She interrupted him, demanding: “Is it possible that she is Wilfred Steane’s daughter?”

“Yes, poor child! As good as orphaned, even if he should chance to be alive!”

“Desford!” she uttered, groping for her vinaigrette, “I little thought that you, of all people, would be so wanting in conduct as to bring that—that Creature’s child to Inglehurst! And how your aunt could—but I always thought poor dear Sophronia strangely freakish! But how she could have supposed that I should be willing to befriend the girl—”

“Oh, she didn’t, ma’am!” he interposed. “All she asked me to do was to take Cherry to her grandfather. It was I—knowing you much better than my aunt does!—who realized that if there was one person on whom I could depend to shelter this unfortunate girl that person is yourself!” He smiled at her, and added: “Are you trying to hoax me into believing that you are hard-hearted enough to repulse her? You won’t succeed: I know you too well!”

She plucked uncertainly at the fringe of the silk shawl she wore, eyeing him with resentment. Before she had made up her mind what to say to make him remove Cherry without impairing the vision he had of the saintliness of her own disposition the door opened, and Henrietta came in, leading Miss Steane by the hand.

“Mama, here is poor little Cherry, who has been having a horridly uncomfortable time, as I collect Desford will have told you. She is quite worn down by her troubles, but she would have me bring her to you before I tuck her into bed. Now, my dear, you can see for yourself that my mother is no more a dragon than I am!”

“So pleased!” said Lady Silverdale, in a faint voice, and favouring Cherry with a very slight inclination of her head. “Hetta, my love, my cordial!”

Quite dismayed, Cherry whispered: “I should not have come! Oh, I knew I should not! I beg your pardon, ma’am!”

Lady Silverdale was a selfish but not an unfeeling woman, and this stricken speech, coupled as it was with a face pale with weariness, considerably mollified her. It was clearly impossible to cast this miserable little girl out of the house, so although she maintained the attitude of one on the brink of sinking into a swoon, and continued to speak in a faint, long-suffering voice, she said: “Oh, not at all! You must forgive me if I leave it to my daughter to show you to your bedroom: I have been very unwell, and my medical attendant warns me that I must avoid all unnecessary exertion. So unfortunate that you should have come to visit us at just this moment! But my daughter will look after you. Pray tell me if there is anything you would wish for! A glass of hot milk, perhaps, before you retire to bed.”

“I fancy, ma’am, that she needs something more substantial than a glass of milk,” said the Viscount, perceiving that Cherry was looking quite crushed, and most improperly flickering a wink at her.

“Well, of course she does!” said Henrietta. “She is going to have supper as soon as I’ve tucked her into her bed.”

“Oh, thank you!” said Cherry gratefully. “I don’t feel I deserve to be given such a treat, but I would very much like it! Aunt Bugle never allowed me to have—”

She broke off in consternation, for these words had had a startling effect on her hostess. At one moment leaning limply back in her chair, and sniffing at her vinaigrette, she suddenly abandoned this moribund pose, sat bolt upright, and said sharply; “Who did you say?”

“M-my Aunt Bugle, ma’am,” faltered Cherry.

Lady Silverdale’s bosom swelled visibly. “That woman!” she pronounced awfully. “Do you mean to tell me she is your aunt, child?”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Cherry, trembling.

“Are you acquainted with her, Mama?”

“We were brought out in the same season!” disclosed Lady Silverdale dramatically. “I beg you will not speak to me of Amelia Bugle! A bouncing, flouncing young female, setting her cap at every single gentleman that crossed her path, and fancying herself to be a beauty, which she was not, for she had a deplorable figure, and a particularly ugly nose, and as for the pretentious airs she gave herself when she caught Bugle, and took to thinking herself the pink of gentility, I laugh whenever I remember them!”

Laughter did not appear to be her predominant emotion, though she did utter a Ha! of withering sarcasm. Henrietta, briefly meeting Desford’s dancing eyes, said, with a quivering lip: “We collect, Mama, that she wasn’t one of your bosom-bows!”

“Certainly not! But I remained on common civility terms with her until she had the effrontery to thrust herself before me in a doorway, saying, like the self-important mushroom she was, that she fancied she must take precedence since her husband’s baronetcy was an older creation than Silverdale’s! After that, of course, I never did more than bow to her, or felt the smallest interest in her. Come and sit down beside me, my dear child, and tell me all about her! I am persuaded she used you shamefully, for I recall that she was never used to waste a particle of politeness on people she considered to be beneath her. You did very right to leave her!”

She patted the place beside her on the sofa invitingly, and Cherry, swiftly recovering from her astonishment, smiled shyly, dropped a little curtsy, and accepted the invitation. The curtsy pleased Lady Silverdale; she was moved to press Cherry’s hand, and to say: “Poor child! There! You will not meet with Turkish treatment in this house! Is it true that That Woman has five daughters?”

Perceiving that her volatile parent was now wholly engrossed by the dreadful fate that had overcome her old rival, Henrietta seized the opportunity thus afforded her to exchange a few words with the Viscount. “Nothing could be more fortunate, could it?” she said, in an undervoice. “I wonder what That Woman really did to make Mama take her in such dislike?”

“Yes, so do I!” he returned. “I depend on you to discover the answer! Clearly, her want of delicacy in claiming precedence in that doorway can only have been the culminating impertinence!”

“I should suppose that they must have been rival beauties,” said Henrietta. “But never mind that! We will keep Cherry with us until you have found her grandfather, but what would you have me tell her to do? Should she not write a civil letter to Lady Bugle, informing her that she is at present residing at Inglehurst? I cannot think it right that she should leave her without a word! Lady Bugle cannot be so monstrous as to feel no anxiety about her!”

“No,” he agreed reluctantly. “At the same time—Hetta, tell her to write that she has gone to visit her grandfather! Dash it, I must be able to discover where he is in a very few days, and if she mentions Inglehurst she must surely connect me with the business, which will lead her to make enquiries of my Aunt Emborough, and then I shall be in the suds!”

“Couldn’t you write to Lady Emborough, explaining it all to her?” she suggested.

“No, Hetta, I could not!” he replied. “She doesn’t like Lady Bugle, but she don’t want to quarrel with her, and she wouldn’t thank me for embroiling her in this mingle-mangle!”

“Very true! I hadn’t considered that. It shall be as you wish. Do you mean to rack up here for the night, or are you going to Wolversham with Simon?”

“Neither: I’m going back to London. You can picture me tomorrow, scouring the town to find somebody able to give me Nettlecombe’s direction—and in all probability wasting my time! Ah, well! It will be a lesson to me, won’t it, not to rescue damsels in distress?”

“Not to venture to cross quagmires without making sure you don’t go in over shoes, over boots, at all events!” she said, laughing at him.

“Or at least without making sure that Hetta is there to pull me out!” he amended. He took her hand, and kissed it. “Thank you, my best of friends. I am eternally obliged to you!”

“Oh, fiddle! If you are to drive back to London this evening you had better take leave of your damsel now, because I mean to put her to bed immediately: she’s so tired she can scarcely keep her eyes open! I’ve instructed Grimshaw to set out a supper for you, and you’ll find Simon waiting to bear you company.”

“Bless you!” he said, and turned from her to bid his protégée farewell.

She got up quickly when she saw him coming towards the sofa, and he saw that she was indeed looking very tired. It was with an effort that she smiled at him, and tried to thank him for his kindness. He cut her short, patted her hand, and adjured her, in avuncular style, to be a good girl. He then promised Lady Silverdale that he would come to take his leave of her as soon as he had eaten his supper, and went off to the dining-room.

Here he found his brother seated sideways at the table, with one elbow resting on it, his long legs, in their preposterous Petersham trousers, stretched out before him, and the brandy decanter beside him. Grimshaw, wearing the expression of one whose finer feelings were grossly offended, bowed the Viscount to his chair and regretted that the dishes laid out before him were of a meagre nature, the lobster and the chickens having been consumed at dinner. Also, he added, in an expressionless voice, the almond cheesecakes, which Mr Simon had been pleased to esteem.

“What he means is that I finished the dish,” said Simon. “Devilish good they were too! I wish you will take that Friday-face away, Grimshaw! You’ve been wearing it the whole evening, and it’s giving me a fit of the dismals!”

“I daresay your new rig don’t take his fancy,” said the Viscount, helping himself to some pickled salmon. “And who shall blame him? It makes you look like a coxscomb. Wouldn’t you agree with me, Grimshaw?”

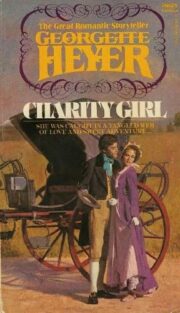

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.