But this Mr Crick would by no means permit him to do. He darted across the room to hold open the door for his distinguished visitor, bowing even more deeply than his clerk had done, and followed him down the dusty stairs, begging first his pardon and then his understanding of the delicacy of his own position as the trusted confidant of a noble client. The Viscount reassured him on both heads, but left him looking more harassed than ever. His last words, as Desford was about to mount into his tilbury, were that he hoped nothing he had said had given a wrong impression! Lord Nettlecombe had gone to try what the Harrowgate Chalybeate would do for his gout.

“Don’t tease yourself!” Desford said, over his shoulder. “I won’t disclose to his lordship that it was you who let slip the information that he had gone to Harrowgate!”

He then took his seat in the tilbury, recovered the reins from Stebbing, and drove off at a brisk trot, saying abruptly: “Didn’t my father go to Harrowgate once—oh, years ago, when he was first troubled by the gout! I was still up at Oxford, I think.”

Stebbing took a minute or two to answer this, frowning in an effort of memory. Finally he said: “Yes, my lord, he did. But, according to what I remember, he came home within a sennight, not liking the place. Unless it was Leamington he took against.” His frown deepened, but cleared after another few moments, and he said: “No, it wasn’t Leamington, my lord—though the waters never did him any good. It was Harrowgate right enough. And those waters didn’t do him any good neither—not but what there’s no saying that they wouldn’t have done him good if he’d drunk more than one glass, which tasted so bad it made him sick.”

The Viscount grinned appreciatively. “Poor Papa! Who shall blame him for going home? Did he take you there?”

“Me, my lord?” said Stebbing, shocked. “Lor’, no! In them days I was only one of the under-grooms!”

“I suppose you must have been. What a pity! I hoped you might know the place, for I don’t. Oh, well, we’d best stop at Hatchards, and I’ll see if I can come by a guide-book there!”

“My lord, you’re never going to go all that way just to find Miss’s grandpa?” exclaimed Stebbing. “Which—if you’ll pardon the liberty!—don’t seem to be a grandpa as anyone would be wishful to find!”

“Very likely not—indeed, almost certainly not!—but I’ve pledged my word to Miss Steane that I will find him, and—damn it, my blood’s up, and I will not be beaten!”

“But, my lord,” expostulated Stebbing, “it’ll take you four or five days to get there! It’s above two hundred miles away: that I do know, for when my lord and her ladyship went there, they were five days on the road, and Mr Rudford, which was his lordship’s valet at that time, always held to it that it was that which set up his lordship’s back so that he wouldn’t have liked the place no matter what!”

“Good God, you don’t imagine, do you, that I mean to go in the family travelling-carriage? What with four people in the carriage, the coachman, and I’ll go bail a couple of footmen outside, and a coach following, chuck-full of baggage, besides the rest of my father’s retinue, I’m astonished they weren’t a sennight on the road! I shall travel in my chaise, of course, taking Tain, and one portmanteau only, and changing horses as often as need be, and I promise you I shan’t be more than three days on the road. No, don’t pull that long face! If I can post to Doncaster in two days, which you know well I have frequently done, I can certainly reach Harrowgate in three days—possibly less!”

“Yes, my lord, and possibly more, if you was to have an accident,” said Stebbing. “Or find yourself with a stumbler in the team, or maybe a limper!”

“Or founder in a snowdrift,” agreed the Viscount.

“That,” said Stebbing coldly, “I didn’t say, nor wouldn’t, not being such a cabbage-head as to look for snowdrifts at this time o’year. But if you was to drop the high toby, who’s to say you won’t find yourself foundering in a regular hasty-pudding?”

“Who indeed? I’ll bear it in mind, and take care to stick to the post-road,” promised his lordship.

Stebbing sniffed, but refrained from further speech.

Desford was unable to find a guide-book of Harrowgate at Hatchard’s shop, but he was offered a fat little volume, which announced itself to be a Guide to All the Watering and Seabathing Places, and contained, besides some tasteful views, numerous maps, town-plans, and itineraries. He bore this off for perusal that evening, hoping to discover in the chapter devoted to the amenities of Harrowgate a list of the hotels and lodgings there. But although almost a dozen inns received favourable notice neither High nor Low Harrowgate appeared to boast of any establishment comparable to the hotels to be found at more fashionable watering-places; nor was any lodging-house mentioned. As he read what the unknown author had to say about the place, and pictured his father there, he was torn between appreciative amusement, and a strong wish that he himself were not obliged to go there. The very first paragraph was daunting, for it stated that because Harrowgate possessed “in a superior degree” neither the attraction of being fashionable, nor beauty of scenery, it was chiefly resorted to by valetudinarians. No doubt feeling that he had been rather too severe, the author bestowed some temperate praise on the situation of High Harrowgate, which he described as exceedingly pleasant, and commanding an extensive prospect of the distant country. But as, in the very next paragraph, he referred to the “dreary common” on which both High and Low Harrowgate were built, and to “the barren wolds of Yorkshire”, it seemed safe to assume that the place had not taken his fancy. Which, thought Desford, flicking over the pages which dealt with the qualities and virtues of the wells, and reading the passage headed Customs and Accommodations, was not to be wondered at. He could almost feel the hairs rising on his scalp when he read that one of the advantages enjoyed by visitors to Harrowgate was that the narrow circle of their amusements drew them into “something like family parties”; but when he read that the presence of the ladies sitting at the same board as the gentlemen excluded any rudeness or indelicacy, he began to chuckle; and when, on the next page, he learned that one of the advantages of mixing freely with the ladies was the sobriety it ensured—to which the author acidly added that to this the waters contributed “not a little”, he laughed so much that it was several moments before his vision was sufficiently clear to enable him to read any more. However, he did read more, and although he found no mention of a pump room, he did learn that there was an Assembly Room, and a Master of Ceremonies, who presided over the public balls; a theatre; two libraries; a billiard-room; and a morning lounge in one of the new buildings, called the Promenade; which made it seem probable that he would experience no very great difficulty in discovering where he could find Lord Nettlecombe.

But what he found very difficult to understand was why Lord Nettlecombe, who, so far from enjoying the company of his fellow men and women, had for years spurned even his oldest acquaintances, should have elected suddenly to spend the summer months where, according to the author of the Guide, repasts (served in the long rooms of the various inns) were “seasoned by social conversation”; and where “both sexes vied with each other in the art of being mutually agreeable”. It was possible, of course, that the circumstance of the expenses of living and lodging being moderate might have attracted his cheese-paring lordship; but this advantage must surely have been off-set by the cost of so long a journey. The Viscount, as he took his candle up to bed, wondered if Nettlecombe had travelled north on the common stage, but abandoned this notion, feeling that the old screw could not be such a shocking lick-penny as that. He might, with perfect propriety, have travelled on the Mail coach, but although this was much cheaper than hiring a private chaise it was by no means-dog-cheap, particularly when two places would have to be booked. Lord Nettlecombe might not travel in the rather outmoded state favoured by Lord Wroxton, but it was inconceivable to Desford that he could have gone away on a protracted visit without taking his valet with him. The thought of his high and imposing father’s regal process to Harrowgate, and his very brief stay there, made Desford begin to chuckle again. He must remember, he told himself, to ask Poor Dear Papa, at a suitable moment, for his opinion of Harrowgate.

Tain, his own extremely accomplished valet, had received without a blink the news that his lively young master meant to leave almost at crack of dawn for an unfashionable resort in Yorkshire; and when further told that he must pack whatever was strictly necessary into one portmanteau, he merely said: “Certainly, my lord. For how many days does your lordship mean to stay in Harrowgate?”

“Oh, not above two or three!” replied Desford. “I shan’t be attending any evening-parties, so don’t pack any ball-toggery.”

“Then one portmanteau will be quite sufficient for your lordship’s needs,” said Tain calmly. “Your dressing-case may go inside the chaise, and I shall not pack your Hessians, or any of your town-coats. I fancy they would be quite ineligible for wear in Those Parts.”

That was all he had to say about the projected expedition, either then or later; and Desford, who had had several years’ experience of his competence, never so much as thought of asking him whether he had packed enough shirts and neckcloths, and had found room for a change of outer raiment.

For his part, Tain showed not the smallest surprise at what he might have thought to be a very queer start, or betrayed by look or word that he was well aware of the Viscount’s purpose in going post-haste to Harrowgate, when his intention had been to attend the races at Newmarket. He had not yet seen Miss Steane, but he knew all about her meeting with the Viscount, for he stood on very friendly terms with both the Aldhams, and had contrived, without showing a vulgar curiosity unbecoming to a man of his consequence, to discover from them quite as much as they knew, and many of Mrs Aldham’s conjectures on the probable outcome of the adventure. On these he withheld judgment, feeling that he knew my lord far more intimately than they did, and having yet to see in him any of the signs of a gentleman who had fallen head over ears in love. He did not discuss the matter with Stebbing, not so much because it would have been beneath a gentleman’s gentleman to hobnob with a groom, but because he was as jealous of Stebbing as Stebbing was of him.

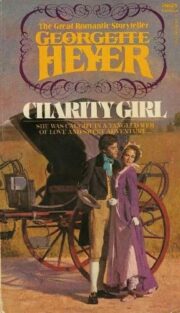

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.