In fact, it was delayed for longer than the Viscount had anticipated, for his journey south was not attended by the good fortune which had made his northward journey so speedy. A series of mishaps befell him, the most serious of which, the loss of a tyre, kept him kicking his heels for a day and a half, this accident occurring on the first day out from Harrowgate, which happened to be a Saturday, midway between Chesterfield and Mansfield. By the time the chaise bumped its way into Mansfield it was too late for the necessary repair to be effected, and on the Sunday the premises of both the wheelwright and the blacksmith were found to be closed: the one because its owner was a stern opposer of Sunday Travel; the other because the smith had gone off to spend the day with his married sister. It was not until Monday morning was merging into Monday afternoon that a new tyre was fitted to the wheel, and the Viscount was able to proceed on his way. And then (proving to him his belief that his luck had run out) one of his wheelers went dead lame, so that his progress to the next post-house more nearly resembled a funeral cortege than the swift journey of a gentleman of wealth and fashion. What with this, and several minor hindrances, it was four days before he reached Dunstable, where he decided to put up for the night, since there were still almost thirty miles to cover to Inglehurst, and he had no wish to arrive there long after the dinner-hour.

So it was not until a fortnight after he had deposited Cherry at Inglehurst that Henrietta, a little before noon, was at last gratified by having him ushered into her presence. Grimshaw announced him, in a sepulchral voice, and she started up out of her chair in front of the writing-desk, exclaiming impulsively: “Oh, Des, I am so thankful you’ve come at last!”

“Good God, Hetta, what’s amiss?” he demanded, brought up short in his advance across the room.

“Nothing!—that is to say, I hope nothing, but I am much afraid that things are beginning to go amiss.” He had taken her hands in his, and kissed them both, and was still holding them in his strong clasp, but she gently drew them away, and said, scanning his face: “Your errand hasn’t prospered, has it?”

He shook his head. “No. Nettlecombe has become an April-gentleman!”

Her eyes widened. “Married?”she asked incredulously.

“That’s it: leg-shackled to his housekeeper—oh, I beg her pardon! his lady-housekeeper!”

“Ah!” she said, with a twinkle of perfect comprehension. “No doubt she told you so herself!”

He grinned at her. “No, she told Nettlecombe, when he told me that he had married his cook. She said she would thank him to remember it, too, and I don’t doubt he will. Oh, Hetta, you can’t think how much I longed for you to be present at that interview! You must have laughed yourself into stitches!”

She moved to the sofa, and sat down, patting the place beside her. “Tell me!” she invited.

He did tell her, and she appreciated the story just as he had known she would. But he ended on a sober note, when, having described the final scene, in the corridor, he paused for an instant, before saying abruptly: “Hetta, I could not thrust that unfortunate child into such a household!”

“No,” she agreed, her own brow as troubled as his. “Only—Des, what is to be done with her? Mama said, a week ago, that if Nettlecombe repudiated her she had a good mind to keep her here, but—it wouldn’t do—I know it wouldn’t do! It is always the same when Mama takes a violent fancy to anyone! At first she thinks the new treasure perfect, and then she begins to perceive faults in her—and even when they are quite trivial faults she exaggerates them in her mind, and—which is worse!—remembers them, and adds them on to the next error her wretched favourite falls into!”

“Good God, has it come to that? Poor Cherry!”

“No, no, not yet!” she assured him. “But she has begun to criticize her—oh, not unkindly! merely noticing little innocent habits, or tricks of speech, and saying that she wishes Cherry would rid herself of them. And that odious woman of hers is so jealous of Cherry that she never loses an opportunity to drop poison into Mama’s ears. So far, she hasn’t succeeded in turning Mama against poor Cherry, but I own to you, Des, that I can’t persuade myself that—”

“Don’t tease yourself!” he interrupted. “There can be no question of Cherry’s remaining here! I never for a moment had such a solution to the problem in my mind. I had hoped to have left her with you only for a very few days, but I didn’t discover Nettlecombe’s whereabouts until Monday of last week, and even when I did discover that he had gone to Harrowgate I couldn’t induce his man of business to divulge his exact direction, and was obliged to spend the better part of two days scouring the town for him.”

“Oh, poor Des! No wonder you are looking so tired!”

“Am I? Well, if I am it’s only because I had the most devilish journey up from Yorkshire,” he said cheerfully. “No sooner did we get over one check than we fell into another, which is why I’m so late showing my front, as Horace would say. However, I’ve had time to decide what I had best do for Cherry—and that’s the most urgent matter I want you to consider, my best of friends!”

The door opened. “Mr Nethercott!” announced Grimshaw.

Cary Nethercott trod into the room, but checked at sight of the Viscount, and said: “I beg pardon! Grimshaw must have misunderstood me! I enquired for Lady Silverdale, and he ushered me into this room, where—where I can only trust that I am not intruding, Miss Hetta!”

“Not at all,” she responded, rising, and shaking hands with him. “You have already met Lord Desford, haven’t you?”

The gentlemen exchanged bows. Mr Nethercott said painstakingly that he had indeed had that pleasure, and the Viscount said nothing at all. Mr Nethercott then explained he had ridden over to bring Lady Silverdale his copy of the last number of the New Monthly Magazine, which contained an interesting article which he had mentioned to her ladyship on the occasion of his last visit, and which she had expressed a desire to read.

“How very kind of you!” said Henrietta. “She has gone for a stroll in the shrubbery, with Miss Steane.”

“Oh, then I will take it to her myself!” he said, his cheeks slightly reddening. “I shall hope to see you again presently, Miss Hetta!” He then said: “Your servant, sir!” and bowed himself out of the room.

The Viscount, who had been eyeing him with disfavour, hardly waited for the door to be shut before demanding: “Does that fellow live at Inglehurst, Hetta?”

“No,” replied Henrietta calmly. “He lives at Marley House.”

“Well, he seems to be here every time I come to visit you!” said the Viscount irritably.

She wrinkled her brow, and, after apparently cudgelling her memory, said, with a wholly spurious air of innocence: “But had you met him before you came to visit us on your way to Hazelfield?”

The Viscount ignored this home-question, and said: “I wonder which of us he thought he was hoaxing with his gammon about the New Monthly? Lord, what a fimble-famble!” He did not resume his seat, but glanced frowningly down at Henrietta, and said, with unaccustomed asperity: “I can’t conceive why you—No, never mind! What were we saying when that fellow interrupted us?”

“You were about to tell me what you have decided will be the best thing to do for Cherry,” she replied. “The most urgent question to be considered—or, rather, which you wish me to consider.”

“Yes, so I was. There are other things I should wish to talk about, but until I’ve provided for her Cherry must be my only concern.”

“Provided for her?” she repeated, her eyes lifting quickly to his face.

“Yes, of course. What else can I do but try to establish her comfortably? It was no doing of mine when she ran away from Maplewood, but when I drove her to London I became responsible for her: there’s no getting away from that, Hetta! Good God, what a shabster I should be if I abandoned her now!”

“Very true. What scheme have you in mind?”, she asked. “I have thought that—that marriage is the only answer to the problem, only—her parentage, and her want of fortune must stand in the way—don’t you think?”

He nodded, but said: “Not in the way of a man who fell in love with her, and had no need of a rich wife. But that’s for the future: my concern is for the immediate present. I’m going to Bath, to try if I can persuade Miss Fletching to help Cherry. Has she spoken to you about her? She was at Miss Fletching’s school, and talked to me about her on the way to London, saying how kind she had been.”

“Yes, indeed she has, and most affectionately, but when I suggested to her that she might return to that school, as a teacher, rather than hire herself out as a companion, she said Miss Fletching would have offered her that position if she had had enough learning, or enough skill on the pianoforte to teach music. Only she hadn’t. And I am afraid, Des, that that is true. Her only skill is in stitchery. She has the most amiable disposition in the world, but she is not at all bookish, you know. If Miss Fletching were to offer to take her I am very sure she would refuse, because she feels herself to be under a heavy obligation to her already.”

“I know she does. And if I were to pay Miss Fletching the debt that is owing to her—”

“No, Desford!” Henrietta said stringently. “You mustn’t do that! She is by far too proud to countenance such a thing!”

“Not, surely, if she supposed I had prevailed upon Nettlecombe to tip over the dibs!”

“If she believed you she would write to thank him.”

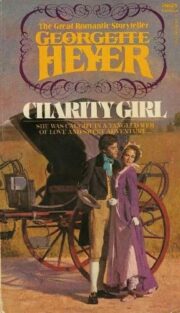

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.