous than lose her way, and will soon be back.”

“If she has not been spirited away,” said Mr Steane darkly. “My mind is full of foreboding. I wonder if I shall ever see her again?”

“Yes, and immediately!” said Henrietta, hurrying across the room to the door. “That’s her voice! Heavens, what a relief!”

She opened the door as she spoke. “Oh, Cherry, you naughty child! Where in the world—” She broke off abruptly, for a surprising sight met her eyes. Cherry was being carried towards the staircase by Mr Cary Nethercott, her bonnet hanging by its ribbon over one arm, a mutilated boot clutched in one hand, and the other gripping the collar of Mr Nethercott’s rough shooting-jacket.

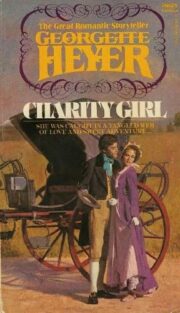

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.