“I should prefer to say, my lord, that it is not a mode which commends itself to me. Nor, if I may be pardoned for putting forward my opinion, one befitting a young gentleman of rank.”

“Well, you’re out there!” retorted Simon. “It’s the very latest style, and it was Petersham who started it!”

“My Lord Petersham, sir,” said Grimshaw, unmoved, , “is well known to be an Eccentric Gentleman, and frequently appears in a style that one can only call rather of the ratherest.”

“And besides which,” said Desford, as Grimshaw withdrew from the room, “Petersham is a good fifteen years older than you are, and he don’t look like a macaroni-merchant whatever he wears.”

“Take care, brother!” Simon warned him. “A little more to that tune and you will find yourself done to a cow’s thumb!”

Desford laughed, and surveyed the various dishes before him through his glass. “Shall I? No, really, Simon, those trousers are the outside of enough! However, I didn’t come to discuss your clothes: I’ve something more important to say to you.”

“Well, now you put me in mind of it I’ve something important to say too! It’s a lucky chance I dined here tonight. Lend me a monkey, Des, will you?”

“No,” responded Desford bluntly. “Or a groat, if it comes to that.”

“Quite right!” said Simon approvingly. “One should never encourage young men to break shins! Just make me a present of it, and not a word about this bud of promise you’re jauntering about with shall pass my lips!”

“What a stretch-halter you are!” remarked Desford, embarking on a raised pie. “Why do you want a monkey? Considering it isn’t a month since the last quarter-day it ought to be high tide with you.”

“Unfortunately,” said Simon, “the last quarter’s allowance was, so to say, bespoke!”

“And my father called me a scattergood!”

“That’s nothing to what he’ll call you, my boy, if he gets wind of your little charmer!”

Desford paid no heed to this sally, but directed a searching look at his brother, and asked: “I collect you’ve been having some deep doings: not let yourself be hooked into any of the Greeking establishments, have you?”

Simon smiled ruefully. “Only once, Des. I may be said to have bought my experience dearly.”

“Physicked you, did they? Well, it happens to us all. Is that what brought you home? Wouldn’t my father frank you?”

“To own the truth, dear boy, I haven’t dared to broach the matter, though that is what brought me home. It hasn’t yet seemed to me the moment to raise ticklish subjects. His mood is far from benign!”

“No wonder, if he saw you in that rig! What a fool you are, Simon! You might have known it would set him all on end!”

“No, no, how can you suppose me to be so wanting in tact? I clothed myself with the utmost propriety of taste. I even sought to gratify him by wearing knee-breeches for dinner, but knee-breeches have no chance of success against gout. I may add that having been obliged to listen to him cutting at me, you, and even Horace for over an hour this afternoon I seized the opportunity to escape, and very handsomely offered to bear Mama’s letter to Lady Silverdale in place of the groom she had meant to send with it. She felt it behoved her to write to enquire after Charlie. Did Hetta tell you that the silly cawker has knocked himself up?”

Desford nodded. “Oh, yes! How bad is he?”

“Well, he looks as sick as a horse, but they seem to think he’s going on pretty prosperously. Now, about that monkey, Des!”

“I’ll give you a cheque on Drummond’s—on one condition!”

Simon laughed. “I won’t breathe a word, Des!”

“Oh, I know that, codling! My condition is that you throw those clothes away!”

“It will be a sacrifice,” said Simon mournfully, “but I’ll do it. What’s more, if there’s any little thing you think I might be able to do for you in your present very odd situation I’ll do that too.”

“Much obliged to you!” said Desford, rather amused, but touched as well. “There isn’t anything—unless you chance to know where old Nettlecombe has loped off to?”

“Nettlecombe? What the devil do you want with that old screw?” demanded Simon, in considerable astonishment.

“My bud of promise, as you call her, is his granddaughter, and I’ve charged myself with the task of delivering her into his care. Only when we reached London we found he had gone out of town, and shut up his house. That’s why I brought her here.”

“Good God, is she a Steane?”

“Yes: Wilfred Steane’s only child.”

“And who the deuce may he be?”

“Oh, the black sheep of the family! Before your time! Before mine too, if it comes to that, but I remember all the talk that went on about him, and in particular the things Papa said of him, and every other Steane he had ever heard of! Which is why I don’t want him to get wind of Cherry!”

“Is that the girl’s name?” asked Simon. “Queer sort of a name to give a girl!”

“No, her name is Charity, but she prefers to be called Cherry. I met her when I was staying at Hazelfield. I don’t propose to take you into the circumstances which led me to bring her to London in search of her grandfather, but you may believe I was pretty well forced to do so. She was living with her maternal aunt, and being so shabbily treated that she ran away. I met her trying to walk to London, and since nothing would prevail upon her to let me take her back to her aunt what else could I do but take her up?”

“A regular Galahad, ain’t you?” grinned Simon.

“No, I am not! If I’d dreamed I should be dipped in the wing over the business I wouldn’t have done it!”

“You would,” said Simon. “Think I don’t know you? What, by the way, did the black sheep do to cause a scandal?”

“According to my father, just about everything, short of murder! Nettlecombe cast him off when he eloped with Cherry’s mother, but what forced him to fly abroad was being found out in Greeking transactions. Took to drinking young ‘uns into a proper state for plucking, and then fuzzed the cards.”

Simon opened his eyes very wide. “Nice fellow!” he commented. “What has become of him?”

“Nobody seems to know, but since nothing has been heard of him for some years he is generally thought to be dead.”

“Well, it’s to be hoped he is,” said Simon. “If you don’t mind my saying so, dear boy, the sooner you palm the girl off on to her grandfather the better it will be. You haven’t a tendre for her, have you?”

“Oh, for God’s sake—!” Desford exclaimed, “Of course I haven’t!”

“Beg pardon!” murmured Simon. “Only wondered!”

Chapter 7

Before the brothers parted that evening Simon had tucked into his pocket the Viscount’s cheque, and had asked him in a soft, mischievous voice if he meant to go to Newmarket, for the July Meeting. The Viscount answered that he had meant to go, but now saw little hope of it. “Ten to one I shall still be hunting for Nettlecombe,” he said. “But if you are going I rather fancy I can put you on to a sure thing: Mopsqueezer. Old Jerry Tawton earwigged me at Tatt’s last week, and he’s in general a safe man at the corner.”

Simon gripped his hand, smiling warmly at him, and said: “Thank you, Des. Dash it, you are a trump!”

Slightly surprised, Desford responded: “What, for passing on Jerry’s tip? Don’t be such a gudgeon!”

“No, not for that, and not even for this,” said Simon, patting his pocket. “For not reading me any elder-brotherly jobations!”

“Much heed you would pay to them if I did!”

“Oh, you never know! I might!” Simon said lightly. He picked up his hat, and set it at a rakish angle on his fair locks. He hesitated for a moment, and then said: “I shall go back to London tomorrow, and shall be fixed there until I go to Newmarket. So, if you do find yourself in a hobble, and think I might be able to help, come round to my lodgings, and—and I’ll do my best for you!” He added, returning to his insouciant manner: “You’ve no notion how nacky my best is! Goodbye, dear boy!”

The Viscount left Inglehurst some twenty minutes later relieved of at least one of his worries. Lady Silverdale, thanks largely to her dislike of Lady Bugle, and in some measure to Cherry’s modest demeanour, seemed inclined to look favourably upon her uninvited guest. It was perhaps fortunate that she did not think Cherry more than passably pretty. “Poor child!” she said. “Such a pity that she should be a little dab of a thing, and dress so dowdily! Hetta, my love, it would be only kind, I think, to make her rather more presentable; and I have been wondering whether, if you gave her that green cambric which we decided was not the colour for you, she might make herself a dress. Just a simple round dress, you know! And she must have her hair cropped, for I cannot endure untidy heads.”

Henrietta being very willing to encourage her parent in these charitable schemes the Viscount took his leave of both ladies, and went away feeling that, at least for the present, her hostess would treat Cherry kindly.

When he left the house Cherry was sunk in profound slumber, from which the noise of his chaise-wheel under her window, and the trampling of hooves on the gravel, did not even disturb her dreams. She was so tired after the exertions and the agitations of the day that she hardly stirred until one of the housemaids came in to draw back the curtains round her bed, expressing, as Cherry opened her drowsy eyes and stretched like a kitten, the hope that she had slept well, and informing her that it was a beautiful morning. In proof of this statement she drew back the window-blinds, making Cherry blink at the sudden blaze of sunlight that flooded the room. Cherry sat up with a jerk, remembering all the events of the previous day, and asked to be told what time it was. Upon hearing that it was eight o’clock, she gave a gasp of dismay, and exclaimed: “Oh, goodness I Then I must have slept for twelve hours! However did I come to do such a thing?”

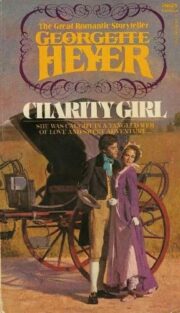

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.