“Exactly so, my lord!” said Tain, beginning swiftly to unpack the contents of the dressing-case. “I have myself seen three of them enter this house, one of them being an elderly lady of what one must call a garrulous disposition. I formed the opinion that if she were to subject your lordship to a description of her sufferings and of the cure which she is undergoing you would be hard put to it to maintain even the appearance of civility.”

“Then you were certainly right to procure a private parlour for me,” said the Viscount, laughing.

Leaving Tain to unpack his portmanteau, he sallied forth to continue his search for Lord Nettlecombe. He had already enquired for him at the Dragon and the Granby, without meeting with anything but blank looks and head-shakings, so, as the Chalybeate, under its imposing dome, lay on the opposite side of the green he thought he might as well make that his first port of call. If Lord Nettlecombe had come to Harrowgate for his health’s sake it seemed likely that he must by now have become a familiar figure there. But none of the attendants seemed to have heard of his lordship, the most helpful amongst them being unable to do more than suggest that he should be sought at the Tewit Well, which was the second of the two Chalybeates, situated half-a-mile to the west of the principal one.

Desford strode off, glad to be able to stretch his legs after having been cooped up for so many hours, but although he enjoyed a brisk walk it ended in another rebuff, accompanied by a recommendation to try the Sulphur Wells, at Lower Harrowgate, and the information that although the Lower town was a mile distant by road it was no more than half-a-mile away if approached “over the stile”. But as the directions given to him on how to reach the stile were as vague as such directions too often are, Desford decided to enquire at the inns and boarding-houses in High Harrowgate, before extending his search to the Lower town.

He very soon discovered that although Harrowgate was described by the Guide as consisting of two scattered villages this was another of that anonymous author’s misleading statements: no village that Desford had yet seen contained so many inns and boarding-houses as High Harrowgate. At none of those he visited was he able to obtain any news of his quarry, and by the time a church clock struck the hour of six, at which unfashionable time dinner was served at all the best inns, he was tired, hungry, and exasperated, and thankfully abandoned, for that day, his fruitless search.

When he reached the Queen he was considerably surprised by the respect with which he was greeted, the porter bowing him in, a waiter hurrying forward to discover whether he would take a glass of sherry before he went upstairs to his parlour, and the landlord breaking off a conversation with a less favoured guest to conduct him to the stairs, informing him on the way that dinner—which he trusted would meet with his approval—should be served immediately, and that he had taken it upon himself to bring up a bottle of his best burgundy from the cellar, and one of a very tolerable claret, in case my lord should prefer the lighter wine.

The reason for these embarrassingly obsequious attentions was soon made plain to the Viscount. Tain, relieving him of his hat and gloves, said that he had ventured to order a neat, plain dinner for him, consisting of a Cressy soup, removed with a fillet of veal, some glazed sweetbreads, and a few petit pates, to be followed by a second course of which prawns, peas, and a gooseberry tart were the principal dishes. “I took the precaution, my lord,” he said, “of looking at the bill of fare, and saw that it was just as I had feared: a mere ordinary, and not at all what you are accustomed to. So I ordered what I believe you will like.”

“Well, I am certainly hungry, but I couldn’t eat the half of it!” Desford declared.

However, when he sat down to table he found that he was hungrier than he had supposed, and he ate rather more than half of what was set before him. The claret, though not of the first growth, was better than the landlord’s somewhat slighting description of it had led him to expect; and the brandy with which he rounded off the repast was a true Cognac. Under its benign influence he began to take a more hopeful view of his immediate prospects, and to consider what his next move should be. He decided that the best thing he could do would be to visit first the Sulphur Well, and next, if he failed to come by any intelligence of Lord Nettlecombe’s whereabouts there, to discover the names and directions of the doctors practising in Harrowgate.

The experiences of the first wearing day he had spent in his search for Nettlecombe prevented him from feeling either surprise or any marked degree of disappointment when his enquiries at the Sulphur Well were productive of nothing more than regretful head-shakes; but he was a trifle daunted when presented with a list of the Harrowgate doctors: he had not thought that so many medical men were to be found in so small a spa. He betook himself to the Crown to study the list over a fortifying tankard of Home Brewed; and, having crossed off from it those who advertised themselves as Surgeons, and consulted a plan of both High and Low Harrowgate, which he had had the forethought to buy that morning, set out on foot to visit the first of the Lower town’s practitioners which figured on the list. Neither this member of the Faculty, nor the next on his list, numbered Lord Nettlecombe amongst his patients, but just as the Viscount was contemplating with disgust the prospect of spending the rest of the day in what he was fast coming to believe was an abortive search, fortune at last smiled upon him: Dr Easton, third on the list, not only knew where Nettlecombe was lodging, but had actually been summoned to attend him, when his lordship had suffered a severe attack of colic. “As far as I am aware,” he said, austerely regarding Desford over the top of his spectacles, “his lordship has not removed from that lodging, but since he has not again sought my services I do not claim him as a patient. I will go further! Should he again request my attendance upon him I should have no hesitation in recommending him to consult some other physician more willing than I am, perhaps, to being told that his diagnosis is false, and to having his prescription spurned!”

Resisting an absurd but strong impulse to offer Dr Easton an apology for Nettlecombe’s rudeness, Desford took his leave, saying that he was much obliged to him, and assuring him, with a disarming smile, that he had all his sympathy.

It transpired that Nettlecombe’s lodging was in one of the larger boarding-houses in the Lower town. It had an air of somewhat gloomy respectability, and was presided over by an angular lady whose appearance carried the suggestion that she must be in mourning for a near relation, since she wore a bombasine dress of sombre hue, without frills, or lace, or even a ribbon to lighten its sobriety. Her cap was of starched cambric, tied tightly beneath her chin; and as much of her hair as was allowed to be seen was iron-gray, and smoothed into bands as severe as her expression. She put Desford forcibly in mind of the dame in the village that lay beyond Wolversham who terrified the rural children into good behaviour and the rudiments of learning; and he would not have been in the least surprised to have seen a birch-rod on the high desk behind which she stood.

She was talking to an elderly couple, whose decorous bearing and prim voices exactly matched their surroundings, when Desford entered the house, but she broke off the conversation to direct a piercing look of appraisal at him, which made him feel that at any moment she would tell him that his neckcloth was crooked, or demand to know if he had washed his hands before venturing into her presence. His lips twitched, and his eyes began to dance, upon which her countenance relaxed, and, excusing herself to the elderly couple, she came towards him, saying, with a slight bow: “Yes, sir? What may I have the honour to do for you? If it is accommodation you are seeking, I regret I have none to offer: my house is always fully booked for the season.”

“No, I don’t want accommodation,” he replied. “But I believe you have Lord Nettlecombe staying here. Is that so?”

Her face hardened again; she said grimly: “Yes, sir, it is so!”

It was apparent that the presence of Lord Nettlecombe in her house afforded her no gratification, and that Desford’s enquiry had caused whatever good opinion she had formed of himself to wither at birth. When he requested her to have his card taken to my lord she gave a small, contemptuous sniff, and without deigning to reply, turned away to call sharply to a waiter just about to enter the long room: “George! Conduct this gentleman to Lord Nettlecombe’s parlour!”

She then favoured the Viscount with a haughty inclination of her head, and resumed her conversation with the elderly couple.

Amused, but also a trifle ruffled by this cavalier treatment, Desford was on the verge of telling her that when he had handed her his card he had intended it to be taken to Lord Nettlecombe, not laid on her desk, when it occurred to him that perhaps it would be as well not to give his lordship the opportunity to refuse to see him, so he suppressed the impulse to give this ridiculously uppish creature a set-down, and followed the waiter up the stairs, and along a corridor. The waiter, whose air of profound gloom argued a life of intolerable slavery, but was probably due to the pain of flat feet,. stopped outside a door at the end of the corridor, and asked what name he should say, and, upon learning it, opened the door, and repeated it in a raised, indifferent voice.

“Eh? What’s that?” demanded Lord Nettlecombe wrathfully. “I won’t see him! What the devil do you mean by bringing people up here without my leave? Tell him to go away!”

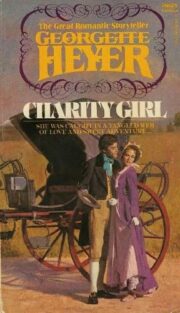

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.