“Oh, my God!” ejaculated the Viscount, in accents of the liveliest dismay.

She could not help laughing, but she said severely: “If a stranger heard you, Des, he couldn’t be blamed for thinking that you held your little brother in the most unnatural dislike!”

“Well, there aren’t any strangers present, and you know well enough that I don’t hold him in dislike,” said the Viscount impenitently. “But if ever there was a leaky rattle—! I shall be obliged to see him, I suppose, but if he don’t make me grease him handsomely in the fist to keep his tongue about this affair I don’t know young Simon!”

She cried shame on him, but in the event he was seen to know his graceless brother better than she did; for when he had talked her into making Cherry’s acquaintance, and judging for herself how innocent, and how much to be pitied she was, and had accompanied her to the Green saloon, the unwelcome sight of the Honourable Simon Carrington making himself agreeable to Miss Steane confronted him, and he had no difficulty in interpreting the sparkling look of mischief with which the Honourable Simon greeted him.

He ignored it, and presented Cherry to Miss Silverdale, saying easily: “I must warn you, Hetta, that I’ve brought this foolish child to you very much against her will! I strongly suspect that she fears I am handing her over to a dragon!”

Cherry, who had risen quickly to her feet, blushed and stammered, as she dropped a slight curtsy: “Oh, no, no! In—in-deed I d-don’t, ma’am!”

“Well, if she does think it I shall hold you entirely to blame, Desford,” said Miss Silverdale, moving forward, with her hand held out to Cherry, and a smile on her lips. “A pretty picture you must have drawn of me! How do you do, Miss Steane? Desford has been telling me of your adventures, and how you have been quite thrown out by finding that your grandfather is out of town. I can well imagine what your feelings must have been! But I expect Desford will find him very soon, and in the meantime I hope we can make you comfortable at Inglehurst.”

Cherry lifted her big eyes, brimming with grateful tears, to Henrietta’s face, and whispered: “Thank you! I am so sorry—!”

The Viscount, having watched this interchange with satisfaction, transferred his attention to his brother, and demanded, with revulsion: “For God’s sake, Simon, what kind of a rig is that?”

Henrietta said laughingly, over her shoulder: “Didn’t I tell you, Simon, that Des would utterly condemn it?”

Young Mr Carrington, a very dashing blade, was indeed wearing a startling habit, and the fact that he had the height and the figure to adopt any extravagant mode without appearing grotesque did nothing to recommend the style he had chosen to adopt to his elder brother. He was a goodlooking young man, full of effervescent liveliness, and as ready to laugh at himself as at his fellow-men. His eyes laughed now, as he said solemnly: “This, Des, is the highest kick of fashion, as you would know if you were as dapper-dog as you think you are!” He thrust one foot forward as he spoke, and indicated with a sweep of his hand the voluminous garments which clothed his nether limbs. “The Petersham trousers, my boy!”

“I am aware!” said the Viscount. He raised his quizzing-glass, and through it surveyed his brother from his heels to the inordinately high points of his shirt-collar. These were rivalled by the height of his coat collar, which rose steeply behind his head, and by the gathered and hugely padded shoulders of his coat. The sleeves of his coat were embellished with a number of buttons, those nearest to his wrists being left unbuttoned in a negligent style; and he wore round his neck a very large striped neckcloth. The Viscount, having taken in all these enormities, shuddered, and let his glass fall, saying: “Have you had the infernal brass to sit down to dine with Lady Silverdale in that rig, jackanapes?”

“But, Des, she begged me to do so!” said Simon, deeply injured. “She liked my beautiful new clothes, didn’t she, Hetta?”

“I rather think she was stunned by them,” Henrietta replied. “And by the time she had recovered from the shock you had flummeried her into inviting you to dine with us—playing off more cajolery than I’ve been privileged to see in a twelvemonth!”

“Oh, come, come!” instantly protested Simon. “It isn’t as long as that since you saw me last!”

She laughed, but turned from him to Cherry, who had been listening to this badinage with an appreciative twinkle in her eyes. Miss Silverdale perceived that Desford had spoken no less than the truth when he had described her as a taking little thing, and wondered, with an inexplicable sinking of the heart, if he was more captivated by her than he perhaps knew. Recognizing the tiny pang she felt as the envy of one who was neither little nor taking—besides being past the first blush of youth—of one who was young, and pretty, and little, and very taking indeed, she sternly repressed such ignoble thoughts, smiled at Cherry, and held out her hand, saying: “I must introduce you to my mother, but I am very sure you would wish to put off your bonnet and cloak first, so I shall take you up to my room, while Desford explains to my mother how it comes about that we are to have the pleasure of entertaining you for a little while. You will find Mama in the drawing-room, Des!”

He nodded, and would have followed her out of the saloon immediately had not Simon detained him, with a demand to know whether he meant to spend the night at Wolversham. “No, I am returning to London,” he replied. “But I want a word with you before I leave, so don’t you go home until we’ve had a talk!”

“I’ll be, bound you do!” said Simon, grinning impishly at him. “I won’t go!”

The Viscount threw him a speaking glance, and went off to try his own powers of flummery on Lady Silverdale.

He found her engaged, in a somewhat languid fashion, in embroidering an altar cloth, but she pushed the frame aside when he entered the room, and held out a plump hand to him, and saying, in a sweet, failing voice: “Dear Ashley!”

He kissed her hand, retained it in his own for a minute, and set about the task of cajoling her by paying her a compliment. “Dear Lady Silverdale!” he said. “Don’t think me abominably saucy!—How is it that you contrive to look younger and prettier every time I see you?”

If she had had the forethought to have provided herself with a fan she would undoubtedly have rapped his knuckles with it, but as it was she was obliged to content herself with giving him a playful slap, and saying archly: “Flatterer!”

“Oh, no!” he returned. “I never flatter!”

“Oh, what a farradiddle!” she said.

He denied it, and she accepted this with a complacency born of the knowledge that she had been, in her heyday, a remarkably pretty girl. Time, and a life of determined indolence, had considerably impaired her figure, but she was generally held to have great remains of beauty; and she had discovered that a fraise, or little ruff, admirably concealed a tendency to develop a double chin. A mild attachment to the late Sir John Silverdale had grown, during the years of her widowhood, to proportions which would have astonished that gentleman, and would not have outlived an offer for her hand made by another suitor of birth and fortune. None had come forward to woo the widow, so as much affection as she could spare from herself she had bestowed upon her only son. Such persons who were not intimately acquainted with her believed her to be passionately devoted to her children, which, indeed, she herself believed, but those who had the opportunity to observe her at close quarters were not deceived by her caressing manner: they knew that although she might fairly be said to dote on Charles she had only a tepid affection for Henrietta.

The Viscount was of their number, and he lost no time in enquiring solicitously into the state of Charlie’s health, and listening with an air of concern to the description given him of the various injuries Charlie had suffered, of the shock the accident had been to his nerves, and of how serious the repercussions might be if he were not kept perfectly quiet until such time as dear Dr Foston pronounced him to be well enough to leave his room. Since few things interested her more than the ills that could attack the human body, and was one of those who believed that physical disorders lent distinction to those who fell victims to them, the recital took time in the telling, and was further prolonged by an account of the spasms and palpitations she had herself endured ever since she had seen her son’s battered body borne into the house on a stretcher. “I fell down instantly in a swoon, for I thought him dead!” she said impressively. “Indeed, they thought I was dead, for it was an age before they were able to revive me, and then, you know, I was so much agitated that I couldn’t believe dear Hetta was speaking the truth when she assured me Charlie wasn’t dead, but in a deep concussion. I’ve been very poorly ever since, and Dr Foston has been obliged to give me a cordial, besides valerian for my nerves, which are sadly shattered, as you may suppose.”

He replied suitably; and after expressing his admiration for the wonderful spirit she showed in bearing up under so prostrating an experience, at last ventured to broach his errand to her. He did it very well, but it was no easy task to gain her consent to his proposal. It was rendered all the more difficult when he disclosed that Cherry was Lord Nettlecombe’s granddaughter. She exclaimed at once that she wished to have nothing to do with any member of that family. He replied frankly: “I don’t blame you, ma’am: who does wish to have anything to do with them? But I think your kind heart must be touched by this unfortunate child’s plight! If her father isn’t dead, he has certainly abandoned her—and without a feather to fly with! She has lately been living with some maternal relations, who haven’t used her at all well. So very ill, in fact, that she formed the resolve to claim her grandfather’s protection, until such time as she can find employment in some genteel household. So, as I was staying at Hazelfield at the time, my aunt desired me to carry her to London with me, and see her safely deposited in old Nettlecombe’s charge. You may conceive of my dismay when we arrived in Albemarle Street to find the house shut up, and none of the neighbours able to give me his lordship’s direction! What to do with the girl had me at a stand, until I remembered you, ma’am!”

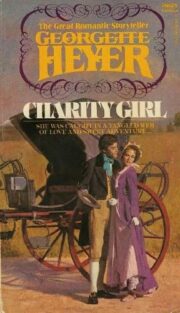

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.